For the original article in Portuguese by Lígia Mesquita published by BBC Brasil click here.

In 20 years, do you see yourself being mayor of Rio de Janeiro?

High school senior Larissa Vieira had never thought about that possibility when she heard the question. The dream of the 17-year-old—resident of the Vila Kennedy favela in Rio de Janeiro’s West Zone region of Bangu—is to be an actress. And she strives to achieve her dreams by taking free classes in a community space sustained by the sheer determination of her teacher and those that attend to it.

Vieira had never talked about politics. She didn’t even really understand what it meant in practice.

She didn’t know that “a person from the community could be there [in city government].” And her perception of politicians was that “they only know how to steal.”

Now, her view is that reality could be something different.

“I didn’t even know what I could do to change things. Now I’m beginning to learn. I hope this goes back to being a better place,” she says, referring to the community where she lives.

The teenager describes having learned a lot about politics—including that it’s something “that you do on a daily basis, with little actions or even engaging deeper”—from one night of conversation at Carol’s home, a resident of the same community who Vieira didn’t previously know.

She learned from her theater group that there would be a chat there about the community’s issues and other topics and decided to go see what it was about.

Now, the daughter of a mechanic and a radiology technician at a public hospital imagines herself being a politician one day and, who knows, maybe even running the city where she lives.

Politics on the agenda

The informal meeting was part of the TodoJovemÉRio (EveryYouthIsRio) festival, an event that took debates on political and social issues to 40 homes of youth from Rio’s peripheral areas, favelas, and suburbs, with one of its goals being to train new leaders.

The festival, which wrapped up on January 27, was organized by the Youth Networks Agency, which created a methodology to help youth develop their own solutions for the favelas where they live. The Networks’ methodology has already been exported to the United Kingdom where it is used in projects in London and Manchester.

For the first time since it was created in 2011, the Agency decided to change the focus of its work and talk about politics, at a moment in which Brazil is experiencing huge polarization and does not see new leaders emerging.

Polarization that Vieira, for example, sees and disapproves of. She had already heard about the political right and left and had no idea how to “define this” in terms of ideologies but thinks there are “too many labels.” “People like to say this to divide people. And it’s useless. You have to think about what the people need, not continue to separate them,” she says.

Engagement

The project coordinators, mostly youth who came from other jobs at the Agency, demonstrated how people can take part politically in life in society. They taught, for example, how to contact the city government to request effective improvements for communities (lighting, equipment repair) and also advised how to occupy public space to reach more people, be it through art or some other activity.

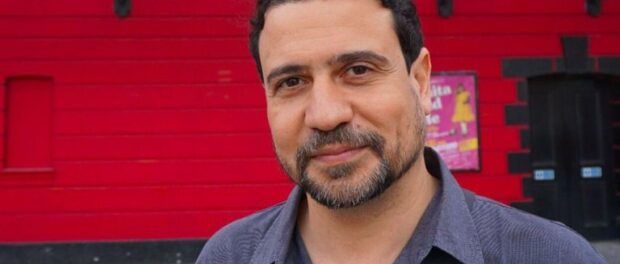

For cultural producer, writer, and director Marcus Faustini, founder of the Youth Networks Agency, before trying to strengthen one single political movement, it is essential to help politics itself gain space in society, allowing multiple movements to emerge at the same time. And with them, diversity grows. “We are preparing these youth so they are respected and heard in the next election cycle,” he tells BBC Brasil, as someone who also grew up in a peripheral neighborhood.

He hopes that by the end of the year 200 houses in peripheral regions will be engaged with this proposal for debating and doing local politics.

“We wanted residents to open up their houses because homes are also political spaces. It’s a place of subjectivity. Last year the most important house in Rio was [musician] Caetano Veloso’s in front of the beach [where a lot of politicians like former presidential candidates Marina Silva and Ciro Gomes, among others, gathered to talk with artists and intellectuals]. If his house is important, why isn’t a house in the periphery important? If politicians go to people’s houses in Rio’s South Zone [the richest region in the city], why not go to houses in peripheral areas?” Faustini asks.

Two decades until the election

Some movements that arose in recent years try to put politics on the agenda and from there seek to launch a possible new name to dispute elections. That’s the case of Agora! (Now!), for example, which considered launching TV presenter Luciano Huck as a presidential candidate for 2018. But most of these movements are made up of people with more purchasing power, like business owners or lawyers.

“The discussion about Brazil’s future political leaders can’t be restricted to the middle class. If we want a renewal, we also need to look to peripheral areas,” Faustini says.

For Faustini, thinking about beginning to train leaders now so that they are feasible candidates in 20 years is not too long a timeframe.

“What we’re proposing is very serious. We are stimulating a desire so that marginalized communities want to have someone becoming mayor of Rio in 20 years. This requires a process of construction—it’s not just saying “I’ll go” now, because they’ll say you’re coffee and milk,” he reflects [using a colloquial expression for someone who is too young or inexperienced to participate effectively].

Until then, he says, these young people could also create new parties, because participants in the TodoJovemÉRio meetings did not fully identify with the existing parties.

How it works

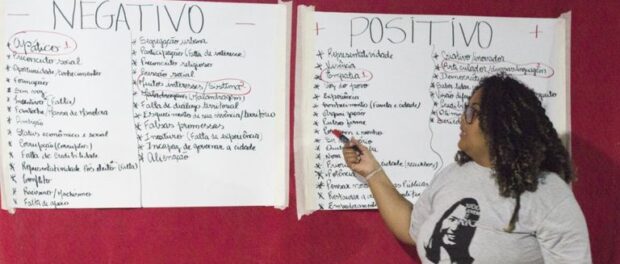

Holding a poster that says “Trustworthy Leaders, Representative of the Favela,” Rebecca Vieira, 26, spoke to a group of young people, all standing up in a house in the favela of Batan, in West Zone’s Realengo region.

“I sent messages through WhatsApp, through Facebook Messenger, I called, I bothered people. And this theme [written on the poster] was the one that came up the most,” the publicity student explained. “What does it mean? Often we don’t know how to have a conversation with those people who are leaders of the favela, who are part of the Residents’ Association.” Afterwards, she asked the group to identify the advantages and disadvantages of a mayoral candidate from a peripheral community, like them.

Among the positive points, the youths said that a candidate from the community would actually understand what the problems for peripheral areas are and would be able to help solve them. It would also be someone who would speak the same language as them, who would look at those areas more carefully. Curiously, they also said one’s roots in a poorer region could be a negative point because, some of them suggested, the candidate would suffer prejudice and could become fascinated by power—and corruption.

Rebecca Vieira had already taken part in a Youth Networks entrepreneurship project and thus was helping at the TodoJovemÉRio festival as a type of leader. Besides leading that whole session, she helped to select the houses that hosted the debates and called up people in the community.

The creation of the festival was “daring,” the student says, “because we live in a political moment in which people ‘meet’ on social media, writing long posts, complaining, but no one effectively does anything to change anything.”

From her discussion group, some people have already come away with plans to dialogue with the Residents’ Association to see what needs to be done in the community. Others have ideas to occupy the streets of Batan with festivities carried out however possible.

According to founder Faustini, the idea of the festival is to plant a seed so that young people become active in any way they can and want in their communities, and don’t look with contempt at something important like politics.

Change

Street vendor and rapper Bruno Souza, 17, lives in the Costa Barros favela, close to Pavuna in Rio’s North Zone, and has always despised the idea of “politics,” believing that it only involves “thieves” and that nothing will change.

He heard about one of the festival’s debates through a friend and decided to go “see what it was” and learn if, indeed, he could do something to improve life in his community.

“I know it’s hard to change things here—an area of risk, the drug trafficking prevents a lot. There are no skate lanes for us to hang out in, we need to go to Madureira. There are no pools for bathing. The only thing we have here is the shootings,” he says.

He doesn’t risk imagining that one day he could work in something related to politics, but he thinks it’s important that people from peripheral communities “enter the system.”

“It has to be someone who came from the periphery, it’s useless to elect another person up there [in city government] to change something they don’t know. It has to be someone who’s here, who knows what happens in our daily lives.”