This is the third article in a four-part series highlighting research that demonstrates the unequal geographic distribution of violence against women in the context of pre-Olympic evictions in the city of Rio de Janeiro.

Violence against women is a structural mechanism that functions as a policy of control with the objective of keeping women in a disadvantaged and systemically unequal position in society. Violence legitimized by the devaluation of women reproduces patriarchal dominance through intimidation, strengthening a pattern of behavior that begins in the home and reverberates in the streets. As demonstrated in the previous articles in this series, territorial isolation and, consequentially, the difficulty of gaining access to the legal system and services, compound the abuses committed in areas dominated by organized crime.

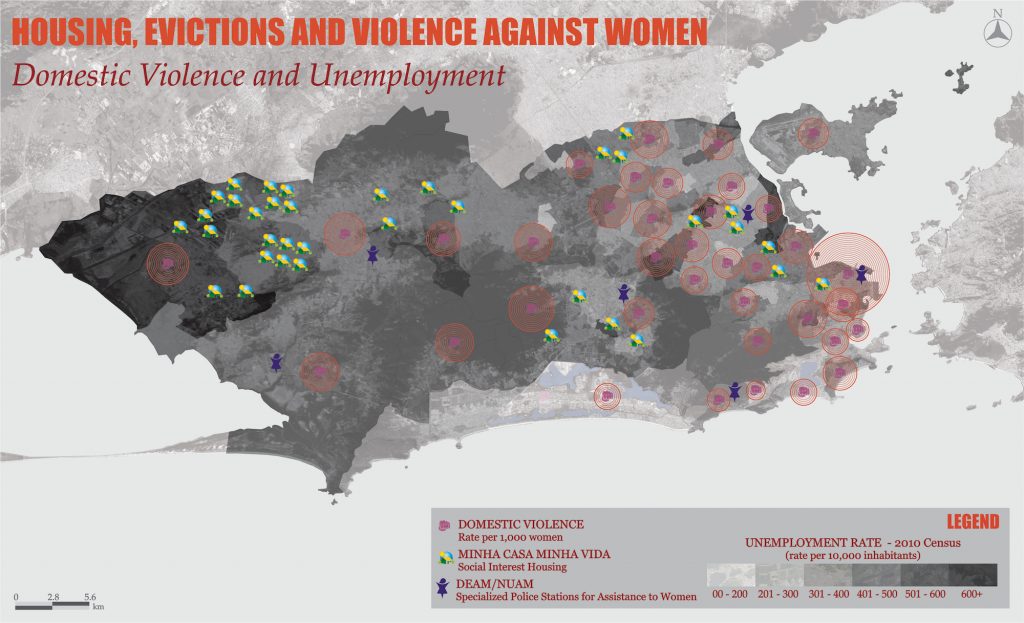

Beyond the context of generalized social violence, the vulnerability that fuels this cycle of violence is influenced by factors such as financial dependence, alcohol or drug use, and unemployment. The map below shows the possible correlation between unemployment and violence against women in Rio de Janeiro.

A distinctive geographic distribution becomes evident when victims’ race is considered, as the percentage of victims of intentional bodily injury who are black or brown is significantly higher in the West Zone (as demonstrated in the table below). Intentional bodily injury, a general category that predominantly results from domestic or family violence, typically takes place in the home. This pattern of violence clearly appears in the West Zone of the city [where the bulk of public housing has been built in recent years] and is less evident in other areas in Rio de Janeiro, thus demonstrating that urban policies—in particular, those related to land use—are capable of modifying patterns of violence.

Table 1: Characteristics of incidents of intentional bodily injuries by zone. Table created by the author.

| ZONE | RACE* | LOCATION* | AGE* | |||||

| White | Black | Brown | Home | Public Space | Child | Teenager | Adult | |

| West | 43% | 13% | 42% | 62% | 34% | 3% | 7% | 88% |

| North | 49% | 14% | 36% | 56% | 39% | 3% | 7% | 89% |

| Central | 55% | 12% | 31% | 34% | 59% | 2% | 5% | 91% |

| South | 63% | 10% | 24% | 47% | 47% | 2% | 5% | 91% |

| *Race, location, and age were not specified in all reported cases. For this reason, the percentages do not total 100% | ||||||||

Here, it is important to once again highlight the difference between data presented in absolute numbers and in rates. The absolute numbers show the number of incidents of violence against women reported in a given area without considering other variables. The calculation of rates shows how many women have been victims of violence in relation to the female population residing in a given area—in other words, the rate considers the population as a variable in order to understand the phenomenon. As already explained in previous articles, the datedness of the 2010 Census in addition to the major urban transformations that have taken place since then make it impossible to calculate estimates for the female population by Integrated Public Security District (CISP) for the entire period analyzed. Therefore, the calculation by rate is presented only for the year 2010 in order to understand the correlation between the data.

As such, similar to the incidence of rape, when considered in absolute numbers, the West Zone is the area that concentrates the highest number of incidents of intentional bodily injury, while the rate per 10,000 women in 2010 is higher in Central Rio.

Table 2: Intentional bodily injury in Rio de Janeiro by zone in absolute numbers (2009-2016) and by rate per 10,000 women (2010). Table created by the author.

| % Absolute Numbers – 2009-2016 | |||

| West Zone | North Zone | South Zone | Central |

| 53.4% | 35.4% | 7.3% | 3.9% |

| Rate per 10,000 Women – 2010 Census | |||

| West Zone | North Zone | South Zone | Central |

| 67.28 | 49.07 | 40.23 | 142.0 |

The term “femicide” has been disseminated and strategically employed by feminist activists and researchers since the 1990s and progressively incorporated as a type of crime in the legislation of various Latin American countries. This process has revealed the discriminatory nature of the invisibility and the systematic oppression of women that promotes impunity in these types of crimes, highlighting government neglect as a factor underlying the persistence of violence against women. In this context, it is important to note that intimate partner femicide often puts a tragic end to a cycle of violence that is legitimized by society and the media through the expression “crime of passion.”

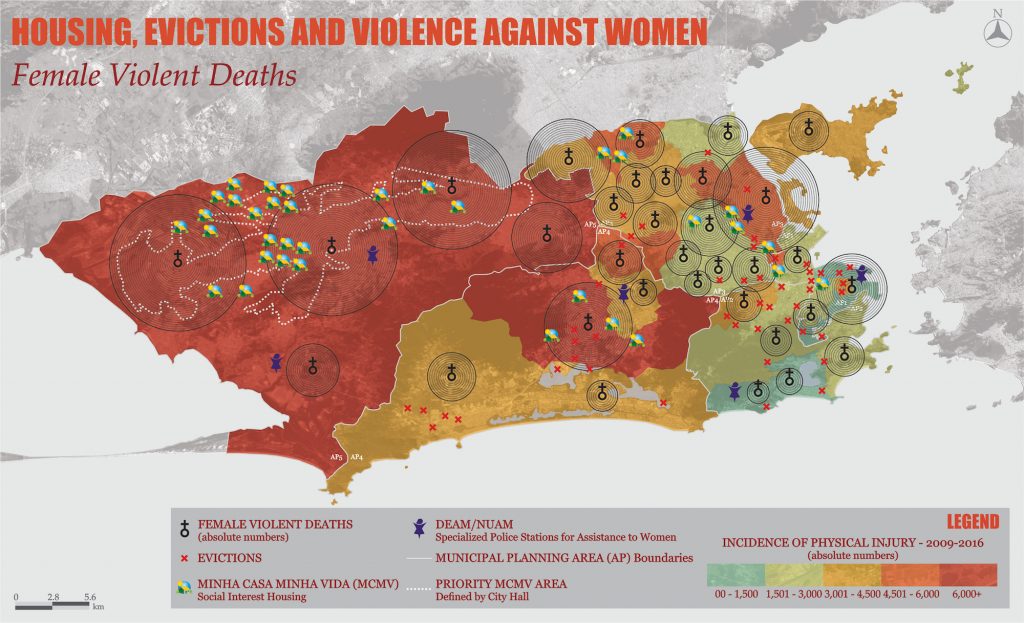

Therefore, there is a correlation between the geographic areas in which women are subject to more abuse and violence and those in which more femicides occur (as shown in the figure above). In this sense, it is important for public policies to be designed in an integrated and multidisciplinary manner, incorporating public safety in the formulation of other types of policies. In cases of violent female deaths, segregating and racist geographic patterns are once again evident in relation to victims’ race (as shown in the table below).

Table 3: Characteristics of violent death incidents by zone. Table created by the author.

| ZONE | RACE* | LOCATION* | AGE* | |||||

| White | Black | Brown | Home | Public Space | Child | Teenager | Adult | |

| West | 28% | 16% | 50% | 31% | 48% | 4% | 5% | 66% |

| North | 33% | 1% | 42% | 32% | 49% | 5% | 5% | 62% |

| Central | 48% | 7% | 31% | 31% | 45% | 7% | 0% | 71% |

| South | 48% | 7% | 45% | 41% | 50% | 7% | 5% | 79% |

| *Race, location, and age were not specified in all reported cases. For this reason, the percentages do not total 100%. | ||||||||

With regard to this type of crime, an important consideration is that the quality of information collected in the [wealthier] South Zone is higher than it is in other regions of the city given that there is a lower percentage of missing information on details of the crime. This may reflect negligence in the documentation of incidents in other regions of the city as a result of socio-economic discrimination.

The criminal impunity that is characteristic of female violent deaths provides that as a violation of the rule of law, femicide is a state crime, considering that authorities fail to fulfill their duties. As such, in the context of generalized violence on various levels, to what point has execution ceased to be a temporary suspension of the rule of law and become the rule—further rendering vulnerable women experiencing a daily reality in which the denial of their rights is a permanent and structural feature of the patriarchy?

Complete Series: Violence Against Women in the Context of Rio’s Pre-Olympic Evictions

Part 1: Introduction

Part 2: Violence as a Policy of Control

Part 3: Domestic Violence and Femicide

Part 4: Institutional Sexism in a Patriarchal City