In its sixth annual edition, this year’s Urban Peripheries Literary Festival (FLUP) took place in Vidigal in the South Zone of Rio de Janeiro with the theme “Revolution, Choose Yours,” which sought to engage with the 100 years since the Russian Revolution and 50 years since May 1968. The honoree of this year’s event was the playwright and actor Oduvaldo Vianna Filho, otherwise known as Vianinha, an activist-artist concerned about social issues who had some of his work censored during Brazil’s military dictatorship.

The event, which took place from November 10 to 15, was attended by numerous important national and international figures from the artistic, academic, and media fields, including the political philosopher, activist, and feminist Djamila Ribeiro; writer and author of City of God, Paulo Lins; journalist and political scientist Leonardo Sakamoto; French anthropologist Françoise Vergés; French queer activist Sam Bourcier; world-renowned spoken word poet Saul Williams; and French filmmaker Laurent Cantet.

FLUP’s range of activities included the Rio Poetry Slam, a spoken word poetry competition; the Think FLUP (FLUP Pensa) project, which sought to train authors, promote new talent, and publish a book with the best submissions; and the FLUP Park (FLUP Parque) program—artistic and literary gymkhana contests for children.

This year, the FLUP Park program expanded and, through the ‘Vidigal History Gymkhana’ coordinated by Bárbara Nascimento, ran several activities to revive Vidigal’s history, situating the community’s residents as protagonists. Nascimento, a teacher and researcher, was invited by Júlio Ludemir, the creator of FLUP, to participate in the event and curate FLUP Park. As a result, she decided to link her academic and personal research on memory with the FLUP Park activities in Vidigal.

“The first challenge we had was that FLUP Park, which is this specific part of FLUP aimed at children, usually operates in schools. It’s an inter-school competition. In the case of Vidigal this was difficult because there are not many schools… Then I thought to myself, well, if I can’t do an inter-school competition, let’s do a contest across Vidigal,” Nascimento explains.

As such, Nascimento decided to create the gymkhana teams according to different areas of the favela. Vidigal was divided into 5 different areas, each with a leader and a team of children and young people to fulfill the task of reviving the memories of each area. The five established regions were the area known as 314, Pedrinha, Principal (a stretch of Avenida Presidente João Goulart, the main road), Rua Nova and Rua Três (area located in the lower part of the favela), and Área do Alto (the top of the favela encompassing Arvrão, Jocabal, Alto, and 25).

“And the coolest thing is that besides dividing our teams by areas, we also involved the institutions. The boxing non-profit Instituto Todos na Luta, local schools, day care centers, the theater group Nós do Morro, capoeira, soccer,” Nascimento says, adding that “The result was incredible.”

The leaders chosen for each team were Vidigal residents and therefore they already brought their own local narratives, reinforcing the gymkhana’s objective. The idea was for each team to conduct research before the event on the accounts of local history as told by the residents of their areas. This endeavor emphasized the residents’ narratives about urban transformations as well as the history of evictions and residents’ resistance, also drawing on representative musical and artistic features of the areas. The three-day gymkhana had several activities: each team had to present a musical genre from its area, create a rug and kites that told the local story, and engage with cartoonists, among other artistic and literary activities.

Cida Costa, a poet and member of the theater group Nós do Morro, shares a little about her experience in the gymkhana: “I was representing Pedrinha. And I made this partnership with these groups, with these schools, to tell the history of that specific area, which I took from the Favela-Bairro [upgrading program] in 1998, 1999, up until more or less this decade.”

A Pedrinha resident and team leader, she shares how much the historical revival of the area has meant to her: “Pedrinha’s history moved me deeply, and I think not only for me, I think for my friends and companions and for Vidigal, because it is an area that has always been compared to the Gaza Strip. And all of a sudden, we really pause to dive into our history and tell the story of the neighborhood.”

During the research period, her team went looking for photos from local residents that depicted what Pedrinha once looked like. In addition, they sought to portray historical figures of the area and the musical genre that marked the local history: funk.

“Especially in Pedrinha, because at the time baile funk parties were held in Largo do Santinho, that’s why the area became attached to funk,” says Nascimento. Costa adds that “Largo do Santinho is at the mouth of the entrance to Pedrinha. And this baile funk party was very, very famous… People from outside the area came up to enjoy the Largo do Santinho party. And the people in Pedrinha would spend the entire week preparing for the event.”

Sérgio Henrique, a member of the Nós do Morro theater group and a coordinator of social projects related to culture, and Robert Pacheco, a teacher at the Vidigal women’s soccer school, were the team leaders who represented the Alto do Vidigal area (at the peak of the community). For them, the activity was important for reviving and discovering stories from the area, for integrating residents, and for serving as a basis for future struggles and activities.

“And then in this research when we were running around the community, going from door to door, even those of us who were raised here in Vidigal, we discovered several things: that there used to be a spring by the side of our house, that the people had no plumbing and went to a spring up there, carrying buckets on a broom handle and passing them, taking turns, you know, making a line to pass buckets of water,” says Henrique.

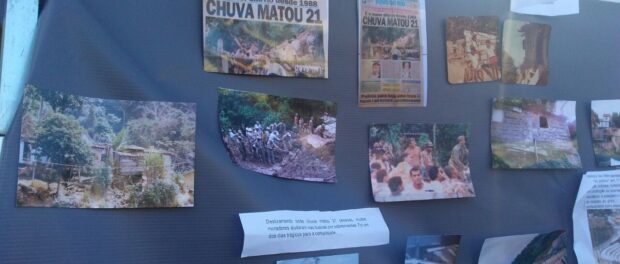

In addition, the research brought up two landmark events for the area’s residents: a landslide in 1996 that killed 21 people and a rockfall that killed around 25 residents. The affected families were never compensated and did not receive any government help to rebuild their lives. The construction of the Vila Olímpica, one of Vidigal’s main venues for sports and community activities, and the creation of Sitiê, an old garbage dump that was transformed into a local ecological park by residents, also emerged from the research conducted by the team. In relation to more recent events, the group also focused on Vidigal’s gentrification process, with the rising cost of living, rising real estate prices, new residents arriving, and old residents leaving—issues that have hit this area in particular.

Ninho de Paula, a capoeira instructor, was in charge of leading the team reviving the history of the 314 area. “I talked about 314, a symbolic area in this 40-years process of resistance against evictions,” says de Paula.

This neighborhood is particularly important because it was where the first occupations of Vidigal began. In addition, it was the area visited by the Pope in the 1980s and where important historical local leaders in the struggle against evictions can be found. To represent the Pope’s visit, an important moment for Vidigal and for the 314 area, a reenactment of the visit was staged by a child together with Armando, a leader of the Residents’ Association in the fight against evictions in the late 1970s, who sang a song.

Meanwhile, the Principal area was represented by team leader Júlia Giglio, a lawyer and trainer at the boxing NGO Todos na Luta, who focused on portraying the 1980s.

Meanwhile, the Principal area was represented by team leader Júlia Giglio, a lawyer and trainer at the boxing NGO Todos na Luta, who focused on portraying the 1980s.

“It was the time when there were many [local collective action] mutirões, when we got water, infrastructure projects. And since those of us in the [Todos na Luta] project have also held a number of mutirões in recent years, we made an association between one thing and the other… We wanted to show that unity was important in the 1980s, solidarity was important, and it continues to be important… I think it’s time to revive unity, right?” says Giglio.

The area’s historical research also tied the NGO’s work to the area’s history. Created by her father, Raff Giglio, the Instituto Todos na Luta seeks to promote education through sport for the favela’s children, and has discovered much promising local talents. In addition, Giglio’s team chose Black Music as their musical genre, represented through a choreographed dance presented by the children on the team.

“It’s the first time, in 39 years of working with art, that I’ve seen Vidigal being brought together in this way with all the different areas… These divisions by area for what we call a literary gymkhana mobilized the entire community because we created a cross-cutting event, which involved not only the schools but all the institutions,” sums up de Paula.

For the entire team, the event was important for reviving history and community bonds, and for inspiring future educational and cultural projects in Vidigal.

“We all won in this gymkhana, in this partnership with FLUP, in this project around memory, in this research initiative. From this event we have come up with several ideas—in our minds which are bubbling with inspiration—on the impact we can have through this work,” comments Cida Costa.

Robert Pacheco hopes “that children, nowadays, are able to have a better understanding of Vidigal. Learning for their future.” He adds: “I hope this experience will inspire great writers and poets.”