As of December, titling of favelas and other communities on federal land initially occupied without permission across Brazil may have become much easier.

Interim Measure 759/2016 was published on December 23, 2016, to facilitate regularization of both urban and rural federal land across Brazil. Interim Measures, or Medidas Provisórias, are acts solely by the president and come into force immediately, similar to Executive Orders in US law. Notably, in addition to facilitating land regularization and encouraging individuals on federal land to seek legal title, MP 759/2016 also recognized the direito a laje, a common investment asset in favelas–referring to the ownership of the right to build an additional story on top of the building in question.

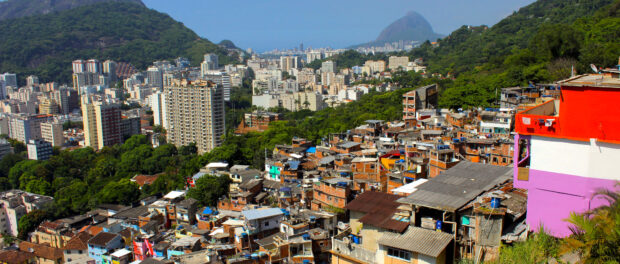

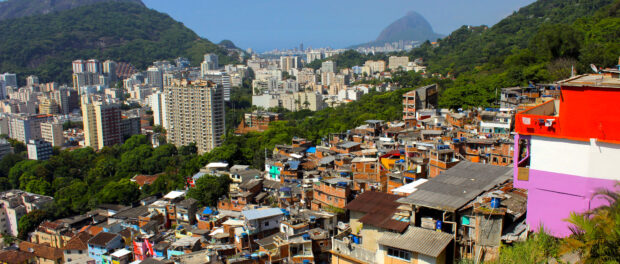

Chapter IV covers the direito a laje which is a newly recognized property law right in the Brazilian civil code. Laje, literally “slab,” refers to the pre-prepared cement slab roof on a house that is left robust enough to withstand additional stories built above. Favela homes will be “with laje” or without, and this indicates whether or not it is ready to take on additional floors. A related but different concept (and seen as illegal) are puxadinhos, or additions to existing buildings that extend them into the public realm (of the street, for example). Both the laje and the puxadinho are strategies employed by favela residents to meet the need for space of growing families and community businesses.

MP 759/2016 regularizes the practice of recognizing ownership of the laje by providing that they can be recognized as separate units with a separate owner and a legal title distinct from the rest of the building. Article 25, subsection 7, clarifies that pre-existing laws that allowed for separate ownership of the same building applied only to condominiums. Although a similar concept, the laje was not regulated by the condominium laws, and before MP 759/2016, the laje could not be owned separately.

A laje may be a floor of a building, basement, or other unit. To qualify legally as a laje under MP 759/2016, Article 25, the unit must have its own entrance and it must be impossible to divide the land on which the building sits into individual lots. Article 25, subsection 5 also provides that lajes are “alienable:” those with title to a laje will be able to sell the unit and record the sale, or other legal changes to ownership.

To facilitate regularization, the law includes measures to ease acquisition of legal title. The traditional title will be replaced with an “acknowledgement of original acquisition” once the registration system is approved. In order for this registration to be carried out, municipal governments are told to recognize occupations of both public and private land as irreversible and consolidated.

Chapter 1, section II, provides two routes to regularization: social interest and specific interest. Social interest refers to low-income individuals who occupy the land for housing. For those who fall into this category, the government covers the costs of registering the property and all basic infrastructure for the property. Those who do not fall into the first category may regularize property under the specific interest provisions, but will have to cover their own costs.

Proponents of the law argue that regularization will bring millions of property assets into the economy, helping to stimulate the market. Additionally, they promote that formal land ownership increases access to credit. Meanwhile, social movements fighting for land reform in Brazil are skeptical of the intentions and concerned about the potential impact of the policy. Brazil’s Landless Workers Movement (MST) says the objective of this titling scheme is simply to “put land on the market” and “turn Brazil’s land regularization agency (INCRA) into a real estate developer.”

In cities, skeptics worry that regularization with individual titles will fuel real estate speculation and make favelas vulnerable to gentrification, ultimately pushing low-income residents to the city’s outskirts to form new, precarious favelas. In fact, several favelas in Rio are already witnessing residents rejecting titles for this very reason. Furthermore, land regularization does not address primary problems faced by favela residents, such as a lack of access to basic services like sanitation, quality education and healthcare.