The Botanical Gardens in Rio de Janeiro has threatened to remove the community of Horto, the same community that has been taking care of the “most conserved area” of the Tijuca Forest for two hundred years. In September, Horto residents were warned by a reliable source that Botanical Gardens President Sérgio Besserman Vianna had requested the support of the Military Police to undertake evictions, and the community has mobilized in response once again. The community has survived lightning evictions, shock troops, and real estate speculation. RioOnWatch talked to six Horto residents about their 32-year-long struggle to remain on the land.

Emerson de Souza, current President of the Horto Residents’ and Friends’ Association (AMAHOR), is the grandson of João Batista de Souza Santos, one of the original librarians and gardeners of the Botanical Gardens.

Emerson de Souza: “The reality is that we live in the best preserved part of the Tijuca Forest. And it is not the best preserved part by accident. There is a reason for it. And the reason is the very existence of the community here because our community was created for this.

So, in my grandparents’ time, in my parents’ time, it was the people from the community who went into the forest to put out a fire, to deal with environmental problems. In other words, forest stewardship and all these things have always been done here by the people of this community, Horto Florestal.”

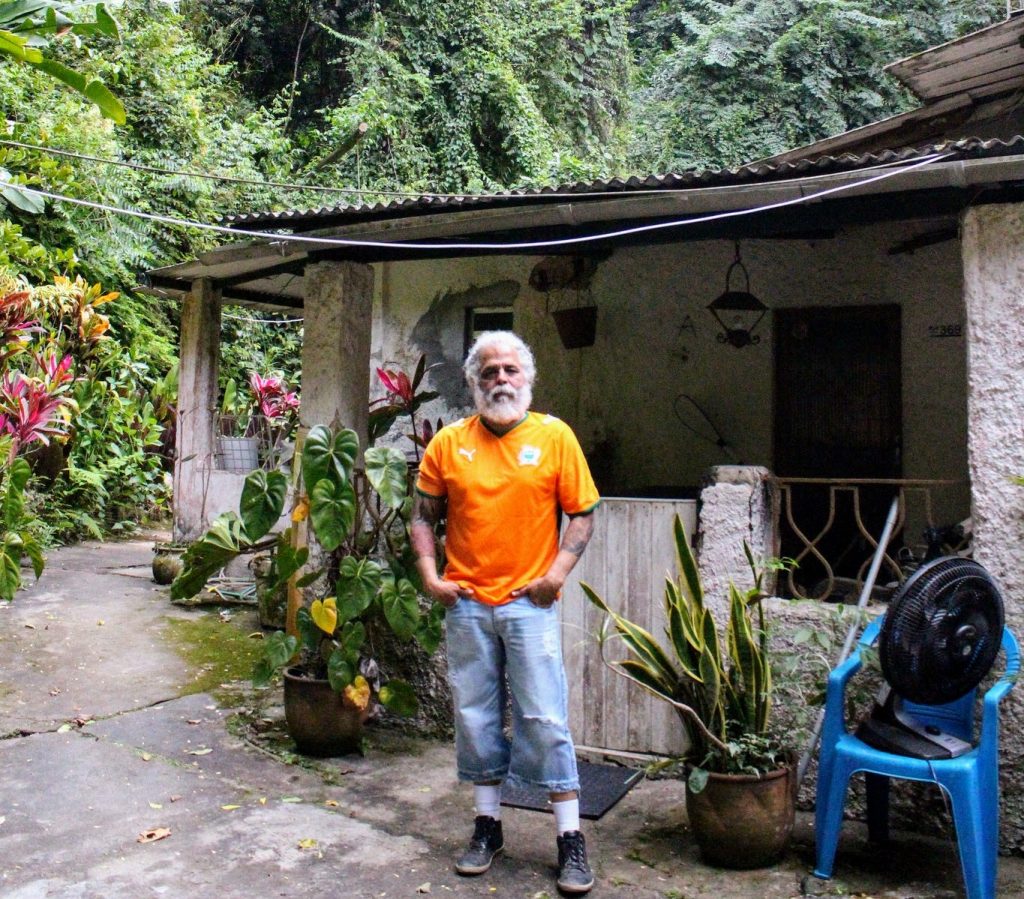

Seu Jorge is a gardener who trained at the Catete Palace, worked in the Botanical Gardens, and gave planting classes in Horto. In his view, the Botanical Gardens has been irresponsible by bringing non-native plant species to the area, such as biribá and jamelão, and throwing away seedlings that could have been donated.

Emerson de Souza: “Seu Jorge is someone who works [taking care of the forest], and everyone knows him. We pass by an area, full of dirt, deforested, and then we pass by again the following month, and it’s there, full of plants, everything is beautiful. But people don’t connect those plants to the activity of someone who went there and planted the area. Who waters the plants every day. We have good projects, we have good professionals here in the neighborhood.”

Jacqueline da Silva is granddaughter of Folha Seca, the first formally hired gardener of Rio de Janeiro’s Botanical Gardens, who passed away this year. Her father died working for the Botanical Gardens, falling from a tree when he was collecting seeds.

Jacqueline da Silva: “Who planted these two palm trees here, that mango tree, that firewood tree, the ironwood? Was it the elite of the Botanical Gardens neighborhood who have been here for 10 years? Was it the new president of the Botanical Gardens? No. It was me, it was my father, it was my mother, it was Emerson’s grandfather. That mango tree there was planted by Aunt Elza. [Those others] weren’t the ones who planted Horto. It was the inhabitants of Horto who planted Horto. So let’s go and fight. We will not allow this injustice against the inhabitants of Horto.”

To reach his century-old house, Pedro Paulo Marins Maciel has to enter through the gates of the Botanical Gardens. Pedro inherited the house from his grandfather, who was a gardener at the Botanical Gardens and built the house with the authorization of the gardens’ director at the time. Back then, the house was in the middle of the forest so the inhabitants could be on watch 24 hours a day to take action if a lantern-balloon fell, or if the forest caught fire during a hot summer. But in 2005, the Botanical Gardens administration erected a wall to expand the park’s boundaries. Pedro’s house ended up within the limits of the Botanical Gardens, isolated from the rest of the community.

Pedro Paulo Marins Maciel: “They put me inside the park. They are the trespassers. Not me. They invaded my territory. Their green is not nature’s green, it’s a sham. It’s the green of the dollar. It is greed. The residents love the [Botanical Gardens] park. What results is a mixture of love and hate. Because you end up hating the park because of the administrators. But the administrators come and go. The park stays. And the park is part of our roots, it’s our history.”

Seu Zeca holds up the whistle of his grandfather, who was one of the former guards of the Botanical Gardens.

Seu Zeca: “They stole so many native trees to make space for the mansions. The bourgeoisie insists on removing the poor community from this area. I believe they shouldn’t even be looking at it like that. What they should do instead is create an organization that focuses on preservation and keeps the community organized and clean.”

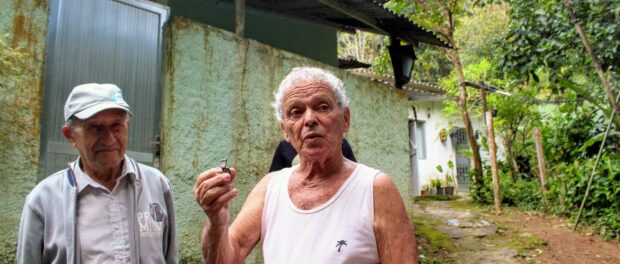

Seu Otacílio came to live in Horto in 1942, when his father began working in the Botanical Gardens and received authorization to build his house on the land. Seu Otacílio considered this place, and the one-room house where he lived with his father, mother and five siblings, a paradise. He said he spent many of his days in the forest from seven in the morning until four in the afternoon, just walking. “You can’t go into the woods anymore,” Seu Otacílio laments. “It’s full of mansions.”

Seu Otacílio: “What head of the family would have peace of mind imagining that when he goes to work, at any moment the phone could ring and he could hear that ‘the police are there in your house and they want to evict everyone’? We are not pests. And we’re not killing trees or anything else here.”

As part of the struggle for housing, AMAHOR has organized free sewing and ceramics courses for the entire community. The course serves to strengthen the community, reuse materials, and generate an alternative future source of income for the students, based on the solidarity economy. As Emília de Souza, former president of AMAHOR, explains:

Emília De Souza: “Society, the press, the formal media, what do they do? They are always trying to criminalize the community, calling us invaders, environmental predators. There was even a journalist who wrote an incredibly derogatory article saying the community only served to reproduce, as if we were animals.

This [solidarity economy] project is also an action to strengthen the community, because with these actions we are showing that the community has the potential to exist in a sustainable way, grounded in solidarity. With it, we are making people increasingly aware that this thing about predatory invaders isn’t real. That we are here to build and contribute to society.”