This is the third article in a four-part series on Internet access in favelas and urban peripheries in Brazil. Don’t miss parts one and two. For the entire original article in Portuguese by Escola de Jornalismo Énois and data_labe published by Nexo Jornal click here.

The Marco Civil da Internet (Brazilian Civil Rights Framework for the Internet) passed in 2014, is the law that works as a kind of constitution of Brazi’s Internet. It defines user rights and operating guidelines for the government and businesses. The fact that part of the Brazilian population remains disconnected from the Internet—whether due to lack of supply or high prices—contradicts at least two of its premises. The first is that the network “must remain public and unrestricted to the population.” The second is that the Internet is “essential for the exercise of citizenship in Brazil.”

“The Internet has become a basic necessity,” says Rafael Zanatta, lawyer and researcher at Idec (Brazilian Institute for Consumer Protection). “In Brazil, with the Marco Civil, you start to perceive or analyze the Internet through this political prism. Having Internet access allows you to be a citizen, to engage politically, and to have meaningful social relationships,” he says.

Today many public services can only be accessed online. The issuing of invoices, income taxes, and enrollment in Bolsa Família (welfare) or the Enem college entrance exam, for example, are basic services that depend on the Web. “The digitization of these services will create a type of elite citizenship. It doesn’t make sense for the government to worry about digital citizenship if at its base there aren’t public policies that guarantee connectivity, access, and the digital culture essential to good citizenship,” says Zanatta.

“The Internet is a tool of political strategy that enables us to broaden rights,” says Sil Bahia, creator of Pretalab, an initiative that works for the inclusion of black and indigenous women in the field of innovation and technology. For her, the Internet is a space to claim rights.

“I think we need to learn to inform our [communities] that the Internet is more than what we think and that it could even be a place for education.” – Sil Bahia, Pretalab Coordinator

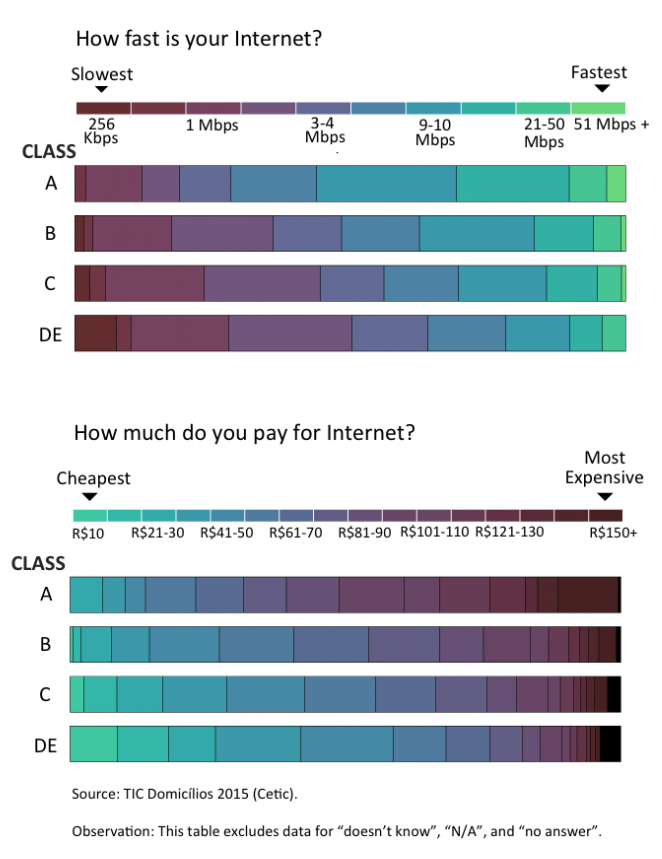

The percentage of those who rely on cell phones to access the Internet is highest among lower-income populations. In classes D and E, 28% of people are connected and, of these, the majority (65%) access the Internet only through cell phones. Mobile networks offer cheaper plans and prepaid options that cost less. The problem is that they do not offer all the possibilities of a fixed connection. It is very difficult to watch a video on a 3G connection or learn to program on your phone only, for example.

In addition, mobile networks offer limited data packages. In other words, you can only consume a certain amount of Internet data. Once the limit is reached, the consumer gets disconnected or relies on so-called “zero-rating” plans, where access to a particular application, such as Facebook and WhatsApp, does not consume data. These deals, signed between phone providers and Internet companies, are sold as promotional offers, but many consumer protection advocates say they are not always beneficial. In addition, they infringe the principle of net neutrality contained in the Marco Civil, according to consumer protection organizations.

In addition, mobile networks offer limited data packages. In other words, you can only consume a certain amount of Internet data. Once the limit is reached, the consumer gets disconnected or relies on so-called “zero-rating” plans, where access to a particular application, such as Facebook and WhatsApp, does not consume data. These deals, signed between phone providers and Internet companies, are sold as promotional offers, but many consumer protection advocates say they are not always beneficial. In addition, they infringe the principle of net neutrality contained in the Marco Civil, according to consumer protection organizations.

Net neutrality dictates that all online services (websites and applications alike) are to be available in the same way, without speed or access barriers. This guarantees access to different online content regardless of the user’s contract plan. “Zero-rating” plans for cell phones may end up limiting the experience of those who cannot afford more data and remain restricted to apps that do not consume the data plan.

According to Facebook itself, 102 million people access the social network every month in Brazil. Out of these, 93 million people access the platform only via mobile devices. And a lot of people end up using only Facebook: a Mozilla Foundation survey showed that 55% of Brazilians think that Facebook is the Internet. The figures are similar for other developing countries. WhatsApp—also owned by Facebook—is used by almost 100% of connected Brazilians.

“People’s right to information ends up restricted as a result of an undemocratic distribution of infrastructure and an undemocratic distribution of Internet access.” – Flávia Lefévre, lawyer and council member of the Internet Management Committee

Around the world today, some mobile network carriers provide Internet services under the same logic as cable TV. Cheaper packages only give you access to basic services like WhatsApp, email and Facebook. The more expensive ones offer Netflix, YouTube and other Web content. The idea of net neutrality is to prevent this happening in Brazil.

“You have an Internet for the poor, available through a limited mobile network that disrespects net neutrality, only allowing you to post on Facebook. And you have the Internet of the rich, who access the Internet through both the mobile and the fixed network,” says Internet Management Committee’s Lefévre.

This is the third article in a four-part series on Internet access in favelas and urban peripheries in Brazil. Don’t miss parts one and two. For the entire original article in Portuguese by Escola de Jornalismo Énois and data_labe published by Nexo Jornal click here.