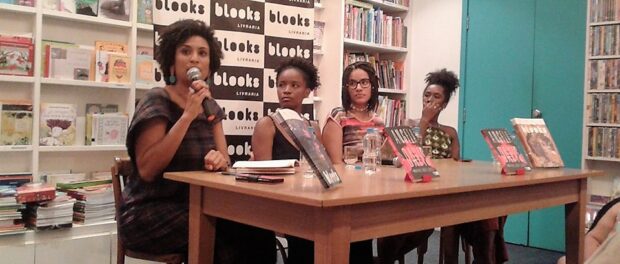

As part of a circuit of events celebrating Black Awareness Month, the book Women, Race and Class by American intellectual and feminist Angela Davis was launched at Livraria Blooks in Rio de Janeiro on November 10. The launch of the book in Portuguese, 35 years after its original publication, marks an important moment of recognition in Brazil of the nexus between race and class issues, combined with feminism, but also beyond it. The launch served as a backdrop for a discussion about being black, being a woman and living in a favela in Brazil. The debate panel was made up of journalist, activist and Complexo da Maré resident Ana Paula Lisboa, historian Jaciana Melquiades and sociologist Karina Vieira, both activists with the Meninas Black Power collective, and mediated by elected city councillor and Maré resident Marielle Franco.

The importance of launching this book now is to make yet another instrument of struggle and empowerment of black resistance accessible, especially in a white, academic setting. “The biggest contribution that Angela brings to us at this moment is getting us out of being an object of study and placing us as researchers. I had difficulty legitimizing my academic writing with a 90% black bibliography to a committee of Masters and Ph.D.s who could not evaluate my dissertation because they did not know of Sueli Carneiro,” Karina said. And she went further in acknowledging the importance of the book’s translation at this time: “There was no Angela Davis in my bibliography because I do not speak English.” Ana Paula added: “When I got the book, I posted a photo on Facebook and an American friend of mine commented that she had read this book when she was 12 years old. I was a bit frustrated, but I was happy because now 12 year old girls will be able to read Angela Davis (in Brazil).”

The importance of launching this book now is to make yet another instrument of struggle and empowerment of black resistance accessible, especially in a white, academic setting. “The biggest contribution that Angela brings to us at this moment is getting us out of being an object of study and placing us as researchers. I had difficulty legitimizing my academic writing with a 90% black bibliography to a committee of Masters and Ph.D.s who could not evaluate my dissertation because they did not know of Sueli Carneiro,” Karina said. And she went further in acknowledging the importance of the book’s translation at this time: “There was no Angela Davis in my bibliography because I do not speak English.” Ana Paula added: “When I got the book, I posted a photo on Facebook and an American friend of mine commented that she had read this book when she was 12 years old. I was a bit frustrated, but I was happy because now 12 year old girls will be able to read Angela Davis (in Brazil).”

The audience, made up mostly of black women and men, occupying a space–both physically and academically–that is traditionally white, of a bookstore on Praia de Botafogo, was impressive and cause for celebration. “But at the same time it is a critique that I have of any gender movement that is always speaking to the same people. Because talking to them does not change much. That’s why I didn’t hesitate to accept the invitation to write in O Globo because I wanted to speak to other people, since its traditional readers are not my people. Racism has to be everyone’s struggle. As long as it is not everyone’s, we will continue reproducing racism,” said Ana Paula, who recently began publishing a fortnightly column on Wednesdays in the newspaper O Globo. Alessandra, who was in the audience, praised the event and reinforced that “It’s always good for us to do black things. But to do them in the South Zone, in a bookstore, is even better.”

This intersection of race, class, and feminism was a recurring theme of debate during the night. Jaciana began her speech by stating that she was not a feminist woman. “I do not identify myself within this way of thinking. I’m a black woman who wants to be in the world as a black woman.” Marcelle Decothé, an Amnesty International activist, spoke from the audience: “Angela debates the relationship between class and race. Capitalism is a system designed to imprison us in the class that we are in. The system is made for us to be cheap labor. We went from slave to cheap labor. Then people say that we die because we are poor, not because we are black.”

Davis also recalls the historical bias of the women’s liberation movement in her book. “But the black woman has always been historically excluded. First comes the white man, then the white woman, then the black man, and then the black woman. In these two cases of class and gender, it is necessary to racialize the debate, because racism is present in all subjects,” said Marcelle. Karina agreed with her on the importance of bringing race into all debates: “I’d rather decolonize the stories and racialize the debate. For me, race comes first rather than gender or class.” For them, this ensures that black collectiveness does not split into different factions and thus weaken itself: “The key word is self-care. It means to know ourselves, to recognize ourselves as a powerful people, to surround ourselves with our own people,” said Karina.

“For me to get here today, I endured racism. For me to rent the apartment where I live, I endured racism. For me to pick up my son who studies in a public school, I, a black woman, with my black son in a public school shirt, endure racism. The driver was rude to me today for the simple fact that I was a black woman. I do not look like someone who lives on the street. So it’s not about class, it’s not about money, it’s about the color of my skin,” echoed Jaciana. “We black women are often accused of being aggressive in our claims. But we’re not the ones who are aggressive, it is racism that is aggressive, that whips us daily. So sometimes there’s no sweetness in my speech because I’m sick of it,” Jaciana said.

An issue raised several times in the audience’s questions was what to do to combat racism and how to overcome the existing bridges between blacks and non-blacks in this struggle. There is, in fact, no right answer and it is an issue that divides opinions. For Jaciana, you do not have to be black to fight against racism: “You can fight for the same thing, but not necessarily on the same battlefields. White people, in their white universes, can make the world more colorful. Because they’re the ones who hire employees. They are the ones who can choose to hire a black person. If you are the boss, ask why there are only white people occupying this environment. We do not have to be here talking about Angela Davis to talk about racism. We can talk about racism in all spaces.” Karina added: “We need to deconstruct privilege. Rise up. If someone gives you a job, say so if there’s a black person who does it better than you. Another thing that can be done is in the field of language. Terms like mulato, pardo, and moreninho are not suitable anymore.”

Jaciana associated the use of the term “pardo,” which can mean brown or mixed race, with a historical erasure. “When I say that a person is pardo, I am denying them the opportunity to know their black history, I am alienating them from their black history. We talk to white people who can say the name of the ship on which the family lineage came to Brazil. We can understand your family tree. Black families have no history. I cannot say what ship my family came on. If I know that I am a black person, that I came on a ship, that I have a history, a past, I am a descendant of kings and queens, of people who had attended universities.” Jaciana works with children and reports their frequent surprise at this information: “‘Is Africa not a country?’ They ask. All the black history that children know is the story of slavery. That black people made drums and got beaten.” Karina added: “They need to understand that we do not talk about blackness from racism or slavery. We have a history before that.”

For Jaciana, the emancipation of the black body is going through a referential change. “I want to be a black woman and I want to be able to think about the references that make sense to me. This week my son saw a rainbow and said that Oxumarê had sent him a gift. Nobody understood anything, because the rainbow comes from the gnomes, but his reference is an orixá. It is through another framework, that of emancipation, of seeing a black person with a past, with a history, of people who resemble him, that makes him create positive identities,” she said. So, according to her, he will recognize the origin of the problem of racism in the person who is racist, not in him or herself for not conforming to certain ideals: “From this emancipation framework, my son will understand that any place in the world is a place for him.”

Karina added: “It’s not just the price that makes a young black favela resident not frequent a space. It’s because the space is racist. And how do we dispute this space? Through education. We get into university and have to go back to our places, not with a look of arrogance towards our own people. It’s looking back and saying, ‘Wow, we still have a job to do. Let’s do it.’ If I can not ‘favelize’ spaces, there is no emancipation.”

Another issue that arose, especially when it comes to blackness and women, was that of black aesthetics. Jaciana said she only discovered that she was black and beautiful at age 28. “How do we make adults recognize themselves as people? We will only come to this answer through education. And not through a failed education that is a political project for us to continue in subordination. Not this education, but the education that we practice, guerrilla-style,” alluding to the social projects in which she participates. “We do not accept it anymore. This is what we say every time we take the bus with money from our pocket to go to a school there in the Baixada. We go and tell our history to the children so they can look in the mirror and understand that they are people.”

“They always classify us as a beautiful black girl. If we do this with a white person it causes discomfort. ‘How so? I am a person.’ We are all people, but there is beauty and black beauty”, said Jaciana. In Karina’s opinion, in addition to the recognition of black aesthetics, one seeks recognition as a black being. “We are more than big hair and colorful lipstick. And while we are discussing this, there were the 19 deaths in São Paulo, 12 in the Cabula, five in Costa Barros.” This violence is reflected in the personal story of Ana Paula, who lost her brother to arbitrary police violence: “I am one of the women who remains.”

“Now let’s be concise because it’s late and we all have to take buses and the metro,” proposed Marielle to close the debate, highlighting the challenge of urban mobility in Rio de Janeiro, especially in the peripheral areas. “We leave better and stronger than when we got here. It’s important to be together. A blackness that not only decolonizes spaces but occupies spaces.” For Marielle, to take over a space of decision in politics is a form of emancipation, as well as to take over a space of representation, as Ana Paula does in O Globo. Marielle concluded by saying: “From where I’m speaking, I hope that we can build together, from occupying a space of representation of a black woman that I occupy. We’re going to blacken the City Council, racialize the debate, hire black and favela cabinet chiefs. I did nothing in my life alone, everything was done in the collective and this is how I will continue getting things done.”