Community activists and family members packed Rio de Janeiro’s Theater of the Oppressed on the evening of Friday, December 8 as part of a community campaign against police operations in the city’s favelas.

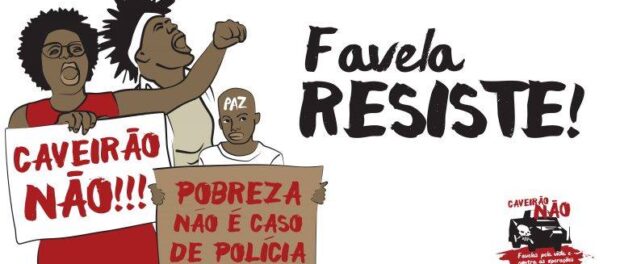

The campaign, “Caveirão Não: Favelas Pela Vida e Contra as Operações!” (No Tanks: Favelas for Life and Against Police Operations!) launched with three days of events last week, led and organized by the Network of Communities and Movements Against Violence. Marches, press meetings, and film screenings called attention to police violence, highlighting its disproportionate impact on Rio’s young black men.

According to the Brazilian Forum on Public Safety, nearly 22,000 Brazilians lost their lives in police operations between 2009 and 2016. Of those killed, 99.3% were men, 81.8% were between the ages of 12 and 29, and 76.2% were black. 2016 alone saw 4,224 deaths attributed to conflict with civil and military police—up 25.8% from 2015. At Friday’s event, Complexo da Maré community journalist and Network Against Violence representative Gizele Martins reminded the audience that “the fight for black lives cannot be a secondary fight… It must be central to any political agenda.”

Community-level data on police operations are harder to come by, but the Caveirão Não! campaign hopes to change that. Campaign organizers are currently assembling a dossier documenting the number of police operations in favelas, their local impacts, and public funds spent on such operations. Martins reported that the campaign has begun meeting monthly with community members and international partners alike. “We want this campaign to reach the whole world,” she said.

Mothers of the victims of police violence also spoke that evening, demanding justice for their sons’ killers and support for favela residents. Network Against Violence representatives Ana Lucia de Oliveira and Maria Dalva Correa, both mothers to sons killed by police, led the evening’s opening discussion. Oliveira’s son Michel Antonio de Oliveira da Silva was tortured and killed by militia—groups comprised of armed off-duty cops that assert control over certain territories—in the North Zone neighborhood of Ramos in 2008. Correa lost her son in the 2003 Borel Massacre when four young men were killed in a police operation in Rio’s Tijuca neighborhood. Though neither killer has faced charges, both women remain hopeful. “The community is making progress,” said Oliveira, “and will progress much further.”

Later, organizers showed the documentary “Luto Como Mãe” (I Fight/Mourn Like a Mother) and a preview for the upcoming film “Nossos Mortos Têm Voz” (Our Dead Have a Voice). Seven years ago, “Luto Como Mãe” showcased the courageous protests of mothers of the victims of the Acari, Via Show, and Baixada Fluminense massacres of 1990, 2003, and 2005, respectively. Now, “Nossos Mortos Têm Voz” directors Fernando Sousa and Gabriel Barbosa hope to contribute to the continuing struggle against police impunity. Produced by Quiprocó Films in partnership with the Grita Baixada Forum, the Center for Human Rights at the Diocese of Nova Iguaçu, and Misereor, their documentary returns to Greater Rio’s Baixada Fluminense region to follow the struggle of six women as they seek justice for their sons and brothers.

One of the film’s protagonists, Joanna D’Arc Mendes, was present Friday evening. D’Arc Mendes lost her youngest son, Flávio Mendes Pontes, in March 2004. Thirteen years later, she recounts the story like it was yesterday: “Three police invaded my house saying they had received an anonymous report that we were hiding drugs. They searched everywhere and found nothing… They ripped my son from my arms and shot him out in the street.” Of the three police involved, one had his charges thrown out, while the other two would go on to participate in 2005’s Baixada massacre—the bloodiest in the history of Rio de Janeiro.

Mendes, Oliveira, Correa, and all the other women who continue to march for their fallen loved ones are fearless. All of them—despite psychological trauma, declining health, even death threats—continue to pursue justice in the face of rampant impunity. With the support of filmmakers, community organizations, and international partners, they may yet find solace. One thing is clear, though. They will not be stopped. “We must fight,” said Oliveira. “We can not give up. May we never retreat.”