The favelas that make up Maré, in Rio de Janeiro’s North Zone, are home to 140,000 inhabitants and many stories to tell. The favelas’ origins date back to the foundation of Morro do Timbau in the 1940s, but each part of Maré has its own history of emergence.

Nova Holanda, for example, started in the 1960s as a Provisional Housing Center created by the government and coordinated by the Leão XIII Foundation to house the population removed from other favelas in the city, such as Favela do Esqueleto, Praia do Pinto, Morro da Formiga and Morro do Querosene. For many of those families, what was meant to be provisional became permanent, and remains so to this day.

According to Tereza Onã, from Maré’s Memory and Identity Nucleus (NUMIM) of the NGO Redes da Maré (Maré Development Networks), another striking feature of Nova Holanda is that it is constituted by a majority black population. Aware of this, Onã formed a team of female black researchers to investigate Maré’s local memory as tied to issues of gender and race. The meetings between the researchers and long-term residents of Nova Holanda became known as “Tea with the Grandmothers.”

“Nova Holanda has a history that the rest of the city needs to know about; it is the community with the largest number of black residents in Maré. It’s no coincidence that in Nova Holanda we have such a tense relationship with the police,” says Onã, who has coordinated this oral history work for the past four years.

The documentary As Griots da Maré, directed by Diego Jesus and Tereza Onã in 2016, is one of Tea with the Grandmothers’ first outputs. The 15-minute film, which contains the narratives of female Maré residents, is available on the Olhares da Maré Film School’s (ECOM) channel.

“They still don’t have a clear idea about what a griot is,” observes Onã. “I call them griots, but they do not see themselves as such yet. This griot thing has to do with history, with the memory of our blackness. My dream is for them to look in the mirror and say, ‘Wow! I’m a griot!’ This is still under construction. [This work] is a way of giving visibility to them. I’m only here because they’ve been here before me. For us, black people, our ancestry is fundamental. We are in 2019 and the history of the Negro in Brazil still hasn’t been told.” Based on Law 11.645/08, the research team has been discussing memory and identity in Maré. In traditional African culture, griots are the guardians and storytellers of their communities.

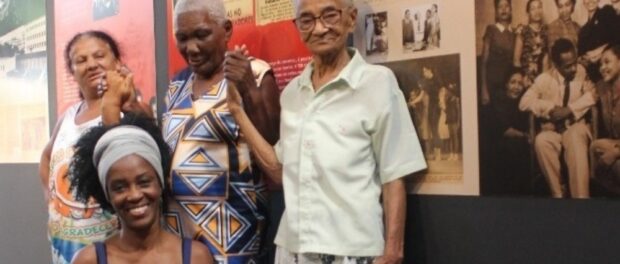

On May 30, gathered at Tea with the Grandmothers during the “Abdias Nascimento, the Art of a Warrior” exhibition, held at the Maré Arts Center until June 15, the grandmothers Tereza (52), Durvalina (88), Eva Iara (59) and Maria Augusta/Aidê (95) shared their experiences.

Dona Durvalina, who features in The Griots of Maré, tells us that she was born in the neighboring state of Minas Gerais and has a large extended family in Maré: “I have five children, 16 grandchildren, 32 great-grandchildren, and six great-great-grandchildren. If I have a birthday party, just my family will be enough to fill the party,” she says, laughing. From the group of grandmothers, Dona Durvalina says she already knew Aidê: Maré “was a community where everyone talked. This is no longer possible today, but I know all my old ones.”

Maria Augusta, known by all as Aidê, is also a native of Minas Gerais state but arrived in Maré when she was 12-years old after the removal of her family from the Morro do Querosene favela. She remembers a fire that took over her house many years ago: “My dear, the house caught fire. It was really sad. I was sleeping when I heard a tchiii-tchiii sound. Then they knocked on the door: ‘Aidê! Aidê! The house is on fire!’ Girl, when I saw that, I went crazy. But thank God, it was all repaired and everything is back in its place,” recalls Dona Aidê, who started going to the Grandmas’ Tea at the invitation of her daughters. “I wouldn’t leave the house. I would only leave to go to the doctor’s and to my daughters’ house. They told me to come and I liked it.”

Eva Iara, who migrated to Maré from São João de Meriti, on the outskirts of Rio proper, shares that she has a twin brother named Adão. That morning was her first Tea with the Grandmothers: “Today is my first time and I enjoyed it. Every time she [Onã] would come by, she would invite me, but I was too shy. Then she said, ‘Leave this shyness and come.’ I liked it, I’ll come more often from now on.”

Onã, who is also a grandmother, states that “there is a history of Maré that only they know.” The meetings also carry out joint actions with the Lima Barreto Popular Library at Redes da Maré, and the Muda Maré environmental education project, including visits to the nearby Piscinão de Ramos pool and workshops: “We need to know Maré better. Those who live in Piscinão say that that they do not live in Maré. This group intends to reduce that distance.”

Besides the group of Nova Holanda residents, Tea with the Grandmothers has another nucleus in Vila do Pinheiro, also in Maré. All in all, there are 12 long-term female residents participating in the meetings: “It is not yet a project. We do not have funding, in fact, but we cannot stop the meetings,” says Onã.

The next step is to collect stories about Maré’s healers, or rezadeiras. “Tea with the Grandmothers is an embryo of this. We will create a project about the healers starting from their stories, and another about the folia de reis festivities in Maré from their stories,” says Onã. With their still unknown stories, the healers mark the narratives of several of Rio’s favelas. They are stories that come from the city’s South Zone favelas as well, from old-timers like Nega Vilma in Santa Marta, Dona Binha in Pavão-Pavãozinho and Cantagalo, Dona Alzira in Vidigal, and Dona Orosina Vieira in Morro do Timbau (Maré).

In the context of ongoing persecution of Afro-Brazilian religions and practices within and outside favelas, it is even more urgent to record these narratives and bring visibility to its leading characters. Dona Durvalina was a rezadeira until she was 70: “I started when I was seven and I stopped at 70. I thought the time had come. God gave everything a deadline, one for when to be born, to walk, to grow, and that was my deadline. Everything has its time.”

Miriane Peregrino is a researcher, community journalist, and teacher with a Master’s Degree in literature from the State University of Rio de Janeiro (UERJ). In 2013, she created the Literatura Comunica! (“Literature Speaks!”) literacy project, which is active in schools, community libraries, and cultural centers. Born in the interior of Rio state, she has worked in Maré since 2013.