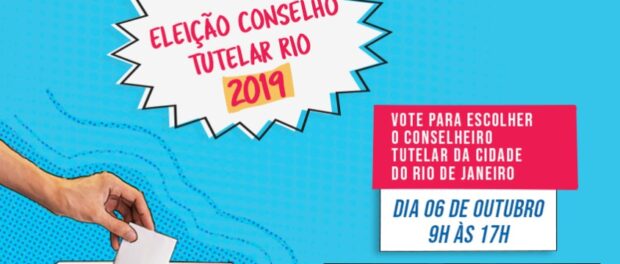

Elections for Brazil’s Guardianship Councilors (Conselheiros Tutelares, locally-elected agents of Brazil’s Conselho Tutelar, or Child Protective Services) for the 2020-2023 term will be held on October 6, 2019. In Rio de Janeiro, 95 councilors and 95 representatives will be elected and distributed across 19 Guardianship Councils. These are autonomous entities geared towards ensuring the rights of children and adolescents, created by Brazil’s Child and Adolescent Statute (ECA). Councilors act as spokespersons for their respective communities in dealings with government agencies and other entities to ensure these rights are respected.

Guardianship Councils are responsible for meeting with and providing counseling to parents or caretakers; requesting public services related to health, education, social services, welfare, employment, and safety; reporting infractions of the rights of children or adolescents to the Public Defender’s Office; and assisting the local Executive Branch in preparing budget proposals for plans and programs related to the rights of children and adolescents, among other duties. The ECA also establishes that it is “the duty of the family, the community, broader society, and the government to safeguard, with absolute priority, the rights related to life, health, food, education, sports, leisure, professionalization, culture, dignity, respect, freedom, and family/community living” of children and adolescents.

Prior to the elections, candidates undergo an objective examination on information specific to the ECA as well as a written test concerning the professional duties of a guardianship councilor. This examination ensures that those elected indeed have the knowledge required for the position and that they are aligned with its objectives. Once elected, they also undergo a training course and only then are instated. Currently, the candidates are campaigning, holding meetings and discussions so as to allow voters to get to know them, including their personal and social backgrounds and their commitment to promoting and defending the rights of children and adolescents.

Voting for guardianship councilors is optional and open to all registered voters. Individuals will choose between candidates running for the Guardianship Council in their voter registration zone.

To check which of the 19 Guardianship Councils is affiliated with your voter registration zone, the respective candidates, and voting locations, click here.

The Role of the Guardianship Councils in the Favelas

In the favelas, where the State only tenuously guarantees citizens’ rights, the importance of the Guardianship Councils becomes more pressing. This is exemplified by a case in February 2018, where children were searched during a police operation in Kelson’s, a favela in the North Zone of the city, an act guardianship councilors subsequently declared unconstitutional.

In the favelas, where the State only tenuously guarantees citizens’ rights, the importance of the Guardianship Councils becomes more pressing. This is exemplified by a case in February 2018, where children were searched during a police operation in Kelson’s, a favela in the North Zone of the city, an act guardianship councilors subsequently declared unconstitutional.

“Being a guardianship councilor in a region with a favela is not the same as in other areas. There is a different set of demands and needs. The social construction of an individual takes place differently,” said one candidate, highlighting the issue of children missing classes due to police operations, a challenge unique to the favelas. He also emphasized the role of guardianship councilors in requesting public services for an area and influencing budgetary allotments for various programs. “There are many ways in which the State is absent or violates citizens’ rights, in relation to food, sanitation, energy services, internet services. This, for example, directly influences the schools’ ability to provide services,” he concludes.

A councilor’s prior involvement and familiarity with an area ensures they will be able to integrate better with residents and earn their trust. This enhances their ability to get involved and allows their contributions to more precisely target the programs and services most needed to confront the violations of rights and meet the needs in each area.

Guardianship councilors have an ambiguous reputation with citizens, since, while they play a key role in providing oversight to prevent child labor, parental abuse, and other violations of the rights of children and adolescents, a number of councilors cling to a distorted, punitive take on what the “principle of the best interest of the child and the adolescent” might be, established in the Federal Constitution and the ECA. Many, because of this mindset, resort to separating children from their families and sending them to institutions, even though the ECA recommends this be the exception, not the rule. In other words, it would only be acceptable “after all possibilities for keeping the child or the adolescent with their natural family have been exhausted.”

“Calling the Guardianship Council” has become a threat amongst many families whose own rights are already fragile, a threat seen as synonymous with sending a child to a shelter or putting them up for adoption. “The Councils are still seen in the favela as a punitive, police-like force. People think the councilor is someone who will take the child away. This is a reflection of the misunderstanding of the councilor’s role. We need people who are committed to human rights, especially in the current scenario,” said another candidate.

In this regard, mothers who are homeless on the streets with their children, who leave their children alone at home to be able to work, or who make their children work, are examples of cases where the State prefers to separate the children from their mothers and send them to shelters instead of mitigating the vulnerability affecting the family with social policies (such as social rent, access to daycare, and access to Bolsa Família, a federal family cash transfer program), such that they would have better conditions for raising their children. If the parents or the family want to take care of the child, the State should create conditions for them to do so instead of transferring the child into a system that burdens the State with additional responsibilities, not to mention the psychological effects it has on the children.

“The challenge is to demystify the real power and the real role of the guardianship councilor. This role is that of defending the rights of the children but also of the families. The councilors do not have the power to separate children from their families. They do not have the power to enforce judicial measures. They have the role of being responsible for them, of representing the community, of requesting services, of working with residents to demand what the favela needs,” said a third candidate.

Electing candidates from favelas is also important “so that young people see that they themselves could one day be in that role,” said one of the candidates mentioned earlier. “It’s a position for which only a high-school level education is required, but most of those elected have college degrees. This is a reflection of the lack of opportunity for local leadership, who don’t have access to higher education, who are unable to adequately prepare for the examination, who aren’t aware of the documentation required, who aren’t aware that they can request exemption from the matriculation. They need to understand the importance of voting and of democratizing this process,” she adds.

A Wave of Conservatism in the Guardianship Councils

Employees (who asked not to be identified) shared widely circulated messages that are representative of the current thinking of the Guardianship Councils and of some of the candidates. They sent out the following message on social networks:

“There are some who want to join the Council in order to fight gender ideology… There are some who say that the problem with children and adolescents in Brazil is that God is missing from their lives, and that only prayer can fix this.”

These employees are concerned that disrespect for religious freedoms and a restrictive definition of a family and of moral codes is seeping into the Councils, especially given the rising conservatism that Brazil is currently seeing. This bias goes against the secular nature of the State and its agencies, which, according to the Constitution, must not become a vehicle for any specific form of morality or religion. This concern is even more relevant given the mobilizing potential that conservative candidates have with churchgoers, given that voting for these Councils is not mandatory and that most of the population does not mobilize to participate in the Guardianship Council vote.

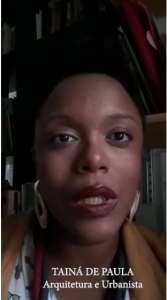

This concern also became evident when four guardianship councilors from the Jacarepaguá region were removed from office in the first semester of this year. Architect Tainá de Paula, raised in the Jacarepaguá favela of Loteamento as well as the Rio de Janeiro Association of Guardianship Councils (ACTERJ), denounced the process headed by the Ethics Committee of the Guardianship Councils, which resulted in their removal from office being classified as arbitrary and biased. However, the Rio de Janeiro Center for the Defense of the Rights of Children and Adolescents (CEDECA) said that the Ethics Committee overstepped the boundaries defined by law, and questioned the legality of the decision, which was not accepted by the Internal Affairs Department of the Guardianship Councils, nor was it approved by the Rio de Janeiro Municipal Council of the Rights of Children and Adolescents (CMDCA). Several candidates mentioned political persecution.

This concern also became evident when four guardianship councilors from the Jacarepaguá region were removed from office in the first semester of this year. Architect Tainá de Paula, raised in the Jacarepaguá favela of Loteamento as well as the Rio de Janeiro Association of Guardianship Councils (ACTERJ), denounced the process headed by the Ethics Committee of the Guardianship Councils, which resulted in their removal from office being classified as arbitrary and biased. However, the Rio de Janeiro Center for the Defense of the Rights of Children and Adolescents (CEDECA) said that the Ethics Committee overstepped the boundaries defined by law, and questioned the legality of the decision, which was not accepted by the Internal Affairs Department of the Guardianship Councils, nor was it approved by the Rio de Janeiro Municipal Council of the Rights of Children and Adolescents (CMDCA). Several candidates mentioned political persecution.

On June 6, 2019, during an ordinary session of the Chamber, City Councilor Reimont of the Worker’s Party also reported that their removal from office comes at a time of greater political setbacks, given that these councilors were more progressive and were pushing for their councils to work more democratically, privileging collective decisions over decisions that were centralized in the hands of individual councilors. In his view, they were removed from office unilaterally and with no right to redress. This contravenes the law governing the Councils, which lists removal from office as the last of three possible measures that can be taken.

Another concern shared by a number of employees and candidates concerns Bolsonaro’s decree for reduced gun control, which grants the guardianship councilors the right to not have to prove a “pressing need” to bear arms in public, which only underscores the perception that the role is punitive.