For the original article in Portuguese by Alejandra S. Inzunza and José Luis Pardo published by investigative news agency Agência Pública click here.

From the grandmother who can’t fetch her grandkids from school to two mothers who lost their sons—one worker and one drug trafficker—Alejandra S. Inzunza and José Luis Pardo report on the assaults on residents’ daily lives in Complexo do Alemão, where a shooting occurs every 30 hours.

During the first three months of 2017 it rained, on average, one of every three days in Rio de Janeiro. In Complexo do Alemão, one of the city’s largest complexes of favelas, a shootout took place every 30 hours, on average. Every morning, instead of looking at the sky to see if she needs to take an umbrella out with her, Marta* checks to see if she can hear the sound of gunshots outside. The door of her house—a modest cement building, home to ten people including her children, nephews, nieces, and grandchildren—is currently secured only by a piece of rope because a bullet destroyed the lock. The gate of the nearby church is covered in bullet holes of different sizes. Marta, a woman with big dark eyes and only a few gray hairs to show for her 81 years of age, developed a new hobby last year, beyond her obsession with soap operas: collecting bullet casings, which she keeps inside a hollowed-out pumpkin, like Halloween pumpkins. The bullet casings are the remnants of clashes between police and drug traffickers.

Alemão residents use similar language to describe their day-to-day reality to that used to describe the wars in Iraq and Syria. But the conflict in the favela complex is more reminiscent of urban guerrilla warfare, with pistols, rifles, and machine guns: it’s either police officers approaching through the sloped streets and alleyways and traffickers responding from behind walls constructed as trenches, or traffickers shooting at police bases and police officers returning fire, sometimes even from inside residents’ houses. This happens almost every day: according to Papo Reto, a collective working to defend Alemão residents’ human rights, there was exchange of fire on 71 of the first 90 days of 2017.

For the uninitiated, it’s difficult to distinguish the sound of gunfire from the sound of fireworks. But Alemão residents have developed the ability to calculate the distance the shots are coming from. This calculation means the difference between taking shelter under the bed or continuing to watch TV; hiding in a room at the back of the house or going out to buy bread; putting life on pause or continuing with daily responsibilities. Their biggest fear is that a stray bullet kills them. Or even a point-blank shot.

Continual gunfire disrupts everyone’s lives. Shootouts begin just after six in the morning, which is when Rosa* heads off to work as a bank cashier, and they start up again when she gets home at four in the afternoon. Sometimes they get going again around lunchtime, which is when Daiene Mendes, a journalism student, goes out to get pizza with a friend; or when Helena* is serving beer at her bar, at which point she and her customers have to hide behind the counter. Shootouts flared up earlier this year when we spoke to Marcos Valério Alves—known as Marquinho do Pepé—the leader of a Residents’ Association. Marquinho described Alemão residents as “hostages of a dirty war that has nothing to do with them,” as a group of four men continued their game of dominoes without any sign of concern.

“In Rio de Janeiro not a single day goes by without shots being fired. We sometimes have a day without victims—rarely, but they do happen,” said Cecília Oliveira, founder of Fogo Cruzado, a digital platform that monitors shooting in the state of Rio de Janeiro. On the fifth of February last year, the Fogo Cruzado app registered a clash in Alemão that lasted for almost a hundred hours.

We were with Marta one afternoon in March when a shootout began. She was walking home hand-in-hand with one of her grandchildren after picking him up from school. She sat down at a plastic table belonging to a little bar situated in between her house and the police base and brought her trembling hands up to her face. “I never know what to do when this happens. If I make a move I get nervous; if I stay still it feels worse,” she says. The gunshots were ringing out somewhere between Marta’s location and that of her other grandchildren, who were waiting for her at their high school. The customers at the bar got up and expressed their indignation. Among them was Raull Santiago, founder of the Papo Reto media collective. “The shooting always starts right when children are leaving school!” he complained.

The customers at the bar agreed: this 4pm shootout is usually the third one of the day. Their theory is that shootouts take place at times when there are more people out on the streets.

Everyone stayed at the bar; no one went running for shelter. A man who came to collect garbage pointed out a huge empty water tank. He couldn’t remember the last time it was full of water. The tank was completely full of bullet holes.

The gunfire lasted around 15 minutes. As soon as the sound of shooting abated, Marta took her grandson by the hand and set off again.

From feudalism to conflict

The houses on September 7 Street in Nova Brasília, one of the 13 favelas that make up Complexo do Alemão, are all different colors but they all have similar bullet holes on the walls. A man can be seen smoking a cigarette at the window of a white building decorated with the three colors of Rio-based soccer team Fluminense. The house next door has a “for sale” sign. A woman appears at the door of her house: its green façade has bullet holes of up to 5 centimeters in diameter. Some children put their hands inside the holes to measure their size. On the other side of the street there’s graffiti on the sidewalk which reads: “The police are going to die.”

This street in Nova Brasília also houses a Pacifying Police Unit (UPP) base and the street next to it is home to a bastion of the Comando Vermelho (Red Command) gang. Complexo do Alemão is considered by the authorities to be the headquarters of the Comando Vermelho, the biggest criminal organization in Rio. The Nova Brasília UPP base is one of eight such bases across Complexo do Alemão, installed in 2010 with help from the armed forces. It’s now more than seven years on and the UPP has not brought peace to the area.

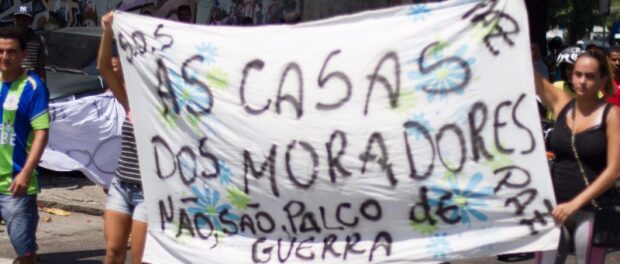

Over the course of last year residents took to the streets many times to protest the fact that they have gone from being victims of a feudal system to victims of what is being referred to as a war. Marquinho do Pepé, from the Palmeiras Residents’ Association, is one of the leaders of these protests. He is 49 years old and has 25 children. He wears thick round glasses and two big necklaces. On his fingers, three rings. On his wrist, a bracelet. All are made of silver. He wears Bermuda shorts and flip flops. He has been living in Alemão “ever since I took my first breath,” which means more than half of the existence of Complexo do Alemão itself, which was founded under a century ago by Leonard Kacsmarkiewcz, a Polish man who bought some farmland in Rio’s North Zone and ended up being confused with a German man, hence the name “Alemão” (“German” in Portuguese).

According to the 2010 census there are now around 70,000 people living in Complexo do Alemão, though some organizations estimate the real number of residents is double that figure.

All around the favela slopes there are streets named in homage to their founders, such as Santa Teresinha, the sister of the Pole who founded Alemão. Other streets have Mexican names, such as Yucatán, because they were built during the 1986 World Cup. The Comando Vermelho’s dominion and violence has also contributed to some names, such as “Green Hell” and “Fear Zone.”

At the end of the 1980s, when Bentto Fabio, a photographer from the Papo Reto media collective, was only 3 months old, his brother was assassinated along with other drug traffickers. Since then, the place of the killing is known as Death Square. “Now my mom has another son who’s in the line of fire, but he’s on a different side,” says Bentto. Death Square became a site for one of the Alemão cable car stations in 2011, which has become a symbolic reflection of the failure of the pacification process. For all its touristic appeal, the cable car station has been out of service for more than a year, since September 2016.

Marquinho do Pepé expressed his anger with the ex-commander of the Nova Brasília UPP, Major Leonardo Gomes Zuma. “I don’t know what’s happened to the police oath to serve and protect, since they do the exact opposite here. People are scared to speak out about it for fear of reprisals. I have got over that fear myself: I’m black, poor, and living in a favela,” he said. The first time we met Marquinho he recalled that in the eight months after the military occupation that implanted the UPPs in Complexo do Alemão back in 2010, there wasn’t a single bullet fired in the community. Until 2013 things were going relatively well.

However, a shootout began right in the middle of our interview with Marquinho. There was a column of smoke visible near the UPP headquarters. We were 500 meters away, far enough in the streets higher up the hill for daily activities to carry on as normal. “The first UPP commanders told us: ‘We are very good at war, but we’re here to bring peace.’ And they did fulfill that mission. But then the command changed and got interested in warfare. We need to ask why. Who wins in this situation? It’s not the residents. We used to have a social project with more than a thousand young people and children taking part. Now there’s nothing left of that project. 99% of the boys who participated are succumbing to drug trafficking,” said Marquinho.

Othello in the favela

One morning Veríssimo Junior, a drama teacher, explained the play Othello to his students in Vila Cruzeiro, a favela located next to Complexo do Alemão, a sort of satellite favela that suffers from the same problems as its neighbor.

To get his students to understand William Shakespeare’s play, Veríssimo tried a soccer reference. He said that Othello was like the coach of a soccer team and that Iago and Cassio were fighting over the captaincy. In the middle of the explanation a student interrupted him: “Teacher, this Shakespeare story is really good, but your example is really bad. Could I give another one?”

In the student’s explanation, Othello was the druglord of the favela and Iago and Cassio were fighting it out to be the second in command. Othello was training a group of fighters for the war in Cyprus against the Turks—in this example the war became a conflict with a rival faction. The Turks were shipwrecked—in the student’s example the enemies in the rival faction died. A party in Cyprus was held in homage to Othello—in the student’s example this became a funk party in a favela.

Veríssimo calls all his students “Hércules” because of what they have to go through to get to school. Often the classroom is half empty because the kids stay at home to avoid the clashes. On other days there will be an armored tank (referred to as a caveirão or “big skull”) parked in front of the school gates. Veríssimo says he’s even seen armed police officers enter the school to pick up a student who, according to them, was involved in drug trafficking. Sometimes shootouts break out in the middle of a class and mothers come running to pick up their children.

In 2016, according to the Rio de Janeiro Secretary of Education, there were only 43 days when no schools were closed due to violence.

“I think what these boys and girls need is not just our charity but rather our solidarity and, above all, our admiration. In the urgent situation in which they’re living, they’ve developed a complex way of processing things, which we should learn too,” says Daniela Azini, a teacher, sitting on a cushion on the floor of her house, surrounded by a dozen orisha statues. “People living on the frontline of a war have to improvise.”

Having never previously set foot in the favela, Daniela started to work in a public school in Vila Cruzeiro five years ago. All she previously knew about the area was what she saw in the press or on TV. Her friends and relatives living in Botafogo, in the South Zone, feared for her safety.

However, during the first two and a half years of the job, Daniela did not hear a single gunshot. Her students warned her that when the World Cup came in 2014 things would change. She didn’t believe it. She used to travel to school every morning with no problems and got used to seeing UPP police officers walking calmly through the streets. Until one day, on the eve of the World Cup, one of her students brought her a bullet casing. There had been a shootout the night before. It was then that all the horror started. “Now, when I speak about pacification, I put the word ‘pacification’ in quotation marks, because my opinion has changed a lot,” she says.

Soon after the World Cup, Elias Maluco, the druglord of the favela, closed the school for a day as a show of mourning for a drug trafficker who had died. That same year, Daniela joined the Facebook page a Vila Cruzeiro resident had set up to warn people when and where shootouts were taking place. She also joined WhatsApp groups in which residents share information and organize themselves in order to stay safe. In 2015 she was on her way back from a school trip to a museum when an intense shootout started. Once in 2016 she went home crying, having a panic attack, because the gunfire came really close to her. “I feel a big connection to this community. The only time I’m scared to teach in the favela is when the gunfire starts,” she says. When the shootouts start Daniela leaves her classroom on the third floor and goes down to a room on the ground floor. It’s the best place to stay safe from the gunfire because the walls are thick. She tries to calm her students down. But when the gunfire comes close, the students end up trying to calm their teacher.

Ever since they were young children, the students have had to deal with bullets, armed men on the streets, police operations, and people being injured by gunshots. There are few places to go to escape this tension. Since the beginning of 2017, journalism student Daiene Mendes has been using her blog to complain that the cultural, social and sport center in the Favela da Grota, which was built before the Olympic Games, has been closed due to lack of money for maintenance; that the local state-funded ‘Biblioteca-Parque’ library, which used to function in one of the cable car stations, is also closed and occupied by the police; that a Family Clinic that used to operate in one of the highest parts of Complexo do Alemão was closed for safety reasons. “This is the legacy of abandonment,” she wrote.

The therapist of the favela

In the whole of Complexo do Alemão there is not one mental health center for residents. Mônica Cirne offers the nearest thing, even though as a physiotherapist she only treats residents’ physical ailments.

In the rooms of the Instituto Movimento e Vida, a physiotherapy clinic set up to treat Alemão residents, there are toys all over the floor. “I see the consequences of the current situation,” Mônica says. By this she means the victims of violence: children with facial paralysis, 14-year-olds with signs of strokes, people with hypertension, diabetes, heart attacks, among other things… “I have a pyramid of the cases I treat and the largest part of that pyramid are people with neurological conditions brought on by stress,” says the therapist, wearing glasses that make her eyes seem bigger. She also helps residents with broken bones or gunshot wounds.

Mônica is the only person who has been treating Complexo do Alemão residents, for free, over the last ten years or so. She has a waiting list and attends to 18 people a day, twice a week. “Anyone who has any problem and needs physical rehabilitation comes looking for me, whether it’s because they were shot or because they fell off a roof. They all come to see Mônica, but Mônica is old and tired,” she says. If anyone has an illness she looks after the consequences of that illness. Among her patients there are people with cancer, children with hydrocephalus, and the children of crack addicts. When she’s at home and hears a shootout, she knows that the next day she will have a lot more work.

At the beginning of the year the police took over people’s houses

On one morning in March, Rosa couldn’t get into her house. Broad-shouldered with a long nose and big, sunken eyes, she lived in an area occupied by the police. Her house on Praça do Samba in the Nova Brasília favela was right in the middle of crossfire. UPP officers occupied the rooftops of some houses, including hers, and fought the drug traffickers from there. “It’s been two or three months that we haven’t been living there. There could be a shootout at any moment and someone could get shot,” she said.

At the beginning of 2017 the UPP forces started to build a base just meters from Rosa’s house. It’s common for them to go up to the top of her neighbors’ houses where they take up position as snipers. “One day my mother called me saying that the police were on my rooftop and didn’t want to leave. They were saying that they were going to stay up there because it was very dangerous for them to be on the streets.” This invasion of Rosa’s rooftop lasted for two months.

The creator of Defezap—an app that helps citizens denounce State violence—Guilherme Pimentel, helped Rosa make a complaint to the State Prosecutor’s Office based on video footage of the occupation. As a result the police left Rosa’s house… only to occupy other people’s houses instead. “Complexo do Alemão residents use the app to denounce repression during protests, police aggression towards residents, and executions. They have reported seeing police carrying bodies,” says Guilherme. According to residents, house occupations are still ongoing, despite the notoriety the case gained.

On April 23 there was a public hearing at the Legislative Assembly to discuss the house invasions. During the hearing the ex-commander of the Nova Brasília UPP, Leonardo Gomes Zuma, said that only one house had been occupied and defended the policy, stating that the invasions were part of a “strategy to occupy the territory” and protect police officers, who were the victims of gunfire and grenades. We asked the ex-commander for an interview but he refused our request. “He’s not much of a talker,” was the reply we received from his spokesperson Ivan Blaz.

Raull Santiago from the Papo Reto media collective stated last year that “the scale of the absurdity was getting bigger and bigger. It all started with the permanent police presence in 2010 and now, in 2017. We’re seeing the same police force invading houses and kicking out the residents.”

Rio de Janeiro’s Public Ministry denounced ex-commander Zuma as well as the commander of the Pacifying Police Coordination (CPP), Colonel André Luiz Belloni Gomes, for the house invasions. The Military Police officers involved claimed that the houses in question were abandoned, but investigations revealed that at least five houses were occupied against the will of residents. The officers are accused of holding residents under duress and for house invasion. Zuma is no longer the commander of the Nova Brasília UPP.

Rosa is terrified of stray bullets. Many years ago her brother was shot when caught in crossfire at a funk party. He was paralyzed for ten years and passed away recently. Rosa’s fear is that the story will be repeated with another member of her family. All the buildings on her street bear some sign of the conflict. Rosa used to play on the street when she was a child. Her daughter, now 15, used to play outside too. But her nephews, who come over to her house after school, are forbidden from doing so. There are days when Rosa buys extra food so that she doesn’t have to leave the house during a shootout. She watches the soap opera on TV and tries to keep her routine going because the bullets she hears don’t actually reach her house. However, that fact doesn’t stop her daughter and her mother from hiding in the back room.

One night she came home late and it was dark. A police officer opened fire and her only thought was to shout desperately that she was a resident, so that they didn’t confuse her with a criminal. During the first half of 2017, following a police invasion by the Special Operations Police Battalion (BOPE), she decided to leave the house where she’d lived for 40 of her 44 years. “We’re leaving. This is not our war,” she explained via WhatsApp.

Peace: 500 meters away

In a small cheap loans shop that seems more like a beauty salon because there are always women doing their make-up there, there are two women. The first is well known in Complexo do Alemão because her son was a popular moto-taxi driver who was killed by a police officer. The other woman is the mother of a drug trafficker, and because of his job she rarely mentions his assassination.

On Guadalajara Street, in the Nova Brasília favela, one of the lower areas of Complexo do Alemão, silence is an anomaly. Denize Moraes, 51 years old and proudly “born and raised” in Complexo do Alemão, breaks the silence with a laugh. “It’s strange, I haven’t heard gunfire today.”

Denize does her nails while she serves a few customers. Her shop is decorated with 33 photos of her son Caio. He has a different style in all of them. She talks of gunfire as if she were talking about the rain. “I still remember my first experience of a shootout. I think it was in the 1990s, I hadn’t had my son yet. It was a dark day. It seemed like being in Iraq. The next day, when I went to the bakery it was full of bullet casings and by the time I got home the shooting had started again,” she recalls. Since that day gunfire has become part of her daily life, right up until it took the life of her son Caio, who was 20 years old.

It was May 27, 2014. Caio called Denize at 6:52pm. He said that he’d stopped working that day because the neighbors were protesting the arrest of a resident who had been accused of drug trafficking. “For a moment I had a pain in my back. But I never thought it would be because my son had just been shot in the back,” Denize said. The police had sprayed the protesters with pepper spray and everyone ran to avoid it. A police officer shot her son from a bakery. Denize was at home when a few boys came over to tell her the news. In her hurry to find her son she couldn’t manage to find her shoes, bag, or ID. When she arrived on the scene Caio was already dead. The police officer’s justification was that he misfired and that he was aiming at a criminal. “That’s a lie. He was very close. The bullet entered through [Caio’s] back and remained in his collarbone. So we knew who fired the shot,” she says.

The community united behind the case because Caio had worked ever since he was a child. He had two sons and he had built his own house. Denize says that when Caio was killed 70% of her happiness disappeared. “He always said that he’d never work in anything bad because he wouldn’t be able to cope with a bullet. And it was true: he couldn’t,” Denize reflects.

In Complexo do Alemão there are dozens of mothers of drug traffickers who are killed who do not tell their stories. No one unites behind those mothers: they are marginalized. “I think the way they’re treated is really ugly,” Denize says. “A mother is a mother, after all.”

Paula*, a woman with curly hair tied in a ponytail, comes into the shop. Paula isn’t wearing make-up and her voice is muted, broken. She is scared and distrustful. It doesn’t take long for her to start to cry as she recalls that day. “My son out there, all alone…” she begins to say before she breaks down. Denize offers Paula a glass of water. It’s hard for Paula to say what happened.

Her son was killed six months ago, at the age of 24. He had only been involved in the drug trade for a little over a year when he was killed. She had never seen her son with a gun. He had left home. Paula didn’t know where he was living at the time. She found out through other people that he was involved in crime. “I don’t know what went through his mind,” she despairs. He was shot in the head in a shootout with police. “They didn’t let me get close to him. The police officer shot me with a rubber bullet and told me to go away. I said no, that he’d just killed my son. If he wanted to he could shoot me too.” She cried and the police officers insulted her. Her daughter-in-law was one month pregnant when her husband was killed. “When the baby was born I was happy because he looks just like my son,” she says, showing a photo on her phone.

That afternoon, Denize took us to a wall behind a barbeque bar where someone had written: “Eternal Caio.”

The walls of Complexo do Alemão remember the dead, the police threats, and the feats of the traffickers. They tell a story of violence and of a promised peace that turned into a daily conflict. On one of the walls close to the edge of the community there is a piece of graffiti with an arrow that shows the way to the exit of Complexo do Alemão. It says “Peace: 500 meters away.”

*These names were changed for the safety of the people interviewed.

This report is part of the En Malos Pasos project, special coverage of violence in Latin America.