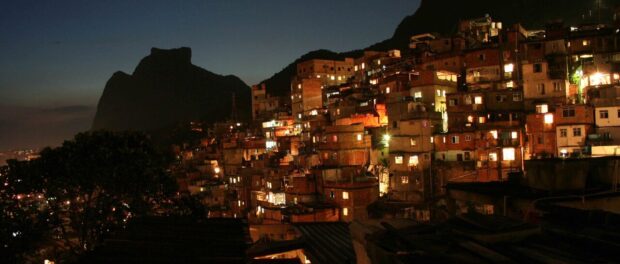

Dan Jackson’s 2016 feature-length film In the Shadow of the Hill humanizes the very real changes imposed on residents of Rocinha as the city prepared to host the 2014 World Cup and 2016 Olympic Games. Amid the portrayals of police abuse, corruption, and forced evictions, the film focuses in particular on the case of Amarildo de Souza, a bricklayer and Rocinha resident who disappeared after being called in for questioning by Pacifying Police Unit (UPP) officers in 2013.

Captured in personal interviews, glimpses of daily life, and action scenes of the fight for justice that followed, Australian director Dan Jackson tells the story of a family and community that is both critical of city policies and hopeful for the future. In the Shadow of the Hill premiered in May 2016 at the Hot Docs: Canadian International Documentary Festival and has since been featured in screenings around the world.

In the Shadow of the Hill has an almost fictional style, with a distinct rise and fall in action between a sweeping introduction and an optimistic conclusion. Before delving into Amarildo’s story, the film contextualizes the Pacifying Police Unit (UPP) program installed in Rio’s favelas in preparation for the city hosting mega-events. When military forces pronounced Rocinha “pacified” following the police operation in November 2011, what followed was not the respect and security associated with true peace. Under the repressive system established, favela residents were subject to violent raids, race and class-based discrimination, and arbitrary arrests.

When Amarildo de Souza disappeared after being called in for questioning in 2013, his family wasn’t given any information or help in finding him. Major Edson Santos, then the UPP commander for Rocinha, denies police culpability and blames Amarildo’s media-alleged criminal connections in a tactic characteristic of the broader criminalization of poverty. The bribery between legislative and executive positions in Rio de Janeiro is also apparent with Major Santos, as he is favored by certain politicians in return for his help on their campaigns. If Major Edson Santos is villainized for playing a key role in attempting to cover up the truth and for perpetuating a corrupt system, then the film holds human rights lawyer João Tancredo in high esteem for his pro-bono support of Amarildo’s case.

Outside of the main narrative of Amarildo’s disappearance and his family’s fight for justice, compelling central characters add great humanity to the film. Aurélio Mesquita, founder and director of the Via Sacra theater group, leads community members in annual recreations of Christ’s journey to the cross while addressing police violence and other pertinent social issues. The plays are portrayed as a form of resistance and empowerment for Rocinha residents.

Meanwhile, when the government forcibly evicts her and her family, Maria Clara dos Santos, the “Mão Santa” of Rocinha, also loses her livelihood of preparing medicinal herbs. Out of economic necessity, she creates the persona of Mulher Maracujá (Passionfruit Lady) and soon gains national attention for her funk-style dancing. Her story is one of entrepreneurial resourcefulness and defying society’s expectations of success for Rocinha residents. She joins the fight for justice for Amarildo by leveraging her fame and skills to produce politicized music.

The protagonists of In the Shadow of the Hill are a group of strong individuals who demand their rights and create a collective movement that transcends race and class. The documentary breaks favela stigmas by showing the creativity, organization, and values of Rocinha residents. Led by Michelle Lacerda, niece of Amarildo and a strong narrator throughout the film, family and community residents refuse to silence their protests despite threats and media slander of the case. Brazilians and foreigners around the world express unity with the virtual campaign asking “Cadê o Amarildo?“ (Where is Amarildo?). International publicity afforded greater security to activist efforts, preventing the government from evading the truth and community demands.

In the Shadow of the Hill covers the alliance formed between the movement for Amarildo and concurrent protests against World Cup spending and government inefficiency at that time. While the latter movement was associated with Rio’s middle class, the groups built solidarity on mutual understanding of the need for a reorganization of priorities by the Brazilian government and an end to state-sponsored violence. Michelle Lacerda remarks that “20 years ago a black favela resident would have deserved their death in the eyes of the public, but not today.”

The film’s closing scenes highlight the unification of these two distinct groups and the power of collective action. Favela residents join hands in protest with middle class Brazilians, chanting and marching toward the governor’s house. The tone is hopeful, united, and spirited. In the Shadow of the Hill gives voice to favela residents who have been traditionally marginalized and continue to face barriers in realizing their full rights as Brazilian citizens. In the end, viewers learn that the protests were successful in holding police accountable; after 25 arrests, earlier in 2016 Major Edson Santos and 12 of his associates were found guilty of the torture and murder of Amarildo. As Michelle Lacerda puts it, “There is justice in this country. It’s slow, complicated and sometimes corrupt. But it exists.”

Upcoming screenings for In the Shadow of the Hill can be found on the film’s website. The film is currently showing as part of the Festival do Rio – Rio International Film Festival.