For the original article by Victor Domingues in Portuguese published in Observatório de Favelas click here.

According to estimates by the São Paulo Civil Defense, one person died and 300 were left homeless in the fire that swept through the Moinho favela on Monday, September 17. It was the seventh favela fire in the city of São Paulo in the last 40 days, and the 34th this year.

On September 3, another fire destroyed nearly 40% of the Sonia Ribeiro favela – known as Piolho Hill – which occupied an area of 12,000 square meters. The Civil Defense estimated that 1,440 people lost their homes in the fire. Prosecutors at the São Paulo bureau of GAECO (Special Assistance Group for Fighting Organized Crime) are investigating whether the fire could have been set deliberately by a group with criminal intent, such as a representative of real estate interests in the region. There is some suspicion that a number of this year’s fires may have been acts of arson, aiming to facilitate the removal of the favelas, thus clearing the way for new development – since legal removals are complicated procedures that can drag on for years.

It’s important to remember that, ironically, Piolho Hill had been considered a “laboratory” for the development of the São Paulo Fire Prevention Program. The program was created by Mayor Gilberto Kassab’s administration and launched in March of 2011. Of the 1,632 favelas in the city, the fifty communities thought to be at highest risk were chosen to participate.

In March of 2012, the Municipal Chamber created a Parliamentary Inquiry Commission (CPI) to investigate the enormous number of fires occurring in the city and to look into the possibility of arson. Raquel Rolnik is an urban planner, professor in the department of Architecture and Urban Planning at the University of São Paulo, and United Nations Special Rapporteur for the Right to Adequate Housing. In an article in her blog, she writes, “It’s awfully strange that favelas that used to be in much more precarious situations, more at risk of fire than they are today – when shacks were made of wood, for example – are catching fire now, during one of the biggest booms in the São Paulo real estate market.”

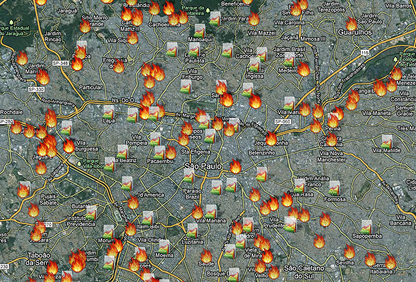

Comparing research data on the fires with information on real estate speculation, it is not difficult to conclude that many of the favelas that have burned in the last few months are located in areas where the value of real estate has increased. Meanwhile, areas containing more favelas are the least valuable — and surprisingly, these areas have had the least fires.

Journalist Patricia Cornils has found the number of police investigations to be tiny compared to the number of fires. “The documents the CPI has received about the fires through last week show that out of 30 reported fires, only 10 were investigated by the police. So we don’t know how many of the fires were criminal, or who set fire to the favelas,” she said.

The journalist is conducting research on the fires in São Paulo. Data from her study, along with the work of programmers, journalists, and designers, has been used to create “Fire in the Shack,” a collaborative platform that coordinates information on the fires with data about the value of real estate in the neighborhoods.

In Rio: Past fires, present removals

Suspicious fires are nothing new in Brazil; they’ve been happening for decades. In Rio de Janeiro in 1969, the Praia do Pinto favela (located in Leblon in Rio’s wealthy South Zone) burned down after residents resisted relocation. Now the dubious fires are happening in São Paulo.

Mario Sergio Brum, who holds a PhD in History from UFF (Fluminense Federal University), is on post-doctoral assignment at IPPUR/UFRJ (Federal University of Rio de Janeiro’s Institute for Research and Urban and Regional Planning). [Brum’s book will be launched next Tuesday, October 30th.] He analyzes the historical forces behind the current housing politics in Rio de Janeiro: “Removals never stopped completely, although they lost some strength during the period when democracy was being restored.”

Brum notes some of the reasons removals lost momentum for a time: the renewed political force of the community movement; the power of favela residents’ votes; and the failure of the removal program itself, as carried out by federal and state governments between 1968 and 1973.

Since the reasons the favelas were created didn’t go away, the removals program did not stop the formation of new favelas, nor did it stop the growth of existing ones. Furthermore, the lives of people relocated to low-income housing projects deteriorated to such an extent that most of those projects are now considered favelas.

Another explanation for the temporary decrease in removals, according to Brum, was the opening of new areas for real estate expansion, such as Barra de Tijuca. It became more viable to build new developments in that area than to remove favelas from the center of the city. And so removals continued in Barra in the 1980s, including at the Via Park favela behind the Barra Shopping mall, and at Vila Marapendi, near Barra’s “Downtown” shopping mall.

During Holy Week of 2004, after intense fighting between drug traffickers in the Rocinha community, the subject of removals returned to the public debate with renewed force, as part of the discussion about urban violence. Editorials in the newspapers O Globo and Jornal do Brasil called for taking another look at the location of some of the favelas.

“With the big events coming to town, starting with the 2007 Pan American Games, and the corresponding revival of the real estate market, we have a scenario in which real estate interests, and those concerned with public safety – a justification for some in the society – can join together and reopen the subject of removals, supposedly in the name of a greater good that will benefit the entire city,” explains Brum.

After the rains and flooding of 2010, the subject, which had barely been brought up during other storms, reemerged and was highlighted in editorials and opinion pieces. However, according to the City’s current plans, almost half of the families to be removed are in the area of Vargens, on flat land that was not damaged by the rains.

Things have changed now that we are past the era of dictatorship. Residents are no longer actors who must remain silent. Now there are mobilizations against removals, as we’ve seen in Rio in the communities of Vila Autódromo and Horto. Residents can organize and connect with other sectors of society, which was not possible between 1968 and 1973. This may truly make a difference.