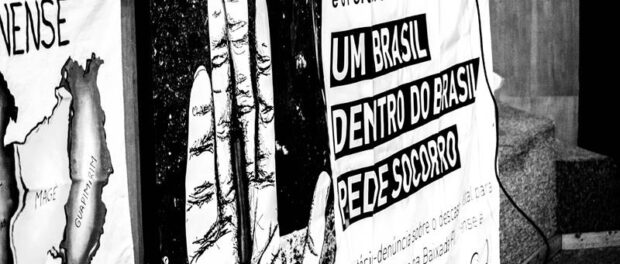

On September 15 at the Rio de Janeiro State Legislative Assembly (Alerj), the Forum Grita Baixada (Scream Baixada Forum), Center for Human Rights at the Diocese of Nova Iguaçu, and other civil society organizations from the Baixada Fluminense suburbs of Greater Rio launched the report “A Brazil within Brazil Calls for Help: Watchdog Report on State Negligence in the Baixada Fluminense and Possible Urgent Solutions,” highlighting the dire human rights situation within the region of 13 municipalities. The report gets its title, “A Brazil within Brazil Calls for Help,” from the immense racial, ethnic, and regional diversity–many Brazilians from the Northeast settled in the area in the 20th century following the abolition of slavery–that exists within the Baixada Fluminense.

However, rather than highlight the extraordinary cultural, historical, and natural wealth of the region, the report notes how the media has perpetuated for decades an image of the Baixada Fluminense as a violent backwater unfit and unsafe for those from Rio’s wealthier central neighborhoods. Journalist Marcelo Auler, who moderated a panel discussion during the launch, attested to the role that tabloids played in selling the Baixada through images of gore and suffering. “I remember when I first started working in journalism in 1974, for Radio Globo, that we had correspondents in hospitals and in the Baixada. One correspondent would call us and say, ‘tomorrow a body is going to appear at this place at this time,’ and the next day there would be a report on the body and headlines about the death squads.”

Violence is indeed a reality in the Baixada. While the city of Rio de Janeiro experienced 18.5 homicides per 100,000 of its 6 million residents, the Baixada, a region of 4 million people, experienced 40 per 100,000. However the report stresses that this violence, both street level and state sanctioned, is ultimately the result of decades of neglect from municipal and State of Rio de Janeiro governments and the past presence of police-affiliated vigilante death squads and the present-day dominance of militia groups. At the launch, Douglas Almeida and Aparecida Pontes of Forum Grita Baixada underscored this pervasive violence by reading out incidences of murders and police massacres in each of the 13 municipalities of the region. The Forum itself was formed after one such act of state violence in which Military Police killed 29 people in Queimados and Nova Iguaçu.

However, rather than just focus on these statistics, the report emphasizes the voices of residents of the Baixada who have suffered human rights abuses including the Pacifying Police Unit takeover of a local school and vote buying on the part of local politicians.

The launch also included poems from two local artists, Coyote and Samuel, that touched on the stigmatization and police killings of poor, black favela residents, poor public investment in favelas and the periphery, and the criminalization of poverty.

The panel discussion moderated by Auler featured Professor João Carlos Dornelles, coordinator of the Human Rights Working Group at the Rio Pontifical Catholic University (PUC), Sister Yolanda Florentino of the Center for Human Rights at the Diocese of Nova Iguaçu, State of Rio de Janeiro Public Defender Dr. Antonio Carlos Oliveira, Federal Fluminense University (UFF) professor and member of Forum Grita Baixada Percival Tavares, and Sociology professor at the Federal Rural University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRRJ) Jose Cláudio Souza Alves, all of whom spoke to the challenges faced by the region, but also the tireless work of civil society in promoting peace and human rights in the Baixada.

“The question of the legitimacy of this report is very important to us,” stated Public Defender Oliveira. “Because in general we have this stereotype of the Baixada Fluminense created and accepted by society, by local, regional, and even national and international society. The Baixada Fluminense has always been a violent place and everyone just accepts this. I was born, raised, and I work in the Baixada Fluminense and I have heard this for as long as I can remember. But here we have the first report on human rights produced by institutions and civil society organizations in the Baixada Fluminense. This is very important because the report has a deep understanding of the causes. These organizations know all of these situations well, and are willing to contribute to the solutions presented in the report.”

The report identifies the lack of a community-oriented public security that “protects life, as opposed to the logic of a war against crime” as the most pressing issue faced by residents of the Baixada. “We, residents of the Baixada, cry out for a greater commitment on the part of the government,” reads the closing letter of the report. “We ask for care for our quality of life, not only in our (necessary but rare) moments of leisure, but, especially, during the hours of the day we spend coming and going to work.”

With municipal elections less than two weeks away, those gathered hoped that the report could spur politicians to seriously address the problems faced by residents, which include not only violence, but poor sanitation, lack of local jobs forcing residents to commute to Rio’s center, and access to quality health care and education.

However, violence has permeated the political process in the Baxiada, with 13 candidates running for local government positions having been assassinated and militia groups pressuring residents to vote for certain candidates. “The details [of the report],” explained Professor Jose Claudio Souza Alves, who has extensively researched militia violence in the region and who himself is running for mayor of Duque de Caxias,”tell us about various operations with the objective of controlling areas, profiting from the areas, and to obtain the most notable gain on the part of these [militia] groups which is political power. This is very evident in the Baixada as a whole.”