For the original article in Portuguese published by the Institute of Alternative Policies for the Southern Cone (PACS) on Medium, click here. Reporting by Gizele Martins and Jessica Santos in partnership with the Brazilian Fund for Human Rights. This is the third article in a five-part series.

The position held by Brazilian authorities [of “acts of resistance killings,” or police killings of civilians claimed to take place in self defense] sends a message of guaranteed impunity for police that kill. Rio de Janeiro’s violent death rate—which includes deaths due to police intervention—is up to nine times higher among black children and adolescents.

The far-right came to power in 2019, and the first months of the year already showed that this year, and likely the next few, will not be easy for those who live and survive in Brazilian favelas and peripheries. Let’s remember: Jair Bolsonaro won the presidential election with his “finger guns,” and, in Rio de Janeiro, current governor Wilson Witzel, even before being elected, had already assumed openly racist, pro-militarization, and elitist positions. It is no coincidence that, between January and April alone, Rio had the highest number of cases of auto de resistência (acts of resistance: a Brazilian legal designation for an event in which someone is killed in confrontation with the police, indicating the police acted in self-defense) in the last 20 years: more than 400.

One semester was enough to dispel any shadow of doubt between the obvious association of gestures, speeches, and practices of these authorities and the deepening of the black genocide, the militarization of daily life, and, consequently, the strengthening of a police force that kills at will (though only in certain areas).

Children and teens from the favelas, like those in any part of any Brazilian city, should have a right to their childhood: to study, to play in the street, to buy candy, to play soccer, and to fly kites. Yet, judging by the deliberate permission of the irresponsible use of force in these territories or by the government’s historic passivity in the face of violence against these young citizens in formation, past and current politicians must believe that black children and teens living in peripheries can be killed. As though their dreams and those of their families did not die along with them.

Data from the 2018 Child and Adolescent Dossier of the Institute for Public Security (ISP), indicate that in 2017, 635 children and teens were murdered in the state of Rio. The data were calculated by cross-referencing Civil Police and health institution records. The context is particularly pronounced among adolescents: more than one quarter (28.6%) of these deaths are homicides resulting from police intervention. Between 2007 and 2017, the murder rate in this age group increased by 68%.

Also according to the dossier, violent deaths (involving homicide, homicide as a result of police intervention, personal injury followed by death, and robbery followed by death) mainly affects Afro-Brazilians. In Rio de Janeiro, the rate of “black children and teens is 45.3 victims per 100,000 black residents from 0 to 17 years old, almost nine times higher than the rate among white children and teens, 5.1 victims,” shows the document. “Concerning the victims’ profiles, they are predominantly male (…) 95% (167 victims) of homicides resulting from police intervention and 89% (403 victims) of homicide victims were male,” the dossier reveals.

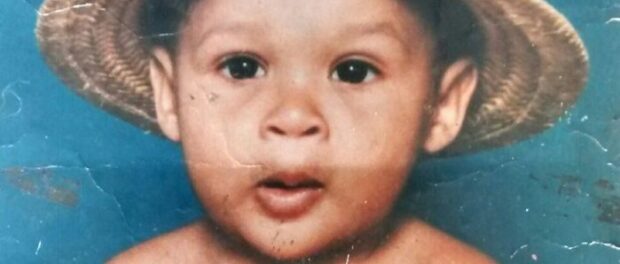

One of the cases that gained international attention was that of the boy Maicon, which occurred over 20 years ago in Rio. Maicon was two years old when he was murdered by police in the Acari favela, in the city’s North Zone. Jose Luiz Farias da Silva, Maicon’s father, has been denouncing the death of his son for 23 years, seeking answers to the crime. “The case got registered as an auto de resistência. I became an activist after that. April 15 marked 23 years [since my son was killed], an absurd case not only for Rio but for the whole country: a child became known as a criminal at the age of two. Brazil violated my right to answers about the case. More than that, they violated the right to life of my son,” says Silva. What is most surprising is that Maicon’s case expired and was archived, showing an incapability or lack of commitment to the investigations.

Natália Damazio, who worked as a lawyer and researcher for the Rio-based NGO Global Justice, began working on litigation through the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights from 2014 to 2015. “In relation to the murder of Maicon, there was a shootout happening in Acari. That’s why it was filed as an auto de resistência. It was archived due to lack of evidence. Once a case is archived, only the presence of new evidence can re-open it,” she explains.

The lawyer affirms that, after much difficulty, on the day of the case’s expiration, a meeting took place with the Rio de Janeiro Public Prosecutor’s Office. According to Damazio, the Public Prosecutor’s office was more interested in archiving the case than answering the question of what could be done. Now, the case is only monitored internationally.

“We are talking about a 20-year-long case. It should never have lasted 20 years. There were clear testimonials. One of the officers even confessed that he fired a shot, but it wasn’t carried forward. It’s scary because there was a decree at the time [under then-Governor Marcello Alencar] called gratificação faroeste (the Wild West Bonus). In this case, they [the police] received a financial reward for ‘success in this operation,’” added Damazio.

Authorities Send a Message of Guaranteed Impunity

Like Maicon’s, countless other Brazilian children and adolescents suffer violent deaths daily. “There are several cases of children, babies murdered by the police and it’s very serious. Can you imagine what would happen in this country, in this state, if the Rio de Janeiro Military Police killed a ten-year-old boy leaving school in Leblon [a wealthy neighborhood in Rio]? The city would stop, the country would stop, the Security Secretary would lose his job, the governor would follow, even the president. But no. Since they are black children in the favelas, you get this whole imaginary that part of the society carries with them, deeming them ‘seeds of evil’ or something similar,” affirms Lucas Pedretti, a historian who researches State violence in Brazil’s dictatorship and democracy.

For Pedretti, it’s as if it doesn’t matter what the person did. The fact of being a black person, of living in a favela, is enough to not only cause mistrust, but for people to call the person a criminal. “When this happens with a child, it is even more serious. It’s the idea that because the child is black, because he lives in the favela, that the child will become a criminal. So this execution, this murder, is seen as natural by a significant part of society, which allows this to keep happening. The fact is that no one deserves such treatment,” adds Pedretti.

A number of issues keep cases like Maicon’s from being investigated, among them police corporatism and the criminalization of poverty. Such factors transform homicides into “collateral damage” or “stray bullets.” “We have a serious problem in terms of forensics. It’s done by the Civil Police, without exception. We need independent forensics. The second point is that when an event is registered as an auto de resistência, in the moment of the denunciation, the analysis accepts that the event occurred as such. But it is not punishable, because there is the idea that the person (the police officer) was not to blame. This occurs because cases such as these take place in the favelas. Who fired the shot isn’t investigated; the victim is investigated” observes Damazio.

There is also a lack of investigation for auto de resistência cases. Historian Lucas Pedretti remembers that without judgment from case to case, everyone ends up blameless, resulting in de facto permission to kill. “There exists a legitimization from public authorities as well, because of the lack of interest in investigations. This increase in auto de resistência cases is serious. Unfortunately, we can’t say we’re surprised. This is to be expected when you have a governor that says [the police] will ‘aim at their little heads,’” he criticizes.

In this way this genocide is a process organized by the official powers themselves: the governments verbalize and give orders, and the police acts without investigating. These are mechanisms, instruments—including legal instruments—that permit the reproduction of this model and guarantee impunity for the police officer who kills, who executes.

In 2017, during the government of former president Michel Temer, the judgment of murders committed by the military against civilians was transferred back from civil to military courts. If the number of cases that were effectively investigated, judged, and sentenced in the civil courts was already low, this transfer may have provided an even greater stimulus for impunity. In this way, the entire system works to show to the police officer in the field that he can execute and will have the guarantee of not being held responsible for this act.

This is the third article in a five-part series.