Last Monday night in Curicica, Jacarepaguá, in Rio’s West Zone, Carlos Brandão held up three blue circles cut from construction paper. “City government,” he announced to the thirty people seated encircling him on a restaurant patio.

One woman said tentatively, “Medium?”

“No, big, big!” chimed in several others.

“Let’s talk about it,” said Brandão. “You all indeed pay part of the budget for the city government.” Although they did not discuss the specifics, Curicica favela residents pay various combinations of income and property tax – so they agreed with Brandão and moved to the topic of how beholden the city government was to providing improvements to the community. Eventually they decided the city had a large obligation, and so Brandão wrote “Prefeitura” (City Hall) on a large blue circle in permanent marker and pasted it onto a paper chart he was creating on the wall.

Brandão works for ISER, a non-governmental human rights organization, but he was brought in to lead the meeting by the city’s Morar Carioca infrastructure upgrading program. Since its launch in 2010, Morar Carioca has pledged to introduce a more participatory element to construction projects that have been arriving in Rio’s favelas for the past sixty years. It’s still the beginning of the process here in Curicica. Construction is not scheduled to start for a few months; this is the third public meeting thus far.

This meeting did not delve into the specific. Residents who came wondering if their particular street would get lighting installed left without an answer. Instead, the group engaged in a more theoretical discussion about their roles in the upcoming process. Their roles would be important, Brandão emphasized. He began the evening having everyone go around in a circle, saying their name, their community, how many years they had lived there, and their occupation. People had come from Asa Branca, Vila Calmete, Abandiana, and Village Campos de Paz (known to the government as Vila União). They were bakers, truck drivers, business administrators, and one president and one vice-president of community Residents’ Associations. The longest period of residency in the area was 33 years; the shortest, eleven.

Brandão asked about the original founding of the communities, and residents described the establishment of the first favela in Curicica in the early 1980s by workers on construction sites in the early days of Barra da Tijuca. The process of real estate development still heavily characterizes the area, where dusty new roads separate swamps from condominiums and the occasional monumental sporting arena.

In 2009, Asa Branca Resident Association President Carlos Alberto “Bezerra” Costa wrote a letter to the Prefeitura requesting public works in Curicica. Three years later we sat in open discussion about the influence of the upcoming World Cup and Olympics on the upgrades—it would not be happening, everyone agreed, were the communities not very near the site of the future Olympic Village. “That doesn’t mean we should reject the construction,” said one resident. Far from it, the group considered the approach of the construction a starting point for the evening of suggestions.

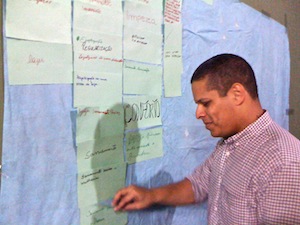

After the introductions, Brandão passed out green slips of paper and pens to everyone present. “Think of your ideal community, as you would imagine it in your dreams,” he said. “What is one word that describes it?” Everyone wrote silently and then handed the slips of paper to a uniformed Morar Carioca attendant. Brandão had taped a large sheet of paper to the restaurant exterior that made a wall behind him. He pasted people’s adjectives in columns on the left, reading them aloud: “Leisure…Comfort…Clean….Regularization…Education….Culture.” The group agreed that one of the best things about Curicica’s communities was their strong sense of community.

Next, Brandão repeated the exercise having people write down a few challenges the communities faced and circling the one they deemed most important. He pasted them up on the right. More than half listed better sanitation as the most important thing to be addressed; others listed security and accessibility. Then, in the middle, Brandão had participants choose the size of blue circle that corresponded to the degree of responsibility various groups—such as the national, state, and local governments, the Residents’ Associations, and the residents themselves—had for addressing these issues.

The discussion this prompted was a long one. When comments died down, Brandão suggested the group consider the role of a few actors they didn’t think of immediately. One was the justice system—Brandão encouraged residents to know their rights throughout this process, and Bezerra followed up telling residents to personally track projects near their homes. Another was fee-for-service utility companies such as Light for electricity and CEDAE for water and sewerage. Occasionally the thoughtful tone gave way to jokes, with the Asa Branca section of the circle being told to calm down more than once, and later on, a few people speculating about what they were missing on that night’s episode of Avenida Brasil. Talk became most serious when several residents said their greatest fear was that people would face removal as was happening in nearby Vila Autódromo. Indeed, a portion of the Bus Rapid Transit line TransOlímpica is currently set to run through Vila União, a Curicica favela.

Brandão did not know whether such removals would occur, but encouraged residents that their opinions would be heard if they kept participating in the planning process. Morar Carioca staffers assured the group they would inform community leaders of the next forum. The staffers did not collect any formal recommendations based on the evening’s discussion—diagnostic drawings for the project were already announced by the architecture firm in a previous, private meeting—but their message was one of general availability to residents. Brandão reminded the group that it was important both to continue debating these issues and to remain pragmatic. “You have to work with the relationships and the resources that you have. You can’t put makeup on them,” he said.

Facilitation meetings like this, of course, are easy to carry out when topics remain abstract. This is the first early-stage participatory meeting Brandão has directed; he said the others in Cajú and São João went smoothly. He foresees a bumpier ride in communities where he will arrive at a later phase in the upgrading process—he will be doing dispute resolution, for example, in Providência, where there has been robust community protest of government actions.

In Curicica, Monday night’s meeting ended with the choice of a large blue circle to represent every actor in the upgrading process. The Prefeitura, the state, the Residents’ Association—meeting attendees thought they all have significant responsibility for how things will proceed. So too, they agreed, with Morar Carioca staffers nodding along, did the residents themselves.