For the original article in Portuguese by Joel Luiz Costa published by The Intercept Brasil click here.

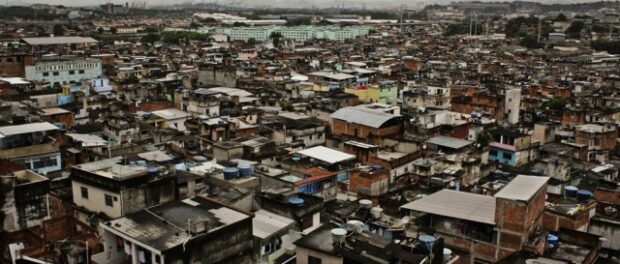

I was born in Jacarezinho, a favela in Rio’s North Zone, and raised there by my grandmother until the age of six. Out of 126 neighborhoods in Rio de Janeiro, Jacarezinho ranked 121st in the city’s Human Development Index. My mother was a domestic worker for a rich family and whenever I think of my childhood, I remember her talking about the difficulties of working “in madame’s house” and bringing home stale bread at the end of the day. My father worked at the Nova América Textile Factory in Rio’s North Zone, which later became the Nova América Shopping Mall, famous for its outlet stores. He then worked as a contractor for Petrobras, Brazil’s state-run oil company. I don’t know what his job was at Petrobras, but I do remember the photo of him wearing the company uniform that he proudly showed off.

There are some childhood memories that I remember by overhearing people talking about them, but those stopped when I was about eight years old. From then on, I can clearly remember what happened. When I was eight, we went to live in the north of Rio de Janeiro state. Moving to a new city and a new life was partly an effort on behalf of my parents to improve our family’s security, but it was also about improving access to school and work—both of which were made more difficult living in a favela with its daily routine of police operations, shootouts, school closures, and difficulty of coming and going.

My parents always dedicated themselves to their children’s studies and their lives revolved around this goal. In much the same way as Nem da Rocinha got into drug trafficking to raise money to pay for his daughter’s medical treatment, my father also got involved in the drug trade to help his family. He wanted his children to be able to study and have access to opportunities and a decent lifestyle—something that he and my mother didn’t have for themselves.

Since early childhood, my father nagged me about studying. At the first sign of a bad grade on my report card, he banned me from playing video games and going to soccer practice. He made me read the sports newspaper out loud to him, day after day—reading newspapers is a habit that I still have to this day thanks to him. Bad behavior at school was not tolerated, neither were absences or detentions. He said that in our house the average grade was going to be 90, not 60.

When I became a teenager, my father started to talk about me studying law. He wanted to be the father of a police chief. The actual job didn’t seem to matter. What he really wanted was to have a son with a profession worthy of a title—a credential proving that you’re a winner in life.

Imagine how that would feel for a man who earned a living in the underworld of the drug trade—to be able to take his son out of the favela and put him in one of the most important institutions in the country. This would essentially mean defeating the exclusion that the system imposes upon us. As for me, I was impressed by police detectives in American films and let myself get carried away—I ended up liking my father’s idea. I admit that I started law school, living in the interior of the state of Rio de Janeiro, with my eyes already on the prize of working for the Federal Police.

Like any good law student, I came to realize over the course of my studies that things aren’t always as they appear and that the university admissions process in this country has become an industry—one that is increasingly elite. However, studying law became my passion.

I can’t remember when I first heard my father say, “When Joel graduates I’ll leave the drug trade,” but I do remember him saying it over and over again during the second half of my studies. It was clear that he was only in the drug trade in order to see his son get a degree—“A black boy becoming a professional.” My future graduation seemed like a turning point in his life when everything that he had done and sacrificed would finally make sense. It would be the proof that all of that time spent in a business that some people demonized and that other people thought necessary was not in vain and that finally, the ends justified the means.

The reality is that the favela has its own social structure in that drug dealers have money, power, and social status. And let’s be honest: life in a capitalist system, whether you’re living up in the favela or down in the formal city, revolves around the desire for those three things: power, status, and money. Without the family structure that I had growing up, maybe I would have found it hard not to turn to this “shortcut” myself. As Racionais MC’s said in the 1990s: “Time to think, do you want to stop—what do you want? To live just a little bit like a king, or a long time as a nobody?”

Ever since I heard this song when I was 12, I thought that living a little bit like a king would make much more sense, since, after all, you only live once.

People from the “asphalt” (formal city) have the idea that everyone involved in the drug trade is a drug kingpin like Fernandinho Beira-Mar or Pablo Escobar. I recommend reading Orlando Zaconne’s book about drug dealers called Acionistas do Nada (“Shareholders in Nothing”).

In entering the drug trade, my father’s aim was simple: to create and allow for educational and employment opportunities that, according to the “legal” rules of the exclusionary capitalist system, were nearly impossible to acquire by a poor black boy from the favela. How many lawyers do you know who are from favelas? Or judges? Or prosecutors? The justice system is white, elitist, and classist. How can you talk about hard work and meritocracy to a guy who has four siblings, who at the age of six already lived at a boarding school, and who has never told me any story from his life in which his father was at home? In my 29 years of life, I have never heard anything about my grandfather on my father’s side. When you don’t even have the minimum of family structure, you’re literally starting from zero.

It might be difficult to explain this to someone whose first job was a six-hour-a-day internship at the age of 22, spending their salary on vodka and designer clothes instead of worrying about paying the bills, but yes: poor people do sometimes resort to the drug trade as a way to survive. They do it to put food on the table for themselves or their families or to achieve a minimum level of social and financial dignity faced with the exclusion that our capitalist, consumerist society brings.

When I got my law degree at 22 years of age, my father exploded with happiness. He bought so many tickets to the graduation ceremony that he was able to invite all of my friends from Jacarezinho and there were still some tickets left to sell at the university. He hired a van to take people to the ceremony and suits for my friends to wear. It was a high point in his life.

A few months later, he said goodbye to his illegal life in the favela and went through a process of resocialization—going back to the life of a person with a bank account, living by the rules, taking jobs with formal work contracts, and volunteering.

Don’t think of him as some kind of “criminal genius” who got away with his crimes, unpunished by the government. There’s a hidden figure in the gap between the crimes that the government knows about and punishes through the law and the universe of other crimes committed every day in this country. The truth is that many, many crimes go unnoticed by the government.

Let’s be honest, in the days I spent writing this essay, I’m sure that you and I both committed a crime of some sort and that the crime will go unpunished. My father only saw the drug trade as a source of income that would allow him to fulfill his desire and need to raise his children far away from the cruel reality of public insecurity in Rio’s favelas—a reality that takes away many lives and dreams every day.

After I graduated, I started a graduate program in criminology. Beyond my passion for the subject, it was also a chance for me to be of service to black people from favelas like me. Beyond taking our lives, the government reaches us by depriving us of our freedom—you only have to look at incarceration rates to see this. We have the third largest prison population in the world, with approximately 726,000 inmates.

One of my childhood friends was recently unjustly arrested during a mega-operation by police in the region of Jacaré, Manguinhos, Mandela, and Benfica. My friend lives in a housing project called Bairro Carioca—often called a favela itself, having been largely abandoned by the government. The police raided the housing project and entered his house. It’s a nice house with ceramic tiles on the outside walls and air-conditioning—which led the police officers, conditioned by their racism and ignorance, to assume that the house belonged to a drug trafficker.

The police searched every corner of the house. After failing to find anything illegal, they focused on some bank deposit receipts that my friend kept in a drawer. Each receipt was for an amount between R$5,000-15,000 (US$1,250-3750). Lacking any “better” proof than the receipts to prove their theory that he was a drug dealer, they took him to the police station under the accusation of being affiliated with the drug trade.

This story becomes even more shocking when we notice how important facts about the suspect were relativized by the police. Often the law looks first at the person who committed the crime, rather than starting with the crime itself. For example, my friend has worked as a motorcycle taxi driver for the same company for seven years, with a formal work contract. He owns a motorcycle worth around R$7,000 (US$1750) and also has a car, purchased through an installment plan. At the time, he was renting the house in Bairro Carioca from his mother-in-law, who owned the property. The bank deposits were to his mother-in-law’s account, not his own, which she confirmed at the police station. The money came from the sale of a house, being paid in installments. He was making the payments by bank transfer to avoid carrying money and risk being robbed while working as a motorcycle taxi driver.

None of these details were enough. My friend was arrested at the police station under the accusation of being affiliated with the drug trade—taking a working man who owed nothing to society away from his wife and two young children. He was arrested thanks to simple prejudice, racism, and the need to deliver in front of that whole circus of 3,500 armed civil servants employed to fight the schizophrenic war on drugs—which is, in fact, a war on poor people.

The next day, there was a hearing where we repeated everything we had already said to prove my friend’s innocence and we managed to get him released. Two months later he was absolved of all the fictitious allegations.

When I told this story on Twitter, some people commented that my father had raised me to become a “servant of the drug trade.” What a joke! First, what my father really wanted was for me to apply for a job in the civil service and become another one of those tie-wearing bureaucrats. Second, I really had to fight my parents in order to get them to accept my decision to become a criminal lawyer in the first place.

My father used to tell his friends that I was allowed to do anything I wanted—aside from defending “criminals.” How ironic that that’s what I ended up doing. But thanks to the opportunities that he created for me with what was available to him, he was able to understand over time that my dream was to be a criminal lawyer in order to bring visibility to the debate about how selective and racist the criminal justice system is, beyond the dichotomy of good versus evil. Through the visibility of my work, I wanted to show that I wasn’t representing criminals, but rather a group of people that have been marginalized.