In Brazil, 52.5% of the population has a Facebook profile, making it the third highest user base in the world. And favelas are at the heart of the country’s social media craze. 59% of favela residents use the Internet, higher than the 54% of residents of the formal city who use the Web, according to a 2015 study by the Favela Data Institute. In Rio, 90% of favela youth access the Internet regularly, despite their communities being some of the last parts of the city to receive formal telecommunications systems—par for the course in a pattern of favela exclusion from technological infrastructure and social services. However, the mass availability of smartphones and 4G data coverage has allowed many to access the Internet without a computer.

A presence on the Internet and social media gives stigmatized favelas the power to represent themselves. This has been particularly important given the negative stereotypes and political biases common in Brazil’s monopolistic media landscape.

Now, favela residents are leading the way in using Facebook to fight the interwoven practices of real estate speculation and government-sponsored eviction, which have threatened favelas on a cyclical basis since they began to form 120 years ago. Rio is seeing vibrant solidarity between favelas resisting forced eviction through a variety of community-based Facebook pages and groups. The social network opens new possibilities for their organizing, protests, and community-building. Let’s take a look at five ways favela activists use Facebook in their fight against eviction.

1. Creating Visibility For Residents’ (Counter) Narratives

Justifications for forced eviction in Rio are many and varied. Former Rio Mayor Eduardo Paes used the Olympics spectacle to explain the “necessity” of the near-total destruction of the West Zone favela of Vila Autódromo. In the South Zone, Horto residents have been falsely labelled “invaders” to justify the Botanical Gardens‘ eviction plans. Favela activists turn to Facebook to disrupt the official story by telling their own. In the process, they attract allies to their struggle and hold the powerful accountable.

Vila Autódromo activists were particularly adept at this during their multi-year struggle against eviction leading up to the 2016 Olympic Games. Posted on the Vila Autódromo page just five months before the Olympics, this video update (below) by resident and activist Sandra Maria informs viewers of the city government’s increasingly aggressive demolition efforts. “We are making this video today to try to explain all that has happened here at Vila Autódromo these past two weeks,” begins Sandra Maria. She explains how the City’s repeated and irregular eviction notices had complicated the Public Defenders Office’s work on behalf of the community and created an atmosphere of dread. By sharing these experiences and emotions, residents publicly testified to the deteriorating physical and psychological living conditions that forced many of their neighbors to negotiate with the City, undermining the mayor’s claim that a majority of former residents actively wanted to leave.

Smaller groups of favela residents, like the fewer than 20 families of Maracajás Road on Ilha do Governador, relied on Facebook to publicize an eviction threat that would otherwise never appear in the mainstream media. The Aeronáutica, a branch of the Brazilian Air Force, is trying to claim the families’ land and has ordered residents to destroy their own homes and leave. Their brand new page, SOS Maracajás, has almost 300 followers who attend protests and offer support. One of the first posts (below) explains: “Our home, for example, is more than 93 years old, the age of my grandmother, who married and went to live in the house… Before the Aeronáutica arrived on Ilha do Governador, my grandmother lived in this house. However, they came claiming possession of the place, saying our residence is illegal and that we invaded land belonging to them.” Having a space to share their own history is critical for residents. Brazilian media giant O Globo’s coverage of a Maracajás protest included no resident perspectives, instead focusing only on how they disrupted traffic.

The residents of Horto have used their page Horto Fica (Horto Stays) to re-craft the slanderous narrative that they are “invaders,” spread by Globo and Botanical Gardens president Sérgio Besserman. In fact, Horto residents were among the founding employees of the Gardens and were encouraged by its administration to settle on the land next to it. Followed by 1,365 people, the Horto Fica page features a pinned post that sets the record straight. “UNDERSTAND THE CASE IN DETAIL” it reads, breaking down the community’s history and telling a counter-narrative: “We are facing a brutal attempt at the gentrification of our neighborhood in favor of real estate speculation!” The page offers evidence of the residents’ rights to their homes in the form of oral testimonies from older residents produced by the Horto Museum (below). Through it, Horto publicly tells its own history and disproves the invasion narrative. A petition shared on the platform demanding an end to evictions has over 3,500 signatures, but the struggle continues.

2. Documenting and Archiving the Struggle

Facebook is a massive depository of information. Its system handles more than 500 terabytes of data and 2.5 billion pieces of content every day. Favela activists have taken advantage of the ease of creating and sharing information on the platform to make their pages a sort of archive of resistance.

When Current Mayor Marcelo Crivella unveiled his Strategic Plan for municipal management in July, he targeted the sprawling West Zone favela of Rio das Pedras to receive “verticalization”—high rise apartments on the site of current residents’ homes. Fearing evictions and drastic changes to the community, a commission of residents formed to resist the plan. With the #RioDasPedrasContraCrivella (#RioDasPedrasAgainstCrivella) Facebook group, which has grown to over 22,000 members in a few short months, they pioneered the practice of using Facebook’s live-streaming video feature at every one of their events. Scrolling through the group, smartphone video and texts reveal the progressive development of their struggle through meetings with other communities facing eviction, community clean-up work days, protests, and statements from organizers.

When Current Mayor Marcelo Crivella unveiled his Strategic Plan for municipal management in July, he targeted the sprawling West Zone favela of Rio das Pedras to receive “verticalization”—high rise apartments on the site of current residents’ homes. Fearing evictions and drastic changes to the community, a commission of residents formed to resist the plan. With the #RioDasPedrasContraCrivella (#RioDasPedrasAgainstCrivella) Facebook group, which has grown to over 22,000 members in a few short months, they pioneered the practice of using Facebook’s live-streaming video feature at every one of their events. Scrolling through the group, smartphone video and texts reveal the progressive development of their struggle through meetings with other communities facing eviction, community clean-up work days, protests, and statements from organizers.

Andreia Ferreira, who started the Facebook group, told RioOnWatch, “The Mayor and his advisers counted on the ignorance of the people from the community to be able to deceive them. We, through the Internet… were able to bring information to the people. [Crivella’s plan] would have been easy [to implement] if it weren’t for this work of awareness-raising through the Internet.”

Andreia Ferreira, who started the Facebook group, told RioOnWatch, “The Mayor and his advisers counted on the ignorance of the people from the community to be able to deceive them. We, through the Internet… were able to bring information to the people. [Crivella’s plan] would have been easy [to implement] if it weren’t for this work of awareness-raising through the Internet.”

Last month, members of the Rio das Pedras commission recorded Mayor Crivella’s representative Paulo Santos Messina telling hundreds of residents that the city government’s plan had changed, stating “there will be no evictions.” No major media outlets released this video or the quote the next day. But the milestone was documented on the Facebook group (and here on RioOnWatch), allowing residents to hold Crivella accountable as he revises his upgrading plan for the neighborhood.

The small community of Barrinha in Barra da Tijuca seems to be replicating the Rio das Pedras model with their own Facebook group, #ficabarrinha. The 51 families living there recently received an eviction notice, which they believe is motivated by various private interests supported by Mayor Crivella. Posts in their group have documented the residents learning from other favelas like Vila Autódromo, hosting meetings aimed at supporting women in their struggle, and attending anti-evictions protests (below). These posts provide evidence of the work Barrinha residents are doing to educate themselves and fuel their resistance.

The small community of Barrinha in Barra da Tijuca seems to be replicating the Rio das Pedras model with their own Facebook group, #ficabarrinha. The 51 families living there recently received an eviction notice, which they believe is motivated by various private interests supported by Mayor Crivella. Posts in their group have documented the residents learning from other favelas like Vila Autódromo, hosting meetings aimed at supporting women in their struggle, and attending anti-evictions protests (below). These posts provide evidence of the work Barrinha residents are doing to educate themselves and fuel their resistance.

3. Organizing Residents and Communities for Real World Protests

The past several months have seen several coordinated protests put on by multiple communities and their allies. Facebook events, easily shareable and public on the web, were partially responsible for drawing the crowds. The “Unified Act Against Evictions and for the Right to Residence” protest march from City of God to Mayor Crivella’s house on November 13 attracted almost 500 interested people on Facebook (event below), which translated into hundreds of attendees—residents from Rio das Pedras, Horto, Barrinha, Rádio Sonda, Maracajás, Araçatiba, and their supporters.

Unsurprisingly, it was shared on every anti-eviction page mentioned in this reporting. It shows how favela activists are overcoming the potential “fragility” of Facebook-based organizing, or the difficulty of sustaining a movement over time and in changing circumstances. This might be because these activists ground their work in direct action and in-person engagement with each other in a way that complements their online presence. Facebook activity boosts favela movements that grow from an already strong sense of community.

Unsurprisingly, it was shared on every anti-eviction page mentioned in this reporting. It shows how favela activists are overcoming the potential “fragility” of Facebook-based organizing, or the difficulty of sustaining a movement over time and in changing circumstances. This might be because these activists ground their work in direct action and in-person engagement with each other in a way that complements their online presence. Facebook activity boosts favela movements that grow from an already strong sense of community.

Anti-eviction struggles in Rio are often led by a smaller group of resident-activists who organize a broader resident base, although a community’s group of leaders may fluctuate over time. Marina Cunha of Maracajás Road explained: “We decided to create the page [SOS Maracajás] to disseminate all the cruelty that the Aeronáutica is showing us, to cover all our community so that, through Facebook, they would be aware of events related to the evictions.”

Facebook serves the same communication function in Rio das Pedras, a much larger community. Ferreira commented: “We don’t even share this page, we’re normal people, so no one has experience [with] how this world on the Internet works. We just post things and add friends. Rarely do we talk about the medium of the Internet, how this question of adding friends [to the group] works. It promotes itself.” The speed at which the group grew is a testament to the level of online engagement in the favela, as well as the value of Facebook in informing and organizing residents against eviction.

In Rio das Pedras’ case, involving large numbers of “normal people” in the movement to protect the community’s autonomy has been key to its success. Ferreira reflected that she “had to find these people as fast as possible because I understood that only with a large mobilization would we be able to defeat the Mayor’s malicious project.” Zeynep Tufekci, a techno-sociologist at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in the US, writes that “non-activist participation” is one of the hallmarks of “networked movements,” like those growing in Rio’s favelas. Facebook allows activists to recruit residents, spread information, and coordinate struggles across communities—factors that amplify the impact of these movements when they take to the streets.

4. Sending Alerts and Calling for Support

One eviction strategy witnessed in multiple communities is quick lightning eviction demolitions carried out by bulldozers and enforced by shock police, with no to little advance warning to residents. In response, activists use Facebook to alert residents and allies to the presence of the Municipal Guard, demolition equipment, or the surveyors that often precede them.

On October 9, municipal bulldozers entered the West Zone community of Araçatiba in Barra de Guaratiba and arbitrarily demolished three houses while their owners were at work. Araçatiba residents said one of the houses demolished was the wrong one—no eviction notice for it had been served. Since the community is located near beaches and mangrove forests, Araçatiba residents worried real estate speculation would drive more evictions. They quickly created the Araçatiba Resistência Manguetown Facebook page where activists have posted up-to-the-minute updates on any activity in the community that could signal further demolitions, including the presence of police and construction equipment.

This tactic was used by other communities, like Vila Autódromo, to call supporters and media to the community at the first sign a demolition might be imminent. On October 23, 2015, for example, multiple posts on the community page labeled “SOS” and “URGENT” alerted followers to the presence of the Municipal Guard, asking supporters to share their posts and reminding readers that “the last time the Municipal Guard were here in force, many residents were injured in an illegal demolition operation on Mr. Ocimar’s house.”

5. Building Community

Evictions threats cause stress, anxiety, and psychological trauma. Coercion tactics used by public officials and private companies amplify fear of losing a family home, or even an entire community. RioOnWatch has documented the “divide and conquer” strategy, in which individual residents are pushed to abandon their homes with financial incentives or personalized threats in an effort to break down the unity of a community’s resistance. Making matters worse, anti-eviction struggles are often long, drawn out affairs that cycle between flurries of action and long periods of waiting. Take the South Zone community of Horto: the neighboring Botanical Gardens has been trying to expel its residents, many of whom worked in the Gardens their entire lives, since the 1980s, making their struggle over 30 years old.

Favelas rely on characteristically close social ties and community togetherness to weather these demanding fights. As favelas have established an online presence, Facebook has been an additional avenue for building community in trying times.

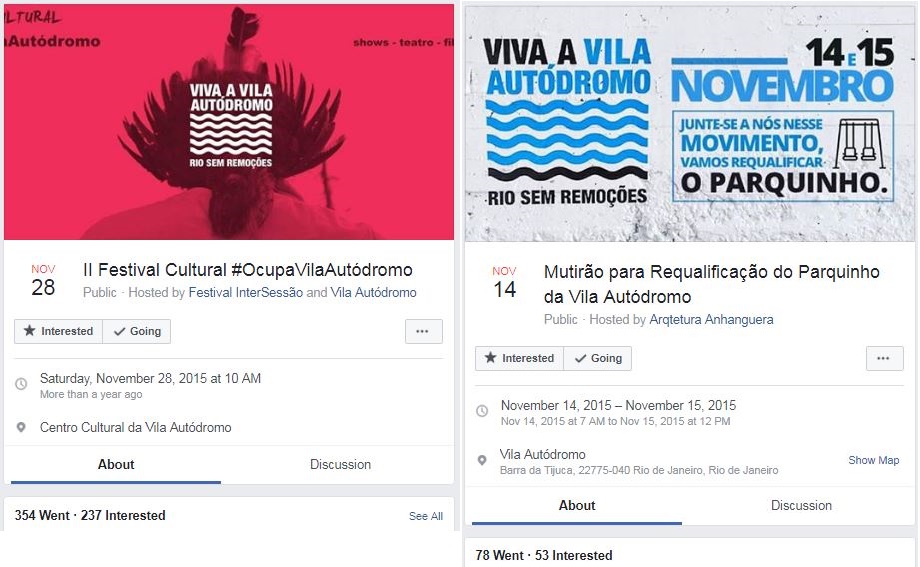

Even as demolitions dismantled their neighborhood and some residents accepted the City’s relocation offers, Vila Autódromo activists continued to host cultural events, workshops, and community gatherings. The Facebook events pictured below are examples of this practice. One is a cultural festival including a workshop on human rights, cinema for kids, live music, a capoeira circle, and a street film festival and discussion. Facebook allowed these events a broad reach and ensured the consistent presence of residents and allies in public spaces. Disseminated through the platform, such social gatherings sustained the struggle as time went on. Local leaders made sure to consistently post photos after each event, documenting the vibrant social spaces that the city government seemed intent on destroying.

Currently, Araçatiba residents are doing the same on their page. Organizers have planned and executed a series of “environmental actions” including the preparation of a community garden and cleanups of the surrounding mangrove habitat. Mutirões, or collective community actions, are a long-standing favela tradition, but organizers have shared them through their anti-eviction Facebook page to strengthen their cause. A photo posted on one event page is captioned “nothing like fighting alongside such a determined and resistant group!”

Looking Towards the Future

Fighting against eviction in Rio de Janeiro often means an all-out effort to save spaces many favela residents have called home their entire lives. Activists use Facebook to share information with each other, garner support, and hold the powerful accountable. To them, there is power in the platform’s potential as a democratic space. Andreia Ferreira from Rio das Pedras told RioOnWatch:

From what I learned related to this, it’s the best mode of communication that exists, principally when you are dealing with the public authority. Because we know that Brazil is a very corrupt country, and they are able to buy even the media. They don’t have a way to corrupt the Internet. In truth, it seems like the best place we have to express ourselves. Even to the point that I think the way for us to start to change our country is through the Internet because it is the only place where we are able to tell the truth, the way it actually is.

Marina Cunha of Maracajás Road agreed:

What I learned is that the Internet used in a wise way is a useful tool to obtain information and also to make new contacts, to help us in this fight.

The continued accessibility of open virtual spaces is currently vital for citizens threatened by forced eviction. Looking forward, we can be certain these activists will continue to be vanguards of creative and impactful social media use in Brazil.