For the original article in Portuguese by Rithyele Dantas published by Jornalistas Pretas click here.

Last Thursday, June 28, hundreds of people gathered in Cinelândia, downtown Rio, to march on the Court, Legislative Assembly, and Candelária Church, calling for the obvious: for the basic and universal right to life.

Residents of Acari, Complexo do Alemão, Complexo da Maré, Chapadão, and various other favelas brought the full power that favela residents have to the Cinelândia square. The power that comes from body movement, from tone of voice, from the shaky emotion that comes from having to speak for those who have had their lives cut short. The power of those who can muster from their pain the motivation to carry on shouting louder and louder.

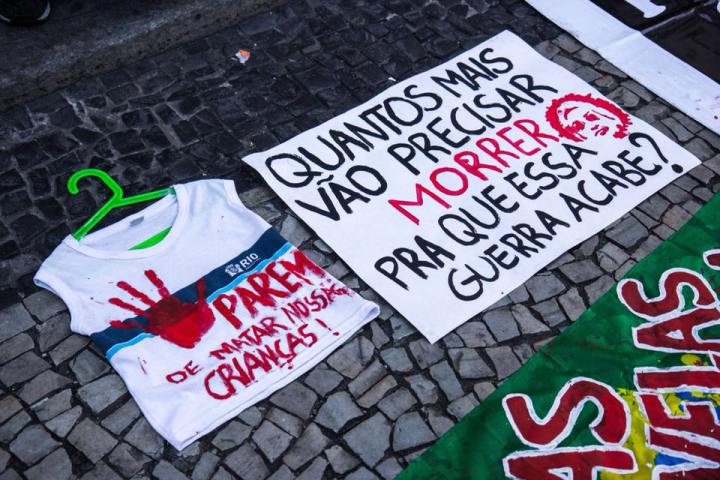

With a cigarette in her hand and a dull, distant look, Bruna Silva is a woman with a thirst to continue until the end. A woman who held up her son’s blood-stained shirt all the way through the protest. Bruna Silva, a woman who chose not to be quiet and not to hide herself away. A woman who decided to expose to the media the crime of a lost young life, the life of Marcos Vinicius da Silva. Bruna Silva, who warmly received each hand extended in support, is the mother of Marcos Vinicius: the boy who was in the wrong place at the wrong time. She’s a mother who misses her son’s voice, his scent, his life. She’s the mother of the boy who was shot dead on the way to school. The boy who asked his mother the question that has reverberated and shaken everyone this week: “Mom, didn’t they see I was wearing my school uniform?” (And rewriting this phrase here was one of the hardest things I’ve had to do in my life.)

Helicopter overhead: take cover if you can!

A helicopter that should only be used to orient police operations is now being used arbitrarily, shooting at random. The “flying tank,” as favela residents have begun to call it, was in action on the day that Marcos Vinicius and six other people—whose names were not divulged—were assassinated. In this hunt, anyone can be shot in the comfort of their own home, while they watch TV or eat lunch with their families.

“It’s a horrible feeling: the helicopter flies low overhead, giving the impression it’s going to land on top of your house… I live on the second floor and it’s really absurd, having to go downstairs to my mom’s house, where the safest place is the tiny bathroom, so we end up with ten people in a tiny bathroom. This is the reality of the favela.” – Renata Souza, Maré resident and member of the Rio State Legislative Assembly’s Human Rights Commission.

Helicopters in action are not a new phenomenon but the debate around this issue has picked up pace this week. According to data from Defezap, an app for denouncing state violence, helicopters fired shots during at least six operations over the course of a year.

In August 2017, a grocer called Tião was shot in the head by a bullet that pierced his market roof in Jacarezinho in Rio’s North Zone, leading to a series of protests against the belligerence of police operations.

The Defezap data also recorded shots coming from police helicopters in Mangueira and Maré, where last week the NGO Redes da Maré counted one hundred bullet marks in the ground. On June 28, residents woke up terrified in Complexo do Lins and Morro dos Macacos, also in the North Zone, because helicopters were shooting there too.

But this is not the first year that helicopters have been firing on favelas. In 2009 a shootout caused a helicopter to crash in Morro dos Macacos, killing three police officers. In late 2012 shocking film footage showed Civil Police chasing one of the city’s most powerful drug traffickers: the “Mathematician.” He was killed in Senador Camará, in Rio’s West Zone. Conversation captured by the footage shows the irresponsibility of the police operation, showing that the police officers’ emotion had taken over all reason. “It looks like him, right?” one police officer said—but it could easily have been someone else.

In 2016 four Military Police officers died when their helicopter crashed during an operation in City of God: afterwards seven people were killed in an act of revenge.

For some, Rio de Janeiro is symbolically in the midst of warfare, but the city is not officially at war. There was never a declaration of an ideological or territorial dispute, so experts in public security consider such actions of war to be unacceptable, putting at risk lives in favelas, putting at risk workers, women, senior citizens, and even children on their way to school.

Mothers against police violence

It’s always striking to see mothers of the movement (and in movement!) at protests against the violations committed by the State, fighting for the lives of young people from favelas and the periphery. Mothers of the young people killed at the rate of one every 23 minutes in Brazil. Mothers who seem to have nothing else to lose and who take the lead at protests, in the struggle. Many Brazilian mothers who’ve had their children taken from their laps, from their houses, have organized together to fight for justice.

“What’s the cheapest meat out there? Black meat! My struggle began when my son was assassinated by the police in Pavão-Pavãozinho. The officer who shot my son had already been involved in 14 autos da resistência [killings allegedly resulting from resistance]. When I got to the hospital they told me that my son had been in a shootout with police, but that’s a lie! People saw what happened but they are scared to tell the judge. Now, thank God, we’re protesting and speaking out.” – Ivanir Mendes dos Santos, activist in the mothers’ network and housing struggle

Bruna Silva, the courageous mother of Marcos Vincius, insisted on showing her son’s blood-stained school shirt to all the media present. Her aim is to get the State to admit that it shot her 14-year-old ‘son: a boy who, according to her, liked the Internet and messing around with his friends, a boy who wanted to live but who had this right taken away.

Silva says that, on the day Marcos Vinicius died, residents of Vila Pinheiro—one of the favelas that makes up Complexo da Maré—were not given advance warning of the police operation. She says it all happened quickly, that the helicopter flew very close over her rooftop. She says there were two armored vehicles on the ground, one by the corner of her house and the other stationed in a nearby alleyway. She says it was the one in the alleyway that shot Marcos Vinicius. Several people all told the same story: residents saw shots fired from the vehicle before it drove away. Before he died Marcos Vinicius said, “It was the tank that shot me, Mom!”

“I sent my son off to school all tidy and they sent him back to me covered in blood. My son asked me a question and now I’ll ask the same question to the State: didn’t they see that my son was wearing his school uniform? I know they saw him, his school bag was fluorescent. This is the shamelessness of our our State.” – Bruna Silva

Silva also has a daughter, Maria Vitória da Silva, in whom she puts all her hope for the future. The 12-year-old also goes to school in Maré and, according to her mother, was totally in shock when she heard about her brother.

“You want to know what Marcos Vinicius was like? Just ask his sister and she’ll tell you everything. There are so many stories!”

Silva is scared for her daughter’s life—“God save me from sending my daughter to school and having her end up like her brother”—but said that she would not stop her daughter from studying at her school and wouldn’t give up living in Maré either.

“This is for my daughter’s life, for the lives of all the kids in Maré… I want the State to assume responsibility, I don’t have to prove anything to anyone. They’re the ones who have to prove themselves to me! Marcos Vinicius’ mother is here and I want to know who shot Marcos Vinicius!”