This is the fourth article in an ongoing series on the Brazilian electoral political scene in 2018.

The multiplicity of political parties in Brazil and their weak ideological cohesion often leads voters to ignore views held by the party itself and instead, vote almost exclusively in favor of candidates with whom they personally identify. This generates what is usually called a “crisis of representation” between voters and parties. This personal identification, in turn, is much more closely linked to agendas of identity than social class. In the past social class was considered the determining factor for both party organizing—reflected in parties such as the Workers’ Cause Party (PCO) and various other workers’ parties—and civil society organizing, whether in trade unions or social movements. Today there seems to be a far greater propensity to vote for the candidate that supports the cause with which voters personally identify (whether that is LGBTQI+, evangelicalism, or small business ownership) rather than an agenda with which they identify as a social class—a trend that that seems to be fueling polarization.

This political party landscape often confuses voters. Here we try to uncover some of the mysteries behind these party dynamics.

Political Parties

The mystery begins with the use of acronyms to identify political parties. Despite parties’ frequent similarities, these acronyms camouflage the politics they represent and become a challenge for voters, especially given the vast number of parties. How many times has the PMDB (Brazilian Democratic Movement Party) been mistaken for the PSDB (Brazilian Social Democracy Party), for example? This doesn’t happen so easily in countries where political parties are identified by name, like the US (Democrats and Republicans) and the UK (Labour, Conservatives, etc.).

Furthermore, capitalizing on voters’ rejection of both “the Left” and “the Right,” the majority of parties currently opt to declare themselves centrists—utilizing terms like “social” and “liberal,” which generates a lot of confusion. Research suggests that Left-leaning Brazilian political parties tend to swing to the right when they are in power. They have to make concessions and alliances with conservative groups to be able to govern, as was the case, to a greater or lesser extent, with the PSDB government of Fernando Henrique Cardoso and Lula’s PT (Worker’s Party).

Current political parties officially came into existence at the end of the dictatorship when the period of re-democratization began. The Constitution of 1988 guaranteed the free creation and dissolution of parties, which resulted in a highly manifold multi-party system—currently with 35 registered parties. While the idea of having many political parties sounds positive in the sense of increasing the chances of representation, in practice, whoever wins the election is forced to make deals with other parties. This inevitably leads to diversions from the party’s proposed course of action, whether in terms of values or ethics.

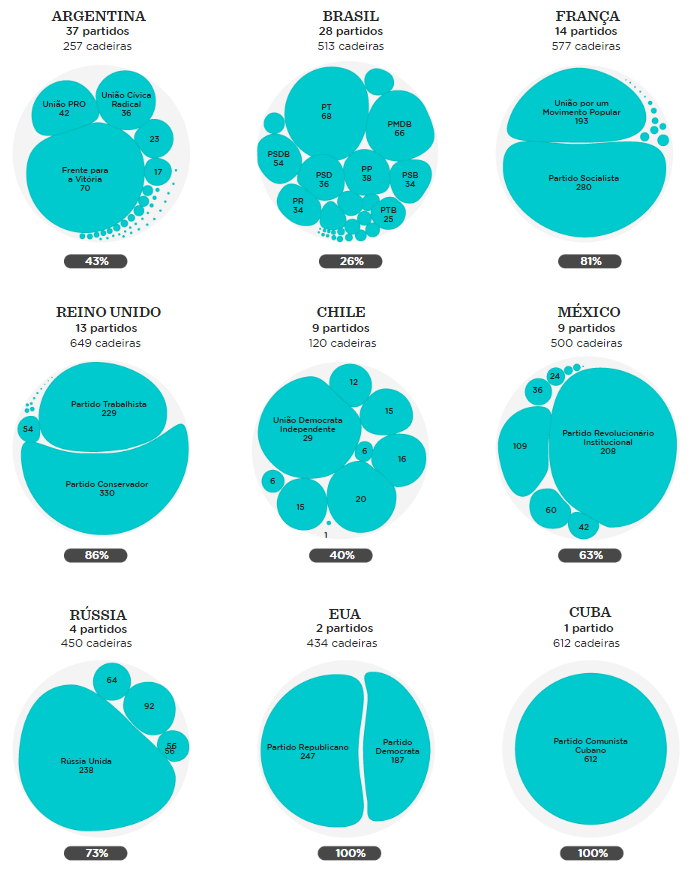

What often happens is the opposite of greater representation: marginalized groups continue to be poorly represented. After all, our Congress is 80% white and male in a country in which half of the population is composed of women and black or multiracial people. Moreover, the political positions defended by various parties end up being strikingly similar. In a study by Nexo that mapped congressional representation in different countries, Brazil was the country with the highest degree of fragmentation (and consequently, the lowest representation by its two dominant parties, as shown by the number in the grey box below the graphic).

This year, the PMDB—officially Brazil’s oldest political party, established during re-democratization in 1981—returned to using its previous acronym from the era in which it was an unregistered opposition party during the military dictatorship: MDB (Brazilian Democratic Movement). This is an attempt to rebrand itself in the face of an image crisis brought on by corruption scandals and the unpopular interim president Michel Temer. This unusual return to the name under which resistance forces (including social movements and trade unions) united against the military regime may be intended to make the party more palatable to the Left.

The youngest of the political parties were founded in 2015: the Sustainability Network, the Party of the Brazilian Woman (PMB), and the New Party. These parties seek to represent a breath of fresh air: Sustainability Network is a term never before used in political party names and denotes a clear environmental agenda, the PMB is the first party alluding to women, and the New Party clearly positions itself as an alternative to age-old politics. This political renovation is also an attempt to attract young people, who correspond to just 2% of the near 18 million people affiliated with some political party in Brazil. The narrative of renovation, however, contradicts the fact that Novo and Rede are the parties with the least female representatives in the country—while the PMB indeed has the highest proportion, reaching 55% at the beginning of this year.

Aside from Novo and Rede, other parties have also opted to distance themselves from the concept of a party by abandoning the “P” in their acronyms, seeking to circumvent the rejection of party politics. Such is the case of Solidarity (SD); Patriot (PATRI); the renewed Democrats (DEM), formerly the Liberal Front Party); and Christian Democracy (DC), formerly the Christian Social Democratic Party. There are also cases of parties that have substituted acronyms for slogans, like Avante (“Onwards”), formerly the Brazilian Labor Party (PTdoB); and Podemos (“We Can”), formerly the National Workers’ Party (PTN). The latter bears no association with the Left-wing Spanish party Podemos—which has been generating homonyms in Latin America—but instead derives from a study in which “podemos” was the most quoted word. Though some of these parties—including the Sustainability Network, the Brazilian Democratic Movement (MDB), Podemos, and Solidarity—define themselves as movements, their emergence diverges from that of parties such as Podemos in Spain and En Marche! in France, both of which arose outside of institutional politics and only later were integrated into the party system. In the Brazilian case, these “movements” were founded as political parties.

This new take on names has helped to set them apart from parties with similar acronyms—such as the Brazilian Labor Party (PTB), the Democratic Labor Party (PDT), the Christian Labor Party (PTC), the Brazilian Labor Renewal Party (PRTB), and, less often, the Workers’ Party (PT). Furthermore, these new names have distanced them from the growing rejection of the Left, symbolized by the term “labor.” Avante’s name change was justified by the party’s president at the time as a way of “strengthening ties between citizens and political institutions” and freeing the party from an old name that “no longer represented its true ideas.” Proof of this came in the last election when both parties supported Aécio Neves of the PSDB, a social democratic party in name, but one that today doesn’t ally itself with Left-wing parties. The rebrandings are not only targeting voters but also candidates elected to Congress, who bring the possibility of television airtime and funding for the party. Podemos, for example, attracted 12 new congresspeople and two senators with their name change.

In addition to previously registered parties, one year prior to the election, there were 70 party creation requests registered at the Superior Electoral Court. A large number of aspiring parties are heralded as conservative, as is the case with the Social Family Party, the Conservative Party, the Party for the Reconstruction of National Order (a reformulation of Enéas Carneiro’s party of the same name). Moreover, the potential return of Arena and the attempted creation of a Military Party are cause for concern. Arena is a conservative party created to rule during the dictatorship when the multiparty system was banned, while the Military Party openly celebrates the dictatorship (one of its speakers said that they want their electoral number 38, alluding to the caliber of a gun, or 64, alluding to the year of the military coup) and wishes to “return to power and invade Congress […] by democratic means.” Moreover, the evocation of specific causes is alarming—as in the case of the Corinthian Party (alluding to a São Paulo soccer team) and the sector-specific political agendas embodied by the Sports Party, Public Security Party, and the National Health Party. Some parties, on the other hand, seem to have been created to try to remedy the lack of political representation available to some groups, such as the National Indigenous Party; Favela Front Brazil; and the Equality Party, which aims to include people with disabilities.

This strategy of creating political parties is partly due to the fact that they automatically receive public funding once approved. They can also acquire television airtime and extra funds very easily if an elected assembly member changes their allegiance to the newly created party, allowing them to assume a featherbedded job or strengthen coalitions with bigger parties, without great changes in terms of representation. For a new party to be created, one of the prerequisites is a large number of signatures from unaffiliated voters. This requirement corresponds to 0.5% of the valid votes for federal Congress in the last election, currently equivalent to nearly 500,000 voters.

This is the fourth article in an ongoing series on the Brazilian electoral political scene in 2018.