On December 13, the Brazilian legislative branch passed PEC 241/55, a constitutional amendment that puts a cap on all federal spending measures for the next 20 years, and only allows for reassessment of the amendment after the 10-year mark. The provision allows for inflation but no other possible influencing factors such as demographic or political changes, or population growth.

PEC 55 (originally PEC 241) has gotten mixed reviews from Brazilian and international communities since passing. UN special rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights, Philip Alston, expressed his deep concern and says the bill violates Brazil’s obligations under the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. “This is a radical measure, lacking in all nuance and compassion,” said Alston. “It is completely inappropriate to freeze only social expenditure and to tie the hands of all future governments for another two decades.”

Meanwhile, in the government, the Secretary of Economic Monitoring, Mansueto Almeida, claims that education and health will remain a priority and that “spending on education will abide by the constitutional rule that determines that 18% of all taxes must be spent on education. For the coming years the amount to be spent on education must be adjusted according to inflation rates.” However, opponents like Pedro Paulo Zahluth Bastos from the University of Campinas, do not see adjustment for inflation as sufficient enough to prevent dips in social investment, and predict that even with inflation taken into account, education spending per child will fall by almost a third.

The topic of education spending has been a contentious one since the mid 1990s. While today in Brazil a high school education is obligatory, and policies have made enrolling children easier on low-income families (such as via the conditional cash transfer program Bolsa Família, which requires low-income mothers to enroll children in school in order to access supports), little has been done in terms of structural improvements or long-term investment in the quality of education.

In March 2016, teacher and student-led strikes took on full force. State-run public school employees had not seen an increase in wages since 2014, even during a period of inflation and a severe economic downturn. The SEPE (State Education Professionals Union), a state-wide teacher’s union, paved the way for teachers and administrators to join forces in the resistance, while students expressed their own dissatisfaction in leading the school occupation movement. On top of this, the state of Rio de Janeiro entered a financial crisis, and salary payments were made later than promised.

Dorotéa Frota Santana, SEPE coordinator and long-time public school teacher in the City of God favela, says that in terms of education, “this year will be awful. The devaluing of teachers, lack of investment, and freezing of salaries is a total regression for public education. What is happening with education is very bad.” Though strikes slowed towards the end of 2016, there is nothing preventing them from picking back up again now with the 2017 school year approaching and the newly passed PEC 55. With schools in Rio de Janeiro already lacking investment and attention, it seems counterproductive to enact such harsh national legislation that ignores gleaming social realities. And while Santana is not certain that another strike will take place in the near future, she says “it all depends. People are very worried about the lack of salaries. I defend it. We just have to do a temperature check and see how other employees feel.”

In Rio de Janeiro, 51.6% of students do not graduate on time, largely due to repeated school years. And while attendance is mandatory from kindergarten through graduation, school days last only three to four hours mostly due to limited resources and the overcrowding that results. Even with split morning/afternoon classes, teachers are still often left with 45-70 students per classroom. Some schools, she says, have even been abandoned. “The most pressing concerns are the stressful working conditions, overcrowded classrooms, lack of material, and run down infrastructure. Now, after months of complaints, the state is finally starting to make repairs.”

Inadequate public schools ultimately lead to stark socio-economic disparities across the city. In the South Zone and Barra da Tijuca neighborhoods of Rio de Janeiro, the areas with the highest medium income, the illiteracy rate for 8 to 9-year-olds is 6.3%. However, in neighborhoods like Santa Cruz and Ramos, areas with considerably lower income levels, the child illiteracy rates are as high as 9.5% and 8.7%, respectively. When comparing public versus private schools in Rio de Janeiro, the child illiteracy rate for students enrolled in public schools was 8.3%, but only 1.1% among children of the same age enrolled in private schools.

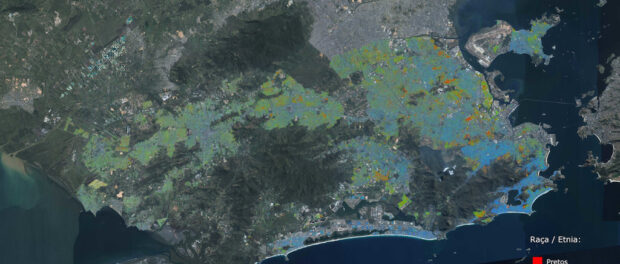

Glaring deficits in education quality reflect racial inequalities as well. In every single age group, black students have a higher illiteracy rate than white students. For example, in the 15+ age group, the illiteracy rate among black students is 4%, while among white students in the same age group, the illiteracy rate is a mere 1.8%. And as can be seen in the map below, the neighborhoods with higher literacy rates cited above are also those dominated by white families (the South Zone and Barra da Tijuca), while those with higher relative illiteracy rates are those home to a greater percentage of black families.

For the 2017 school year, improvements in education in Rio de Janeiro seem all but likely. Municipal and state-run public schools are already struggling. Spending and investment would have to increase dramatically to meet the growing demands of students, teachers, and administrators, and PEC 55 has done away with this possibility. Unfortunately, those in already marginalized communities will be hit the hardest by such extreme economic measures.