In the 2018 Brazilian general election, voters elected officials at the federal and state levels (president, federal deputies, senators, governors, and state deputies). Among the state deputies elected in Rio de Janeiro are Dani Monteiro, a social sciences student; Renata Souza, who holds a doctorate in communication; and Monica Francisco, a social scientist—all of whom were former advisors to Marielle Franco, the Rio city councilor assassinated on March 14, 2018. Within their mandates, all three women are prioritizing issues concerning violence against women, the genocide of the black population, and affirmative action policies.

How Does the Rio de Janeiro State Legislative Assembly Work?

The Rio de Janeiro State Legislative Assembly (ALERJ) is composed of seventy representatives from numerous parties and aims to represent diverse segments of the population in the legislature. To exercise transparency and civic participation, the majority of its sessions are open to the public.

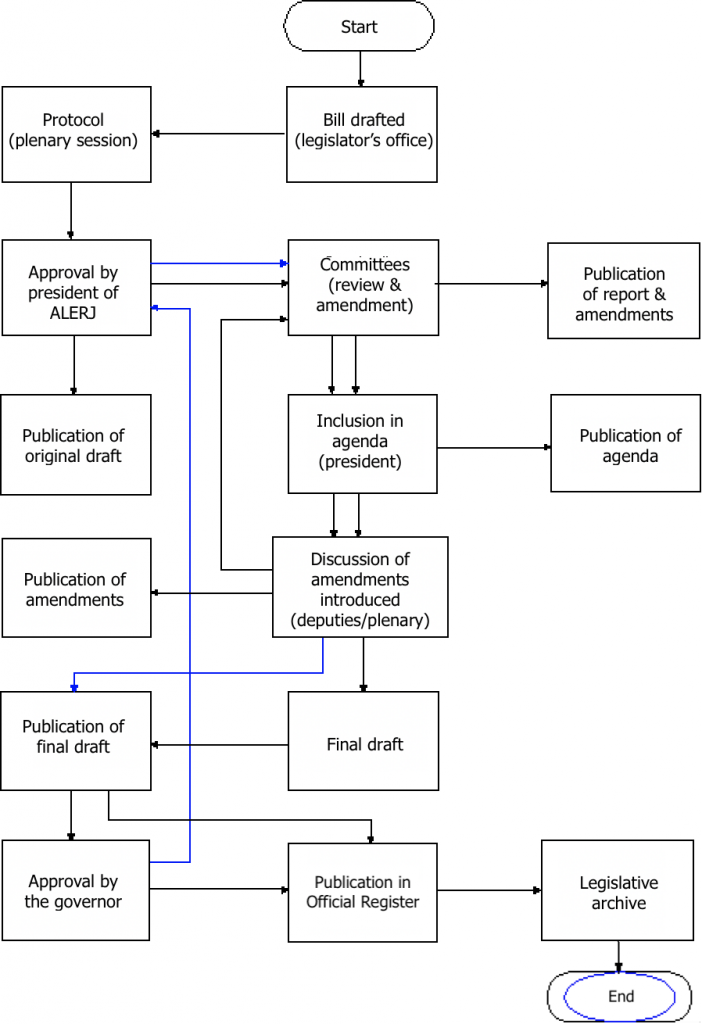

These sessions are held to debate bills proposed by representatives, initiatives proposed by civil society, and legislative proposals by the executive branch, the judicial branch, and the Public Prosecutor’s Office, and to vote on the content of new laws and state legislation. The process of getting a bill approved is not exactly simple: it is discussed in a plenary session and subject to amendments, which are analyzed by committees thematically related to the issue at hand before a vote is held. For a bill to pass, it is necessary for an absolute majority of the legislature (36 representatives) to vote in favor of approval. Thereafter, congressionally approved legislation is subject to full or partial approval or veto by the state executive branch. The state legislature can then uphold or override the veto by a majority vote.

Additionally, state representatives are responsible for approving the state budget and government spending, assuming a regulatory role by overseeing the use of public funds via the State Court of Auditors (TCE), standing committees (the Constitution and Justice Committee, Human Rights and Citizenship Commission, and the Public Security and Police Affairs Committee are among the legislature’s twenty standing committees), special committees (temporarily established for specific purposes), and investigative Parliamentary Commissions of Inquiry (CPIs) for investigating matters of public interest. Representative committees are formed for the purpose of representing the legislature in external affairs.

Women in ALERJ

During their campaigns, elected state representatives Dani Monteiro, Renata Souza, and Monica Francisco emphasized their concern for issues related to the black population, particularly with regard to education, affirmative action and university completion, public security, access to culture, feminism, and religious diversity.

For Monteiro, it was a great victory for three black women from favelas from the Socialism and Liberty Party (PSOL) to be elected to office as state representatives: “In Brazil, it is quite recent to place women in these positions, as democratic spaces were not [intended] for this population.”

Even so, only 17.1% of newly elected state representatives are women (twelve deputies—three more than the number elected last term). “It’s important for this representation to align with [political] agendas focused on machismo, misogyny, racism, sexism, and violence against women—above all, black women,” Francisco adds.

Priority Issues

One issue on Monteiro’s agenda concerns access to public universities and dropout prevention: “The State University of Rio de Janeiro (UERJ) is emblematic: on the one hand, it’s the pioneer of [affirmative action] quota laws. On the other, it systematically suffers from disinvestment and a lack of resources.” For her, as an UERJ student, “the challenge for youth who have access [to universities] via quotas is fighting for educational continuity, for quality instruction based on the three pillars of higher education—teaching, research, and community-based learning—and for the exercise of critical thought and research that generates benefits for society.” She also addressed other branches of UERJ in need of attention, such as the Open University for Senior Citizens (UnATI), the Pedro Ernesto University Hospital, and the Piquet Carneiro Clinic.

Francisco has focused on continuing with Marielle Franco’s agenda through the creation of birthing centers, the ongoing campaign against sexual assault and violence in the municipality of Rio de Janeiro, and the creation of a special office to assist female victims of violence. Furthermore, she values activism, the defense of human rights, the right to live, housing rights, and local community development. One of her ideas pertains to the creation of a training center within the legislature that would “prioritize the participation of women and black people in order to increase the representation of this segment of the population in the legislative and executive branches.” The School of the Rio de Janeiro State Legislative Assembly (ELERJ) currently exists, offering training programs and technical courses for ALERJ public servants.

During the campaign, Souza supported seven proposals from the Rio as a Whole platform, some of which were included in the Rio Agenda 2030, such as “reducing violent deaths, with a focus on the Baixada Fluminense,” “bringing commuter trains up to par with the metro system,” and “approving metropolitan governance in ALERJ.” She is also an activist who advocates for affirmative action policies and fights for the end of the genocide of black and peripheral populations.

Monteiro believes that debates on issues related to inadequate public policies and budget priorities in these areas will be more consistent and more powerful when raised by “those who have truly experienced this disinvestment—those who need to use the Unified Health System (SUS), Family Clinics, and public schools, among other public services” and that her term will be a space for dialogue and development in collaboration with social movements and the local population. Monteiro and Francisco emphasize the importance of maintaining close contact with social movements, “amplifying political action and dialogue,” as Francisco highlights.

Main Challenges for the Coming Years

Nevertheless, the current situation is quite complex and challenging in light of the election of conservative candidates at both the federal and state level. For Francisco, the most important thing is that PSOL, as a party, is united in order to responsibly partake in the opposition on the basis of dialogue and respect—values that are fundamental to the legislature—while remaining consistent in everyday responsibilities.

One concern is that “despite being democratically elected, [some politicians] walk a fine line between democracy and fascism as their way of seeing and doing politics aims to exterminate a segment of the population,” as Monteiro puts it. This tendency is exemplified by statements made by Wilson Witzel—the newly elected governor of Rio de Janeiro who supports the extinction of the State Security Secretariat and wants to encourage “shooting criminals,” even in the absence of legislation backing these sorts of actions.

Furthermore, Monteiro points to the “historic genocide that still permeates the lives of the black population“—in addition to the mass incarceration of a predominantly black male population and the absence of effective public policies to address this issue—as one of the structural difficulties in resolving this situation. In Francisco’s words: “We are totally against policies of violence and the erosion of rights; we will also fight against religious fundamentalism and seek to preserve the separation of church and state.”

To conclude, Monteiro invites “more people to follow the work of ALERJ—electing women who organize around [these issues] has been fundamental.”

Composition of ALERJ

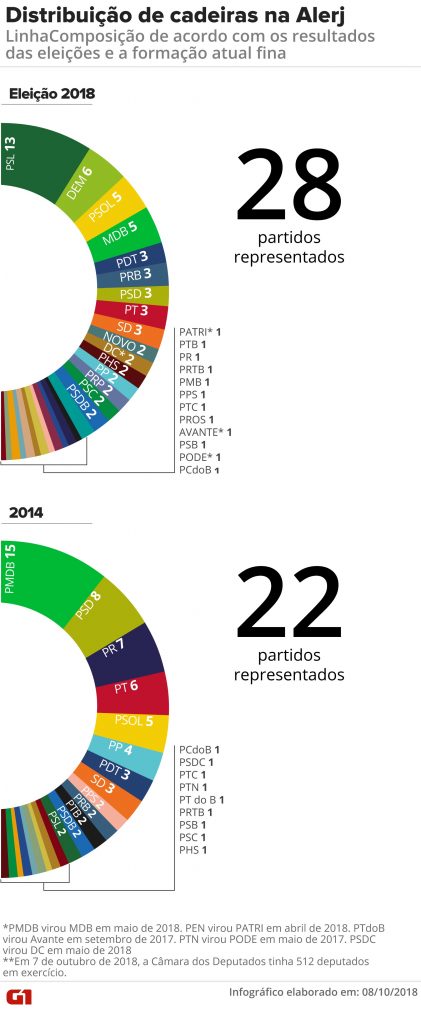

The infographic below compares the party representation during the 2015-2019 and 2019-2023 terms. The figure reveals a great deal about the changes that have taken place with regard to the current political context in Brazil.

With the swearing-in of incoming representatives who are set to take office tomorrow, February 1, 2019, possible alliances and prospects for the election of the president of ALERJ (Brazil’s equivalent of the State Speaker of the House) have begun to emerge. Incumbent ALERJ president André Ceciliano (Workers’ Party–PT) has already formally launched his candidacy (presumably with the PSOL’s support). Re-elected representative André Corrêa of the Democrats (DEM) party has also confirmed his candidacy (despite having been arrested in an operation along with four other incumbent state representatives who also gained re-election for the 2019-2023 term). Amid uncertainties, the Novo party represented by Chicão Bulhões has formed an alliance with the Social Liberty Party (PSL) of Jair Bolsonaro to launch a bid for the presidency. Additionally, leadership positions in internal committees are being disputed—especially the Human Rights and Citizenship Commission, which has been headed by the PSOL for the past ten years.