In July 2017, federal lawmakers transformed the controversial Provisional Measure 759 into Law 13.465—known as the Land Regularization Law—approving measures that streamline the process of land regularization in urban and rural areas. Favela residents and legal experts have raised serious concerns about the content of the new legislation, with criticism centering on the law’s failure to address the needs of residents and communities at risk of eviction. For many, the law encourages real estate speculation and exacerbates the affordable housing crisis in Rio de Janeiro and other Brazilian cities. This article briefly assesses the Land Regularization Law and its impact on favelas, one year since the reform was enacted.

Law 13.465 has broad impacts because the legislation addresses both urban and rural land regularization. Prior to the enactment of the new law, land use and ownership in cities and the countryside were treated separately, through different legal mechanisms and institutions. In contrast, the new law brings together previously dispersed guidelines for land regularization in a single legal framework. On its surface, the law effectively makes land regularization more efficient, bypassing lengthy judicial proceedings and facilitating adverse possession and land titling processes.

However, the law remains highly controversial. Since its approval, a series of legal challenges have been brought to Brazil’s Federal Supreme Court (STF) on the grounds that aspects of the reform are unconstitutional. Legal proceedings to overturn articles of the law have been initiated by former Prosecutor General Rodrigo Janot in September 2017, lawmakers from the Workers’ Party (PT) in October 2017, and the Brazilian Institute of Architects (IAB) in January 2018. In defense of the law, President Michel Temer’s government responded to these efforts through the Office of the Attorney General (AGU), affirming its constitutionality, highlighting its importance for “rationalizing” land use and promoting the right to property, and claiming that the law advances social rights.

Social movements, as well as housing and land rights advocates, remain critical of the new law. The law facilitates the privatization of occupied public lands, leading critics to label Law 13.465 as the Lei da Grilagem in reference to the historical practice of illegally acquiring public land by falsifying legal documents. In rural areas, this means that farmers who occupy public lands can gain title and ownership. In the Amazon and frontier zones, this mostly benefits large landholders, threatening conservation areas and exacerbating the concentration of land ownership in rural areas. Advocates of agrarian reform and influential social movements like the Landless Workers Movement (MST) have clearly expressed their opposition to the law.

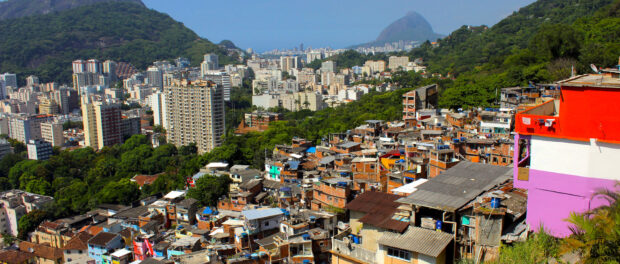

While urban social movements’ demands are different from those advanced by rural movements, they share similar concerns over the Land Regularization Law. In addition to regularizing occupied public land, where many favelas are located, the law facilitates adverse possession and recognizes the direito real de laje—codifying that separate floors of a building with private entrances can be recognized as an independent unit with a separate owner and title from the main building. For many favela residents, these are potential mechanisms to gain land titles and secure the right to remain in their communities. But advocates of affordable housing and access to land worry that privatizing public land will fuel real estate speculation, driving up housing prices and accelerating the process of gentrification.

Rio de Janeiro Public Defender Maria Lúcia de Pontes commented on the impact of the new law in the city, stating: “Currently, it has not facilitated the land regularization process in low-income areas, which have been neglected because of significant real estate speculation in the city in preparation for the mega-events.” Pontes highlighted the role of former Mayor Eduardo Paes‘ administration in enabling these processes. She continued to describe that the law has “reinforced existing difficulties in regularizing low-income areas, especially in favelas, considering that it attributed the [power] to establish and approve the process of land tenure regularization to City authorities—a regression compared to previous legislation.”

For families living in favelas in Rio de Janeiro, land regularization is a point of serious contention. For some, receiving land titles would represent the fulfillment of demands for land tenure security. However, the high cost of living in cities like Rio de Janeiro and the process of gentrification makes others wary of the perceived benefits of property titles. Professor Rafael Soares Gonçalves from the Department of Social Service at the Pontifical Catholic University (PUC-Rio) believes that the government has lost legitimacy, worsening the relationship between low-income residents and local government, and reducing demands for creating and improving government programs. Gonçalves noted that in this context, “land regularization policies in Rio de Janeiro have been empty.”

Over the past year, according to government data and media reports, it appears the Land Regularization Law has increased the rate of titling in rural areas in Brazil. The urban context remains more complex, as the responsibility for regularization falls upon municipal governments, which have varying political, technical, and fiscal capacities. In Rio de Janeiro, the city’s recent history of regularization and evictions has demonstrated that establishing and approving the process of land regularization is closely tied to the real estate development interests and the tourism industry. By streamlining the process of regularization for delivering individual property titles, the Land Regularization Law may help individual residents gain property rights. As such, the Land Regularization Law has tilted the scales further towards individual private ownership and away from the social function of land stipulated in Article 184 of the Brazilian Constitution. In doing so, the legislation fails to embrace alternative models of regularization that may better address the needs of favela residents by guaranteeing permanent affordability.

Ezra Spira-Cohen is a PhD candidate in Political Science. His research is on the impacts of land policy and state intervention in land tenure in Brazil.