In the favela where I live, the government spends thousands of reais for the Military Police to come in with war tanks and heavy weaponry. Who cares if stray bullets kill innocent people?

At my university, the dean wants the semester to last just two months due to lack of funding. Who cares if students learn anything?

Welcome to post-Olympics Rio de Janeiro.

I study at the Rio de Janeiro State University (UERJ). It’s the fifth best public university in Brazil and has more than 30,000 students. Last year, UERJ began being affected by spending cuts made to finance the Olympics: the academic year started after five months without classes and our semester ended with many classes canceled due to protests.

Rio de Janeiro’s state government declared bankruptcy at the end of last year. This meant the necessary funding for UERJ’s maintenance and payment for university workers wasn’t transferred. Students haven’t received scholarships, professors and contracted staff haven’t been paid and problems with cleaning, security and elevators have worsened.

At the beginning of this year, after an unresolved conflict between the state governor and university dean’s office, there was no surprise when term time approached and we learned that UERJ would grind to a halt once again. First, the dean’s office announced that classes would be postponed for one week. Then they were postponed for two more. Each week the length of time before classes were expected to return was extended.

A solution emerged one month later: the governor would privatize the state water utility CEDAE, thus providing a loan guarantee to pay off debts with the public sector and allowing UERJ to resume classes.

A month after the privatization was approved by the State Legislative Assembly (ALERJ), however, the dean’s office still hadn’t announced anything about the start of the semester. Tired of waiting, some of my university friends started new jobs, others went on vacation, others requested a transfer to a private university where they’d have to start again and pay a monthly fee but at least they’d have an expected graduation date.

After five months of strike, a further three months of the dean’s office postponing classes and a month after the privatization of CEDAE, we unexpectedly received notice one Thursday that classes would resume the following Monday.

What about the students that had already started working? Miss a semester or quit their new job? And those that planned to go on vacation, or to start at another university? Miss a semester or lose the money they’d invested?

The worst part is not knowing if the semester will really start: visiting campus this week I was confronted with the same structural problems.

The stipend payments are still delayed and the university restaurant where you can get cheap meals is closed. The issue of professors’ and other staff’s wages remains unresolved. In terms of contracted services, the bathrooms and elevators still need repair and maintenance.

I was inside UERJ, but it was another UERJ, comprised of students who have the privilege of attending classes despite the resource crisis, who don’t depend on financial assistance.

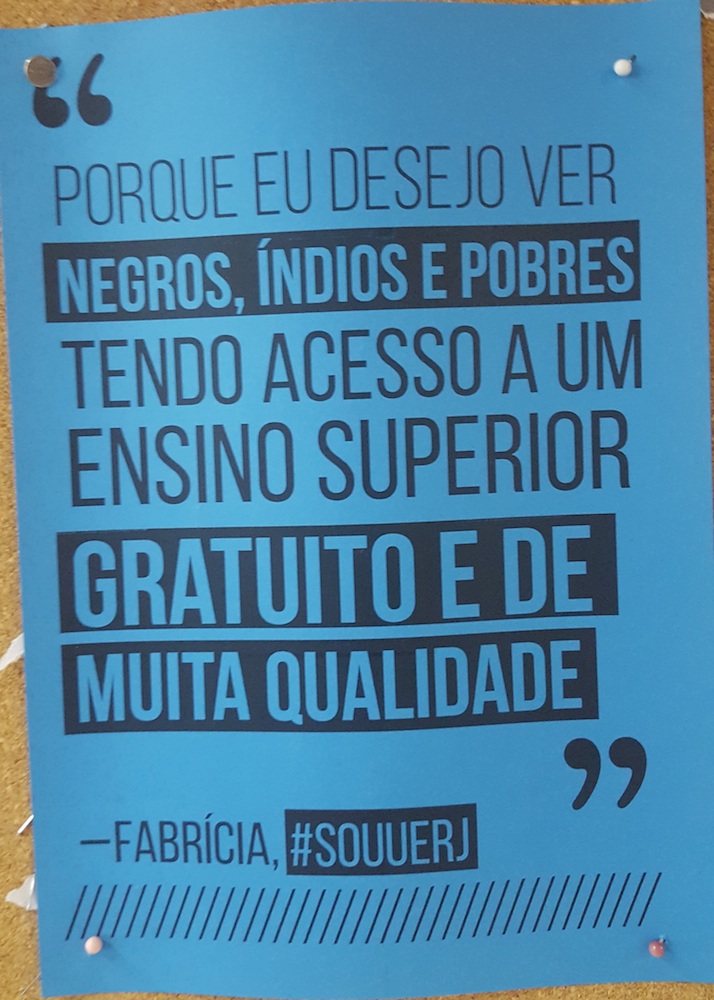

Our university was the first institution in Brazil to implement affirmative action. I’m not ashamed to say that I got into UERJ through this system. I’m proud to be the second person in my family, after my brother, to go to university despite studying in Rio’s inadequate public school system and having various difficulties at home.

Nonetheless, with this forced return to school it is us, affirmative action students, who are being excluded from the right to education. Without our scholarships and with transport subsidies canceled, we’re being denied our right to attend class.

Faced with this situation, I went home extremely frustrated: in what country, at what university is a student informed out of nowhere that the semester will begin in four days time? What about his or her plans, or job? In what country, at what university are classes only open to those students who don’t depend on financial assistance (which is delayed and remains so)? In what country, at what university does the dean’s office allow an institution to operate when it is totally without resources for maintenance or staff wages?

On Tuesday night I got my answer on seeing the university calendar released by the dean’s office: in seven months we’ll have three semesters of two months each with a little time off in between. It’s as if our university has become a supplementary education center where all you need to do is learn the basics, memorize facts and pass the exam.

A university that follows this route doesn’t create intellectuals or produce knowledge. All it does is issue diplomas.

I now realize that none of this has anything to do with my education and never has: it’s about political negotiations between the dean’s office and the governor, the money lost on the Olympics, and how Rio de Janeiro and Brazil can improve their image in the media after so many problems in all spheres of society.

And so I remembered where I live: in post-Olympics Rio de Janeiro, where the police are financed to implement a policy which keeps killing my neighbors, where politicians have money to give to their friends in the form of work contracts and cabinet positions, and where the university doesn’t have resources for education.

Aline Galdino is a university student. She studies Computer Science at UERJ and lives in Complexo da Maré.