On Tuesday, November 13, national, state, and municipal forces undertook the first forced eviction in Rio de Janeiro since the pre-Olympic Games era—when Mayor Eduardo Paes oversaw the removal of tens of thousands of families from their homes. The federal Air Force, state Military Police, and Municipal Guard worked in tandem to remove six families from the community of Maracajás on Ilha do Governador, close to Rio’s International Airport in the North Zone. The eviction came approximately one year after the community faced its first major eviction threat, which left residents in a constant state of fear.

While the eviction appears to have followed a court order, there were several irregularities in the case and several violations were committed in the process. To further understand the implications of such a terrifying event, in this article, we present an overview of what Brazilian law says about eviction and housing rights and examine how these actions hold up against international human rights treaties.

Legal Interpretation of the Case

First and foremost, it is necessary to address the legal irregularities surrounding the case. The eviction took place following a court order issued in September 2017—one that residents claim was subsequently negated, leading to at least a temporary stay on evictions. In spite of this, Air Force officials claim to have followed the law in carrying out the eviction order, affirming that residents were adequately notified—an allegation that residents deny.

Aside from the legality of the order, Maria Júlia Miranda, coordinator of the State Public Defender’s Office’s Land and Housing Nucleus (NUTH), says that the way in which the judiciary is interpreting the case is even more troubling. She wonders how the courts can define families residing in an area for almost 100 years—decades before the Air Force even acquired the land—as illegal “occupiers.”

“What I think is sad is that the judiciary doesn’t analyze the case more closely; [the courts] take legal precedents and apply them automatically, without concretely analyzing the case at hand. They don’t examine the specifics and verify that in the case of Maracajás, it wasn’t a recent land possession. There was no [legal] way to evict [residents]—they treat them as merely criminal. They aren’t able to step outside of the case, away from the documents, and get to know the reality,” Miranda lamented.

Legal experts recognize the difficulty of defending communities’ right to permanence in court in the face of eviction orders, particularly when the federal government is involved. At a meeting held months prior in another community in Rio facing eviction threats, one lawyer mentioned that federal judges rarely rule in favor of communities in such cases. This is not only a restrictive understanding of law and legal precedent but also an obstruction of residents’ constitutional rights, potentially leading to international human rights violations.

Brazilian Law

To fully understand how these actions represent grave threats to the rule of law, it is important to understand the specific details of the eviction order. However, the Air Force did not release justification for evicting residents, also declining to state the purpose for which the expropriated land would be used—facts per se that are arguably unlawful. Residents and supporters have reason to believe that the land will be used for one of two purposes: to be sold to Rede D’Or (the largest private hospital group in Brazil) or to be used in the privatization and expansion of Rio’s International Airport. In either case, activists and community members believe that the land is being seized by the government to benefit private interests.

As such, the eviction in Maracajás, through the lens of Brazilian housing law, stands in direct opposition to Articles 5 and 6 of the Brazilian Constitution. In Article 5, clauses 22 and 23 provide that land must perform a social function, which has been interpreted to mean that property should work for the greater good of the public. In other words, wealth should be distributed rather than concentrated. Clauses 24 and 25 allow the government to take land for “public necessity,” or when it presents a danger to the public. Article 6 solidifies the right to adequate housing.

If, in fact, the intention is to sell the land on which the community of Maracajás stands, or pass it on to a private entity, this would constitute an egregious breach of residents’ constitutional rights. Miranda had this to say: “This property belonged to the federal government and was passed on to the Air Force at some point in time. It seems that the intention is to construct a private hospital there… evicting people that are living there so that it can be used for another function. This is exploitation by the Air Force with profit in mind. I defend that property fulfilling the social function of housing should be protected to the detriment of property that fails to perform a social function.”

While the land in question is situated in the federal domain, since municipal forces were directly involved in the action, we can also look to Rio de Janeiro’s Municipal Organic Law of 1990 for more clarity on local housing law. Article 12 prioritizes housing rights for children and the elderly, while Article 422 reaffirms that land should perform a social function. Perhaps even more important is Article 429, which states that residents must not be removed unless there is a direct physical risk. Moreover, it requires that residents receive technical assistance throughout the negotiation process and states that if residents are, in fact, removed, they must be relocated nearby.

Local and federal authorities failed to respect these laws in evicting residents from Maracajás.

International Human Rights Violations

When it comes to human rights violations, we need not look further than the eviction process. Security forces surrounded the area in the early morning hours such to barricade residents inside and keep any assistance out, and journalists were barred from entering the street in front of the houses—all leading to a slew of human rights violations at the hands of national, state, and local forces.

“They entered our houses as though we were armed criminals, hitting us and using pepper spray. My 65-year-old father was shoved to the ground and hit his head on a rock. My 95-year-old grandmother was kicked out of the place that she has lived for her entire life,” stated Leonardo Pereira, a resident of Maracajás and graduate of both the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ) and State University of Rio de Janeiro (UERJ). “My neighbor suffered the onset of a heart attack, another cut his hand deeply after being aggressively provoked by soldiers and police officers. Both of them are elderly. What they did to us was barbaric.”

In the middle of the chaos, residents texted out information to local activists. Inside the houses were several elderly individuals, at least some of whom required attention from Air Force medics. There were also around seven children present at the time. One resident left the area in tears in the middle of the occurrence (police officers let her leave with her toddler). Many (if not most) people had been sprayed with pepper spray, many were beaten with police batons or thrown to the ground, and several suffered violence-related or stress-related accidents.

This violence is not only horrific but also constitutes a violation of international human rights treaties to which Brazil is a signatory. According to the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR): “The obligation of States to refrain from, and protect against, forced evictions from home(s) and land arises from several international legal instruments including the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (art. 11, para. 1), the Convention on the Rights of the Child (art. 27, para. 3), the non-discrimination provisions found in article 14, paragraph 2 (h), of the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women, and article 5 (e) of the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination.”

Furthermore, through Resolution 1993/77, the OHCHR deemed that “practice of forced eviction constitutes a gross violation of human rights, in particular, the right to adequate housing.” To guarantee the fulfillment of this right, the UN has published guidelines authored by the Special Rapporteur on adequate housing on what should and should not happen before, during, and after evictions—in cases where they must take place.

The following is a brief summary of these procedures: before an eviction, there should be “appropriate notice, effective dissemination, public review and public hearings, provision of legal, technical advice.” “Evictions should not result in individuals being rendered homeless or vulnerable to the violations of other human rights.” During an eviction, “neutral observers, including regional and international, should be allowed access upon request,” and “states and their agents must…ensure that no one is subject to…acts of violence.” After an eviction, “at a minimum, authorities shall ensure that evicted persons…have safe and secure access to…basic shelter and housing.”

Nearly all of these guidelines were ignored in evicting families from Maracajás.

Implications

So, what does all this mean? Several themes emerge. First, it is important to address the legal interpretation and application of the law in this case, particularly given the common application of a double-standard in land regularization. Current president Michel Temer’s recent land regularization law (13.465/2017) is a prime example of this phenomenon, easing the process of regularizing public land occupied by individuals and halting all legal action against the person in question while the request is pending. Agrarian reform movements have expressed strong opposition to the law as it favors certain groups—facilitating the transfer of federal land to large landowners, particularly in rural parts of the country.

In reference to Temer’s law, public defender Maria Júlia Miranda commented: “In reality, it’s a law that affirms the possibility of land titling in public areas—but it doesn’t require government entities to carry out titling when properties are consolidated. This is what the judiciary understands: it could be done.” Maracajás residents had already requested that the community be titled, without any response from relevant government agencies. Law 13.465 theoretically would allow for Maracajás residents to receive titles, at least halting evictions until a response is provided. Rather than complying with this request and initiating the regularization process, another interpretation was adopted by authorities: considering residents as occupiers and therefore criminal.

Finally—and perhaps even more troubling—is the timing of the eviction. According to Miranda, this is the first forced eviction case since the pre-Olympic Games era. Mayor Crivella has threatened communities with eviction, yet has only demolished houses that were unoccupied. This case, with blatant human rights violations, resembles cases of eviction effected under Mayor Eduardo Paes, which could signal a slippery slope. “Since I arrived here, I have not seen any eviction with the use of physical force. We are in a moment that is politically very delicate, with a tendency to increasingly criminalize land occupations. This is clear rhetoric of the criminalization of urban and rural communities and settlements. When you determine that a court-ordered eviction must take place and security agents have already been saturated with the rhetoric that these occupations are criminal, there is a tendency to use increasing physical force each time. I think this is dangerous,” stated Miranda.

The six evicted families have been staying with family and friends until they are able to find housing, as government officials only offered beds in city shelters to the evictees.

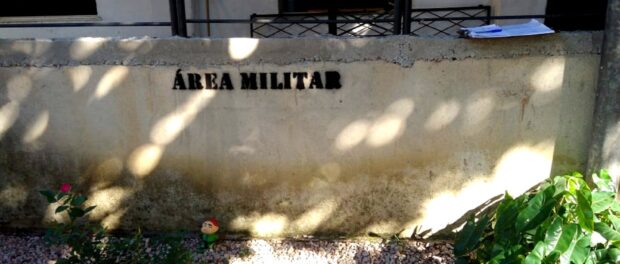

According to residents, as of November 26, Thales Arcoverde Treiger of the Federal Public Defender’s Office has obtained an injunction that will permit the evicted families to return to their homes. When residents return, they will find their houses still intact—now spray painted to show Air Force ownership—but empty, as they were forced to remove all of their belongings during the eviction.

While this is potentially an important victory, the community remains uncertain and vulnerable to future eviction attempts. Beyond Maracajás, thousands of families across Rio are at risk of forced eviction. It is imperative that public authorities comply with international treaties and national, state, and municipal law. Constitutional protections exist for each and every Brazilian, not just a select group. In the face of rights violations, it is everyone’s duty to stay vigilant and stand in solidarity with threatened communities to guarantee that rights are upheld.