The Praça XV square is one of the most important historical locations in Rio de Janeiro. It is located in the historical center, flanked by the Rio de Janeiro State Legislative Assembly (Alerj), the Imperial Palace and the city’s ferry terminal. Only people with a profound knowledge of history know why Rio’s stock market building is here as well. Before goods, people were traded here. There is no sign, plaque, or memorial that indicates this used to be one of the earliest slave markets in modern history.

Between the 16th and the 19th century, more than 5.5 million enslaved Africans were brought to Brazil, and more than 2 million disembarked in Rio alone. In contrast, some 400,000 arrived in all of the United States.

Today, Brazil is the country with the second largest black population in the world after Nigeria. Half of its population is black. It is a country that has lived less than a quarter of its history without slavery.

The ongoing impacts of slavery on economic and social structures are far more visible than the public references in Rio’s urban landscape. Black Brazilians make up the vast majority of construction workers, maids and nannies. Rio’s wealthiest neighborhood Lagoa is only 1.5% black while the city’s favelas are majority black, as is well described in this series of racial maps.

Historian Sadakne Baroudi asserts: “500 years after the introduction of slavery in Brazil, black people are still building our cities. Cities they are systematically excluded from.” Baroudi started researching slavery in Rio over a decade ago and launched an educational bilingual website about the history of slavery in Rio’s Port.

When Baroudi first came to Brazil in 2003, the racism she experienced felt almost like the prejudice she was used to in the US. Except that here, no one talked about it. One of the common national myths is that because of the huge variety of skin colors in Brazil, there is a “racial democracy” in which racial discrimination is considered irrelevant.

The national narrative is that discrimination ended with the abolition of slavery in 1890. In contrast to the US with its strict discrimination policies–the Jim Crow laws–and open race riots, race is constantly negotiated in Brazil. “Someone is just darker or lighter than the person next to him, so everyone gets pushed in the middle. There is not a sharp distinction between black and white like in the United States,” says Baroudi. “In Brazil people are proud when they tell me, ‘at least we never made anyone sit in the back of a bus.’ The thing is: they are not even in the same bus. The transportation system is still segregating people.”

Another cornerstone of Rio de Janeiro’s urban identity is its history as former capital of both Brazil and the Portuguese Empire. The city is proud of its European inspired boulevards, of being a “Tropical Paris.” And it is also a city in love with modernity, progress and transformation, made mainly at the cost of its black citizens. During the last century major urban transformations in Rio meant majority black communities were regularly displaced: the removal of the Castelo Hill for the redevelopment of downtown Rio in the 1920s; the removal of Praça Onze for the construction of Presidente Vargas Avenue in the 1940s; the metro construction in the 1970s; and most recently the 2016 Olympics for which around 77,000 residents lost their homes.

Olympic construction works not only shaped the further racial segregation of the city, they also revealed something of the past. Drainage works carried out as part of the Porto Maravilha project in 2011 uncovered the Valongo Wharf, Rio’s main slave market after the Marquis do Lavradio, Viceroy of Brazil, was too horrified by what he saw from his Palace at Praça XV. For more than a century and a half, the place was more or less forgotten. “I believe they buried it to eliminate the evidence of slavery,” says Washington Fajardo, president of the city’s World Heritage Institute.

At the Valongo, slaves could be bought individually, or by weight: for example, a buyer could either purchase one healthy man at a high fixed price or bid on 100kg and get a combination of people available in poorer shape, like some children, a pregnant woman, or injured people. The site also had “fattening houses” and mass graves where those who hadn’t survived were thrown or those who wouldn’t survive were left to die.

Nothing can be seen or read about this history at the newly recovered archaeological site. There is a sticker on a piece of cardboard with some basic facts and a map of the African Heritage Circuit around which visitors can explore the African influences in the Port area. But the region does not attract a large number of visitors and the Valongo often feels like an abandoned construction site.

The nearby slave cemetery run by a small privately initiated institution is even harder to find. In renovating their home in 1996, Merced and Petrucio Guimarães uncovered human bones. When they discovered that these bones belong to more than 20,000 bodies, a lot of them children and teenagers, buried underneath their new home, they felt the obligation to open a public memorial space, the New Blacks Institute and Cemetery (IPN by the Portuguese acronym). As part of the Porto Maravilha project, IPN received a little funding, but Merced is afraid that under newly elected Mayor Marcelo Crivella this will come to an end and the Institute will struggle to continue its work.

The other museum dedicated to the preservation of black history in Rio is funded by a much wealthier organization, but is still not in very good shape. Run by the Catholic Church, the small Black Museum is located in the back of Our Lady of the Rosary and Saint Benedict Church in downtown Rio de Janeiro. The entrance is difficult to find. The inconspicuous sign–“Black Museum, founded in 1969”–is in fact at the opposite site of the actual entrance, where nothing points to the existence of a museum. After walking through the church assembly hall, you have to turn on the lights by yourself.

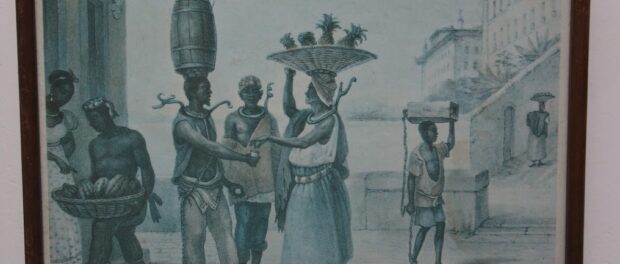

In the entrance there is an antique illustration of slaves in Brazil: a pleasant market scene with a slave carrying a stone attached to his ankle, another one with a barrel of water on his head and a woman with a basket of pineapples. The iron collars around their necks have decorative ornaments and look like African necklaces.

The picture is by French painter Jean-Baptiste Debret (1768-1848). His lithographs are among the most important graphic documentation of daily Brazilian life in the early decades of the 19th century. They appear frequently in school books. In his paintings, slavery looks like an exotic episode in Brazil’s ancient history, far from representing the brutal reality of this dark chapter.

The almost romanticization of slavery in Brazil is not uncommon. There is the attitude that Brazil employed “escravidão suave,” or “soft slavery,” the myth being that the Portuguese were too laid back to run an efficient slave system. Today the basic idea that slavery was in fact brutal is still contested. In the Black Museum there are no tags, no signs and no explanations of the displayed objects. Also, the role of the Church during slavery was complicated. With this institution running the museum, Baroudi questions: “Who controls the narrative?”

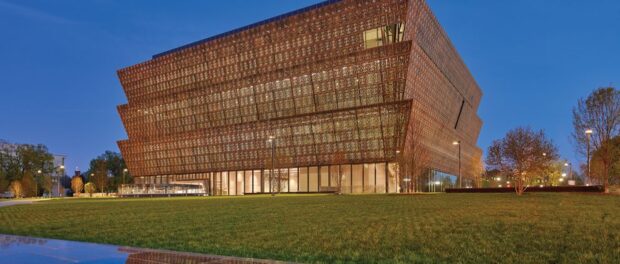

Successful black history museums can be found outside Rio, such as São Paulo’s Museu Afro Brasil, or the recently launched and celebrated National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington D.C. The 400,000-square-foot museum is next to the Washington Monument on the Washington Mall, near the most famous museums in the US capital. The building is “bronze and brooding,” in the words of architect David Adjaye, “floating in a sea of white marble and limestone [the other museums].” And museums established to inspire reflection and a coming to terms with dark periods in their nation’s history, such as Santiago’s Human Rights Memorial Museum, are a growing and important phenomenon. But these outstanding museums are not dedicated to preserving and reflecting on the legacy of slavery; rather, they are dedicated to the history and culture of Africans in the Americas in general, or other human rights themes. In fact, despite its tremendous scale and impact worldwide, the world is practically devoid of museums reflecting on slavery.

Rio’s Port Region, where millions of enslaved Africans disembarked, has gained two new world class museums in recent years. The R$185 million Museum of Rio Art (MAR) was inaugurated in 2013. The R$250 million Museum of Tomorrow opened earlier this year in time for the Olympic Games. Yet the history of the region and its significance to Brazil–and the world’s–slave trade remains unrecognized in this dramatically redeveloped space.

This institutional erasing of the Port’s past and continued lack of a museum memorializing slavery has angered many black Brazilians and historians. Ronilso Pacheco, representative of the NGO Viva Rio and member of the Coletivo Nuvem Negra (Black Cloud Collective), a black student group at PUC-Rio, writes: “It disturbs my own history, and my historical consciousness, to know that a black past is deliberately ignored and destroyed so that a white middle class future can be erected in its place with celebration and pageantry. Could anyone imagine building a Museum of Tomorrow at Auschwitz? Never.”

History teacher and Rio politician Marcelo Freixo, who ran for mayor last month, is one of the few official voices to express this view, saying: “Nothing against the Museum of Tomorrow, but what about our past? The Port Region was an entry point for slaves, but the whole black past is in a container box. Berlin has a museum about the Holocaust, why isn’t a slavery museum in the Port Region?”

The question merits serious consideration and discussion among Rio’s governments, academics and civil society. For the city to move towards a just future, it must reckon with, confront and appropriately recognize its brutal past.