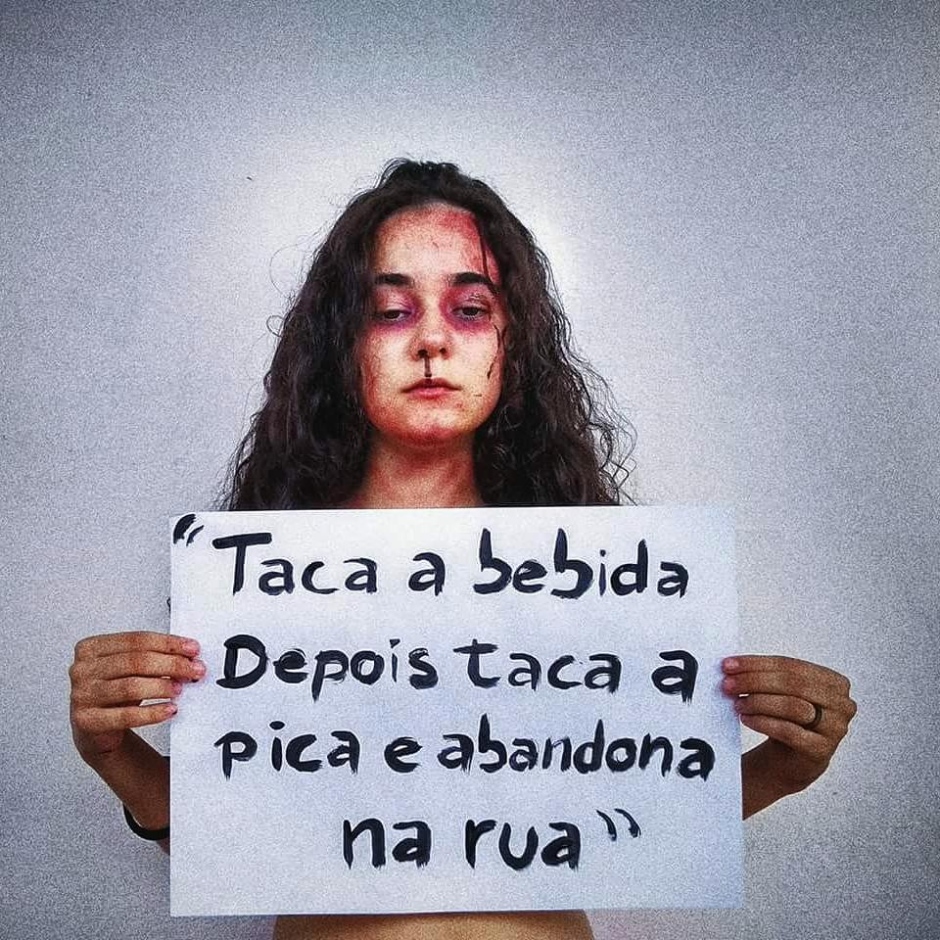

Brazilian music was going well until the release of [funk song] “Só Surubinha de Leve”—translated as “Just a Little Orgy.” The song has generated controversy and a ton of hypocrisy. Many people (famous and anonymous) have protested against the funk lyrics of MC Diguinho, “Get her drunk, **** her and leave her in the street,” which would constitute the sexual assault of a vulnerable girl, asking for the funk artist’s head on a silver platter. I decided to dig deeper into this “suruba” (suruba is also slang for “mess” as well as “orgy”) and bring some important points to the conversation. In addition to what the lyrics say, you need to understand why the song says what it says.

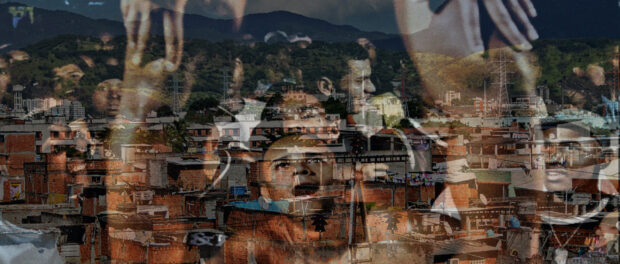

My name is Edilano Cavalcante, I live in the Manguinhos favela in the North Zone of Rio de Janeiro, and I live with the day-to-day reality of a place that is culturally and financially impoverished. Here the “surubinha” happens daily, and it comes in several forms.

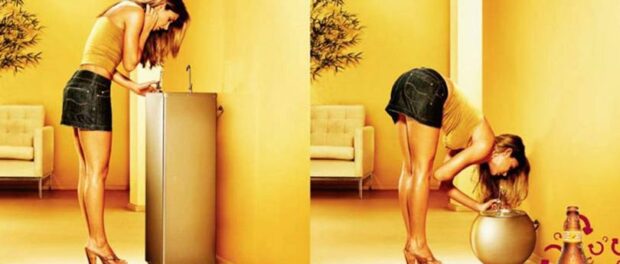

First, it happens on national television, which is beamed into people’s houses daily and exerts a strong influence on popular culture. Across TV programs, soap operas and advertisements, Brazilian TV has a tradition of using the hypersexualized female body as a way to attract viewers and sell products, stimulating its audience to crave the female body, while men are encouraged to see the female body as an object to be used and discarded, or something to be made submissive to their desires. You may think I am talking about a parallel universe, but before you disagree, I would ask you to take a careful look at entertainment programs, TV commercials, your favorite soaps, and watch how women are viewed and presented.

Next there is the Internet that, unlike TV, can take the user to different worlds within seconds. Among those worlds, the ones that get the most people’s attention (not by chance) are the worlds of entertainment and fun. In the “worlds” with the most viewers, guess what is most heavily promoted? The rapid and inexhaustible consumption of products and pleasure. For this, the same technique of hypersexualizing the female body is used. The difference is that on the Internet, everything is allowed. Women are made vulnerable as video clips (both Brazilian and international) are loaded in effect excusing rape and the culture of pleasure above all else. Social media demands explicit images and constant physical beauty, where the display of bodies is the greatest tool for attracting attention. Not to mention the plethora of easily accessible pornographic sites in which the bodies available for use and disposal are predominantly female and young, popularly known as “novinhas” (meaning teenage girls), one of the most searched terms on pornographic websites in Brazil.

It is important, however, to speak of the cultural hypocrisy that the country lives and breathes every day, built on racism, machismo, and slavery. How can we ask that its favela residents, renegade children of the motherland, be inspired to speak of their lives in the same poetry as [composer, singer and musician] Tom Jobim, who practiced his creative pastime on the rooftop of his Ipanema apartment or drinking coconut water on the beachfront? How can we ask the impoverished ghettos to sing about “the beauty of being Brazilian” or about “the girl from Ipanema” on a sunny afternoon?

On the contrary, we are encouraged daily to be macho, to look at the “novinhas” and demand that their bodies be mere instruments of momentary pleasure. If we look at a young woman without this “malice,” we are ridiculed by our peers. Our position as “player” is in doubt. The girls in the favela, on the other hand, are pressured to surrender to the orders of submission and to the search for coveted beauty that is reproduced on TV screens, cell phones, and computers. Their muses are artists, singers, middle-class actresses who, through their social, cultural, and financial means, have greater safety to display their bodies and not be viewed as only objects of consumption, but rather objects of desire.

The distance between social levels determines whether a woman is perceived as a “slut” or a “diva.” For young women in video clips and on TV, glamor. For young women in favelas: “Get her drunk, **** her and leave her in the street,” often left pregnant, with marks of physical and psychological abuse, disrespected and facing a lifetime of trying to survive on the leftover crumbs.

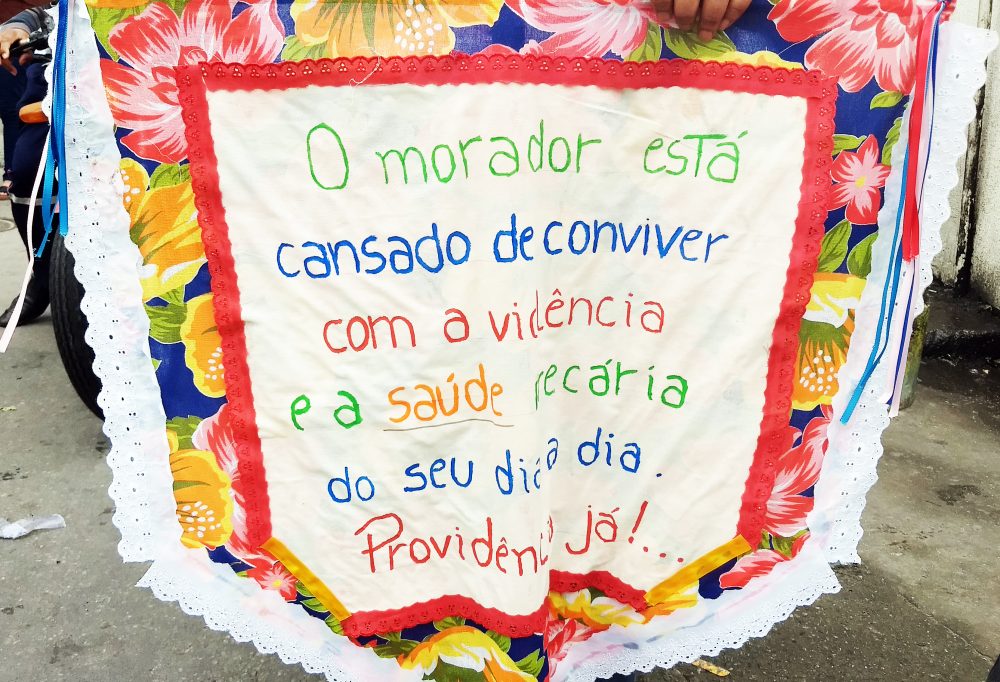

Here in the favelas we are all abandoned. This is not a new denouncement. Every day they deny us a decent job without exploitation, they deny us a quality education, one that will get us into university. They deny us quality public safety, other than black men killing black youth. Every day they deny us the right to basic health, capable of resolving the trauma and symptoms caused by such long-suffering days, as they also deny us culture, sport, and leisure.

And when poetry is written by a woman who states that she is a “malandra”—a word carrying a mix of positive and negative connotations meaning mischievous or a player—she often ends up emphasizing this stereotype by unintentionally saying that the woman likes it. And everyone applauds, the TV and Internet are euphoric, they call her a diva, a queen, a feminist, an independent woman and they emphasize that all girls should be “malandras,” that they should get down low on the dance floor and not let womanizers play them. It is the perfect illusion for maintaining a hypocritical, sexist, homophobic, and cruel society.

It is very easy to blame funk, favelas, and their residents for their unappealing and constant stories of suffering. It is difficult to question why a large part of the population survives on crumbs, while a small percentage live like kings and queens, bestowing on themselves the right to say what is right or wrong.

We don’t want any kind of “surubinha,” neither small nor big. If you don’t either, fight for a more just country, for guaranteeing the rights of the population, especially the poor people of our country. However, if you only spoke out against the song because you’re afraid your son or daughter will end up dancing and singing the lyrics at family lunch, you’re just another selfish hypocrite, disguised as a patriotic defender of good manners.

This article was written by Edilano Cavalcante, a community communicator and resident of Manguinhos.