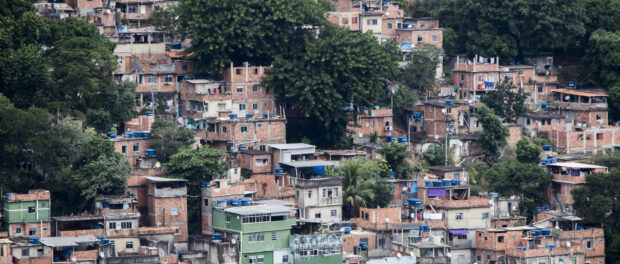

This is the first article in a four-part series on the potential to apply the Community Land Trust (CLT) model under existing Brazilian laws to secure land rights in Brazil’s favelas. The series was written for a Brazilian audience and summarizes and adapts a report by lawyer and urban planner Tarcyla Fidalgo, prepared with the support of the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy (LILP). It clarifies several aspects of the proposal, showing the foundations of the CLT model; adapting the model to favelas; and explaining its benefits, applicability, and ways of functioning. In this first part, we contextualize the topic and develop a panoramic view of the Community Land Trust model as an urban policy instrument for favelas.

The publication of this series follows five days of workshops (from August 23-27) with a delegation from Puerto Rico, whose members successfully implemented a CLT in eight informal settlements along the Caño Martín Peña in San Juan with excellent results. The workshops were carried out by Catalytic Communities* in partnership with the Rio de Janeiro State Public Defender’s Office, Pastoral de Favelas, the Architecture and Urbanism Council of Rio de Janeiro (CAU/RJ), and the Laboratory for Studies of Transformations in Brazilian Urban Law (LEDUB).

The Origins and Foundations of the Community Land Trust Model

The Community Land Trust model arose in rural Georgia in the 1960s spearheaded by champions of civil rights. However, the first urban Community Land Trust was only implemented in 1980, in the city of Cincinnati. Since then, the model has been widely disseminated with hundreds of diverse experiences around the world, including in Canada, England, Scotland, Australia, and Kenya.

The traditional Community Land Trust does not anticipate its direct applicability in informal settlements. However, as a highly flexible model capable of being adapted to different contexts and needs—developed precisely to protect communities vulnerable to the speculative real estate market—the CLT model has become an instrument of interest to attend to the demand for tenure security in favelas. This is because the main objective of this model is to provide long-term affordable housing—combating land speculation and guaranteeing residents’ tenure security.

The translation of Community Land Trust to Termo Territorial Coletivo (“Collective Territorial Agreement”) in Portuguese seeks to value the idea of an agreement between various parties–a sense of collectivity in managing a common territory, and is due to the lack of a Brazilian term to describe the legal instrument constituted by a trust. Through a Community Land Trust, the land is owned by the CLT (a legal person), which is composed of residents and a collectively governed council. However, while the community establishes an agreement for the use of the territory where residents live, the buildings themselves—the properties located on CLT land—are individually owned, allowing for a healthy coexistence between individual and collective interests.

Over the past decade, Rio de Janeiro has endured a range of urban policies linked to the context of the mega-events hosted in the city, contributing to a series of both forced evictions and urban land speculation in favelas. For example, the Pacifying Police Unit (UPP) program had a clear impact on the speculative potential of the favelas in which it was implemented. Property prices rose in nearby formal neighborhoods, as well as in the favelas that received this intervention—primarily those located in the South Zone, the city’s most touristic area.

In this context, it has become necessary to think of new mechanisms and instruments that could guarantee residents’ permanence in their communities, whether that means guarding against the risk of eviction by the government or by the land market. Property titles—communities’ traditional goal—reduce the threat of eviction by the authorities. Even so, they do not offer full protection—as seen in the case of Vila Autódromo. However, titles actually exacerbate the risk of market evictions (gentrification), both because of the legal recognition of real estate transactions with land values included, and due to the individualization produced when a market-based logic that accompanies individual titling is introduced to the community, transforming homes into commodities.

As a result, with titling it becomes all the more essential to develop methods of strengthening community bonds and local organizing. Thankfully, the CLT also offers an effective structure for this, facilitating the social cohesion necessary to handle future disputes.

Community Land Trusts as Potential Urban Policy

The Community Land Trust (CLT) is an instrument that brings together legal, social, and urban planning dimensions with the objective of offering affordable housing for perpetuity, which in the context of informal settlements means its focus is to guarantee residents’ permanence in their neighborhoods, regardless of the speculative (and thus threatening) nature of the surrounding land market. This is possible because when constituted, the CLT, whose council is elected solely by residents, becomes the owner of the land. Residents thus govern the land which has been withdrawn from the market. The land is separated from the value of buildings which can be bought and sold. Thus, the land is not subject to speculation. During its creation, the CLT can opt to establish a price ceiling for property sales to guarantee even greater housing affordability.

While the ideal scenario would involve the approval of specific enabling legislation for Community Land Trusts, one of the primary benefits of this model is that the instrument can be applied through existing urban policy frameworks. Although government support can facilitate the process, it is not a requirement for the creation of a CLT. Thus, a CLT can be created anywhere where land rights are being secured as an alternative regularization policy, or as an add-on instrument by residents themselves.

The Fundamentals of the Model

Beyond providing quality affordable housing, the principal objective of a Community Land Trust is to guarantee residents’ tenure security. However, this type of housing can be organized in different ways and will depend on the CLT’s own structure.

Furthermore, CLTs can extend beyond housing per se, contributing to local development more broadly—for example, by developing community gardens and local businesses and demanding the implementation of public services. The range of possibilities is enormous as local development will depend on the needs and wishes that the council and its participants decide to address. However, while it is a very flexible model, this tool has some basic characteristics common to all forms:

In general, Community Land Trusts seek to:

- Guarantee access to land and security against eviction for the poorest populations that are most vulnerable to pressures of the real estate market;

- Collectively manage the lands registered within the CLT framework, while the homes built on these lands remain individually owned;

- Allow for the self-organization of residents and maintain partnerships with professionals on an ongoing basis, as a form of managing the CLT;

- Offer voluntary entry, since no one is obligated to take part in a CLT.

When applied in favelas—functioning in areas that are already socially and culturally occupied—the model allows for local development to occur in accordance with local interests and culture. The community leads and drives local development. This is an essential element for meeting local needs and promoting the engagement and organization needed to open doors to further projects and improvements. In addition, as more CLTs are formed, the organized social momentum for demanding rights increases. CLTs can unite to create larger movements, articulating demands for other rights and organizing around other causes.

Greater Security Against Evictions

Forced eviction is a form of social, psychological, physical, political, and economic violence. Beyond violating residents’ rights, forced evictions also result in the loss of everything they have built over time. Psychological, social, and economic rebuilding is not always possible.

Once the CLT is designated as the landowner, security in the face of an eviction process increases dramatically. Property titles are not individual and the very function of the CLT implies the self-organization of residents, together with professionals. As such, beyond requiring an attempt to evict the entire community at once—something that already hinders government action—the CLT’s professional council increases the technical support and broader network base during a possible eviction attempt.

This is the first article in a four-part series.

*RioOnWatch is a project of the NGO Catalytic Communities