On Friday, August 3, the Parliamentary Front Against Removals, Evictions, and the Violation of the Right to Housing hosted a public debate entitled “Housing Rights and the Fight Against Evictions” at City Hall. With over fifty people in attendance—including activists from favelas across the city—the debate sought to call attention to communities currently facing eviction and strengthen communication between favela residents, social movements, and City authorities.

City Councilor Renato Cinco, who organized the event, opened the debate by discussing Rio’s long history of evictions and arguing that Marcelo Crivella‘s mayoral administration has only served to exacerbate the situation of favelas facing eviction. Since Crivella’s inauguration, the City has introduced several proposals and initiatives that may facilitate evictions, including establishing a goal to remove houses located in areas of high environmental risk and creating a working group to address matters of “resettlement” for families living in “irregular occupations.”

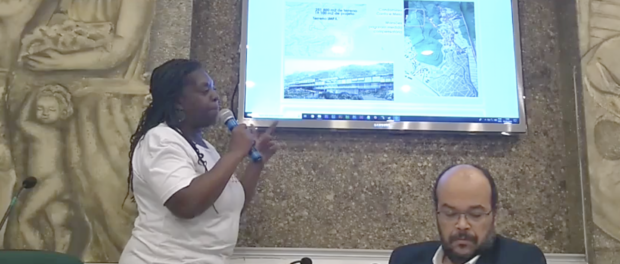

The first panelist to speak was Emilia de Souza—resident of Horto, former president of the Horto Residents and Friends Association (AMAHOR), and member of the Popular Council. Souza spoke about the reality of working-class people and favela residents in Rio, noting: “Communities have been criminalized, evicted, excluded, and forbidden to live in the South Zone due to real estate speculation. This is the story of Rio de Janeiro.” Following her speech, Souza shared a visual presentation, highlighting several communities’ struggles in the face of forced evictions, environmental injustice, and the restriction of public services—while also voicing residents’ demands and recognizing their victories.

Resident of Vila Autódromo Maria da Penha carried on the conversation noting that her community has not been respected—despite the collective rehousing agreement negotiated by those community members who resisted eviction and ultimately won the right to remain. “I am outraged that City authorities, having signed an agreement with twenty families, are not respecting [us]. Two years have passed and nothing has been done,” Penha stated. She argued that the City’s failure to fulfill its promises represents yet another strategy to evict the remaining residents.

Adriana Bevilaqua, a representative from the Public Defenders Land and Housing Nucleus (NUTH) joined the conversation by noting that it is the government’s obligation to provide adequate housing for all. However, this right has not been fulfilled because there are very few measures that work to guard against evictions, she suggested. As a result, in the pre-Olympic period between 2009 and 2015, 22,059 families (an estimated 77,000 individuals) were evicted from their homes in Rio de Janeiro.

Drawing upon Bevilaqua’s words, Maria de Lourdes “Lurdinha” Lopes Fonseca from the National Movement for the Fight for Housing (MNLM) argued that there must be new tools and avenues to address evictions and reverse the speculative logic that increasingly characterizes the city.

Following these speakers, Verônica Cristina de Oliveira—representing the Municipal Sub-Secretary for Housing—shared a few words about the current housing situation in Rio de Janeiro. Oliveira’s speech mostly revolved around clarifying the purpose of “resettlement.” She noted that the resettlement process seeks to conserve preexisting organizational structures within communities and that the process is carried out in a participatory manner. Furthermore, Oliveira stated that families will only be resettled when they are impacted by specific conditions, such as environmental risk. She argued that the process is transparent and that through resettlement, the City seeks to rehouse families near their original community rather than displacing them to precarious areas.

Following Oliveira’s speech, residents of various favelas were invited to express their concerns and demands. Marcello Deodoro of Indiana Tijuca in the North Zone expressed strong criticism of City authorities, specifically Mayor Marcelo Crivella, stating that many residents in his community still lack basic services and struggle to cover the rising cost of housing. Antônio Cardoso from Rio das Pedras in the West Zone, whose community won a major victory in the fight against evictions in late 2017, highlighted the emotional and psychological costs of evictions.

Edivalma “Di” Souza da Cunha, representing the communities of Maracajás and Rádio Sonda in the North Zone, noted that the two small communities are extremely vulnerable when confronted with eviction threats. It’s difficult for public defenders to support residents in their times of need due to the strict entry regulations at the Air Force base, which restricts access to these communities. Ana Frimerman from Araçatiba in the West Zone noted that her community has reached out to the City for support in their battle against eviction by federal authorities, but the City has failed to facilitate or make provisions to support their case. Another resident emphasized the indignation of favela residents who lack land tenure security: “How can it be that we cannot be the owners of our own houses, but that foreigners can? How outrageous!”

After listening to each community representative speak, Oliveira responded, defending the City’s resettlement process. She noted: “When speaking of intervention, I’m not talking about intervention in terms of evictions, but intervention in terms of upgrading.” Oliveira continued: “It’s important to think about resettlement as a potential for upgrading and advancing a community, and not a question of eviction or resettlement.” She asserted that there are processes in place for communities to engage in a participatory manner during the resettlement process.

Closing the debate, other speakers emphasized that the City has to date failed to dialogue with communities undergoing or threatened by eviction and that promises to communities have not been delivered. Mobilizing through the Parliamentary Front Against Evictions, residents of favelas across Rio hope that the City government will open spaces for dialogue to address these concerns and collectively ensure their right to housing.