This is the seventh article in an ongoing series on the Brazilian electoral political scene in 2018.

Distinct from political reform movements and alternative candidates aiming to transform the (inevitably partisan) traditional political system from within, the current elections have also seen the proliferation of civil society and academic initiatives intended to assess candidates’ policy proposals and monitor their implementation once the elections take place. These initiatives have been driven by new technologies and the increasing impact of social and virtual networks on public opinion.

To Find Your “Match” and Choose a Candidate

One example in Rio de Janeiro is Rio as a Whole, a non-partisan movement spearheaded by Casa Fluminense and the Intelligent Citizenship Foundation. The initiative works to increase citizen participation in the electoral process, promote transparency, and foster social control over public administration with the overall aim of increasing opportunities and reducing inequality. Beyond gathering proposals from civil society on issues such as reducing violence, job creation and income generation and access to basic services—including sanitation, health care, and education—which comprise the Rio Agenda 2030, Rio as a Whole has launched a digital platform where political candidates can commit to proposals registered by civil society organizations and supported by citizens. Simultaneously, users prioritize the proposals on the platform so that they are “matched” with candidates whose commitments are most closely aligned with their priorities. At the time of this article’s publication, more than 200 citizen proposals have been submitted, over 90 organizations have created proposals, 166 candidates have committed to the proposals, and almost 900 individual users have registered on the platform. After the elections, the platform will continue to be available online so that people can verify the proposals that successful candidates committed to and monitor their implementation.

Another matching platform is TemMeuVoto.com (“You’veGotMyVote.com”), which operates on a national level for candidates running for the positions of state representative, federal Congress, and senator. Different from Rio as a Whole, the platform doesn’t generate a match after candidates commit to civil society proposals but rather once the user responds to six questions related to candidates’ ideas and policies. The questions include candidates’ integrity, their positions on the economy and social welfare, and their priority issues. Once complete, the platform presents the ten candidates most aligned with the user’s answers to inform their choice, along with details about those candidates’ parties, their biographies, and past lawsuits or convictions (if applicable). It’s important to note that the platform only considers the proposals of candidates who actively choose to sign up, which means that any results are restricted to those candidates (who represent approximately 10% of all candidates). The platform is run by members of political reform movements that were mentioned earlier in this series, as well as members of political education organizations such as Politicize.

VozAtiva.org (“ActiveVoice.org”) also performs a matching function based on questions answered by users but focuses exclusively on candidates running for federal Congress across Brazil. The difference is that the questions ask users to position themselves for or against ten statements per topic (environment, human rights, economy, integrity and transparency, and miscellaneous). Again, this site only includes candidates who sign up. The platform was created by thirty civil society organizations that work in the areas of human rights, integrity and transparency, climate, and social impact enterprises for a new economy. These organizations include the Institute for Socioeconomic Studies (INESC); the Group of Institutes, Foundations, and Enterprises (GIFE); the Ethos Institute; Transparency International; Engajamundo; and the Institute for Climate and Society. Following the elections, the platform will remain available to monitor the actions of those elected compared to the positions documented on the platform.

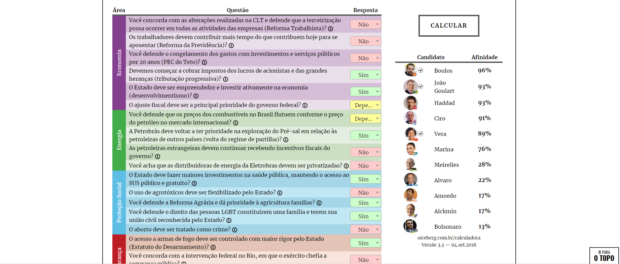

The Political Affinity Calculator (for presidential candidates) and the Partisan Affinity Calculator (for defining positions along party lines, which helps in voting for representatives and senators) similarly match users with candidates and parties based on responses to questions on topics such as education, security, social protection, the economy, energy, and democracy. Who Represents Me? is another site that calculates users’ alignment with presidential candidates and parties, as well as incumbent federal deputies, through a list of questions. Finally, there’s PolitiQuem (“Politician Who?”), a collaborative platform that allows users to view and compare candidates’ positions on issues such as drug policy, LGBTI rights, labor law reform, the legalization of abortion, and the bearing of arms to provide guidance on the selection of a presidential candidate.

To Ensure Greater Representativeness

The site #MeRepresenta (#TheyRepresentMe) brings together candidates from all parties and for all political offices who are committed to the agendas of politically marginalized groups such as members of the LGBTQ+ community, Afro-Brazilians, women, and residents of urban peripheries. The platform allows users to filter all candidates registered on the site by state, party, race, gender, and political issue. These issues include police demilitarization, housing, affirmative action and quotas for women in the legislature, and combating violence against women. The objective is to bring these underrepresented groups closer to the political system and elect candidates who are committed to their causes and to strengthening a transparent and participatory democracy. The platform was set up in 2016 to help people choose city council candidates across the country, reaching one million views and 150,000 users. This year, #MeRepresenta is also seeking to fight against hate speech and discriminatory language used by candidates, as well as the fraudulent practice by which parties run fictional female candidates (especially black women from low-income backgrounds with low levels of education) in order to get around legal requirements to field a certain quota of female candidates. Among the organizations behind #MeRepresenta are Blogueiras Negras (“Black Women Bloggers”), the Intelligent Citizenship Foundation, the Feminist Lawyers Network (DeFEMde), and #VoteLGBT.

The Mapa das Minas (“Women’s Map”) brings together female candidates in Rio de Janeiro, presented on a map by political office, municipality, and region of the city. Users can filter results by several feminist issues and by party. Another site is Black Women Decide by Umunna—a network of black women who want to discuss institutional politics and get involved in the electoral debate. Umunna means “sisterhood” in Igbo, a language spoken in Nigeria, the place of origin of a large percentage of historically enslaved people who were brought to Brazil. The Black Women Decide platform produces and shares data about black female candidates, such as the proportion of [public] campaign funds that they receive (2.5%) and their chances of being elected (1.6%). The site also deconstructs falsehoods about black women in politics, such as the idea that black women only win elections with votes from regions inhabited by white elites, or the idea that black women aren’t capable of holding positions of power. The aim is to incentivize black women to participate in the political debate and in institutional politics.

To Investigate Your Candidate

The platform Publique-se (“Publish It”), an initiative of the Brazilian Association of Investigative Journalism (ABRAJI), allows users to search for candidates’ names in hundreds of thousands of cases of the Brazilian Supreme Court (STF) and the Superior Court of Justice (STJ). The platform not only generates cases in which candidates have been accused or are under investigation but also all instances in which their names were mentioned in legal proceedings, such to inform voters and journalists about candidates’ conduct.

Hereditary Candidates allows users to see which families have two or more members involved in politics in order to denounce the lack of change and diversity in Brazilian politics. According to the platform, there have already been more than 300 federal deputies elected to Brazil’s Congress for whom politics is a family business. This is the case of Marco Antônio Cabral—son of Sérgio Cabral (former governor of Rio de Janeiro, currently serving a 14 year sentence for corruption and money laundering), cousin of Aécio Neves (senator for the State of Minas Gerais) and Francisco Dornelles (vice-governor of Rio de Janeiro), and grandnephew of Tancredo Neves (former president-elect and prime minister). Marco Antônio Cabral is seeking re-election as a federal deputy in Rio this year.

The Politician Record Detector app—created by the Complain Here Institute, which has a well-known customer complaint platform—performs facial recognition through photos (from leaflets, TV commercials, rallies, etc.) to detect any criminal trials, cases of administrative misconduct, and investigations involving the politician in question. Complain Here also launched a plugin called Keep Watch Here. Once downloaded, on any website that the user browses, the plugin highlights (in purple) the names of politicians who have held office and are involved in ongoing legal proceedings. Hovering the mouse over a name, it’s possible to see the record of the politician in question. Currently, Complain Here and Keep Watch Here only cover the current and former president and incumbent federal deputies, senators, and governors. As such, these apps cannot yet be used for all candidates in the 2018 elections.

To Fact-Check and Fight Fake News

Finally, there are sites and platforms for fact-checking, the subject of the first article in this series. These sites almost immediately comb through information shared online by candidates checking for dubious claims and facts. In addition to Agência Lupa, To the Facts, Lie Detector by Meu Rio, and Truco by Agência Pública—all of which have been active since the 2016 elections and were mentioned in an earlier article—there’s also Project Proof, created by a network of partners from mainstream media outlets and from To the Facts. In addition, there are other sites that are not limited to political fact-checking, such as Fact or Fake? (by G1), Is That Right? (by O Globo), and UOL Verifies.

Furthermore, two highly innovative fact-checking sites stand out. The first is #TiraTeimaSobreDrogas (#DropTheFearAboutDrugs)—a fact-checking mechanism created by the Center for Security and Citizenship Studies (CESeC) in partnership with the Laboratory of Interdisciplinary Studies on Psychoactive Drugs (LEIPSI)—which specifically checks statements made by presidential candidates regarding drug policies. The second site is Checazap, which specifically checks content shared on WhatsApp groups. This site is run by the data journalism project Data_Lab and the journalism school Énois. Checazap’s fact-checkers are young people from the peripheries of Rio and São Paulo. It’s often more challenging than fact-checking on other platforms because of the private nature of WhatsApp groups and the speed by which WhatsApp messages are shared, especially in work or family WhatsApp groups. Checazap’s results are shared weekly with subscribers via WhatsApp itself, as well as on CBN and HuffPost Brasil.

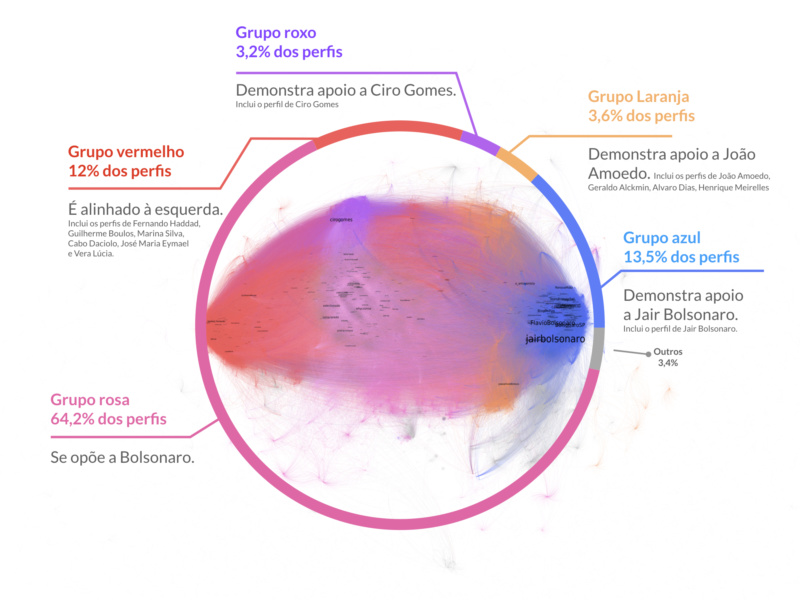

There’s also the Digital Democracy Forum – #Observa2018—an initiative of the Department of Public Policy Analysis at the Getúlio Vargas Foundation (FGV)—which monitors election races, including public debate and the impact of fake news on social media in the current elections. The platform produces analyses that range from measuring the flux of mentions of candidates on social networks in real time, to measuring how many of these mentions are generated by automated Internet robots and which pieces of information in circulation are false.

You’re the Target is a plugin that allows users to see which campaigns are directly targeting him or her on Facebook with political advertising such as boosted posts. These tactics have recently become regulated and are permitted by new electoral rules, so long as advertising is done through the profile of the candidate or party. Users can also see which of their preferences motivated the campaign to target them. The aim is to increase transparency around the use of these tactics on social media during elections.

You’re the Target is a plugin that allows users to see which campaigns are directly targeting him or her on Facebook with political advertising such as boosted posts. These tactics have recently become regulated and are permitted by new electoral rules, so long as advertising is done through the profile of the candidate or party. Users can also see which of their preferences motivated the campaign to target them. The aim is to increase transparency around the use of these tactics on social media during elections.

Finally, Elections Without Trickery, created by the Criminal Justice Network, aims to share accurate information with users about issues of security and justice. The site has a mechanism to automatically send questions on these issues to candidates selected by users so that voters can be more discerning when it comes to promises made by candidates (which are often impossible to fulfill) and better decide how to cast their votes.

This is the seventh article in an ongoing series on the Brazilian electoral political scene in 2018.