For the original article in Portuguese by Carla Regina published in Agência de Notícias das Favelas (ANF) click here. For its republication in Agência Pública, click here.

This article received the 2019 ANF award for best favela-based article in the Culture category.

I could start this article introducing myself, speaking a little about me, who I am, about my aspirations and goals. But I’m going to start by presenting my community, Morro do Turano, the place where I was born, where I grew up, and where I continue to live.

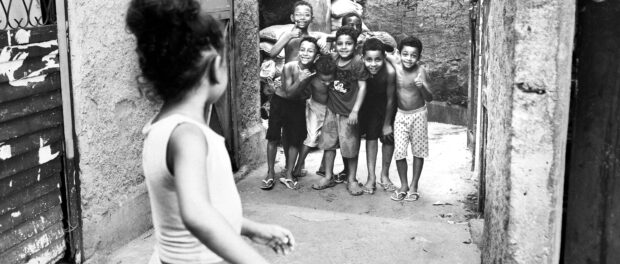

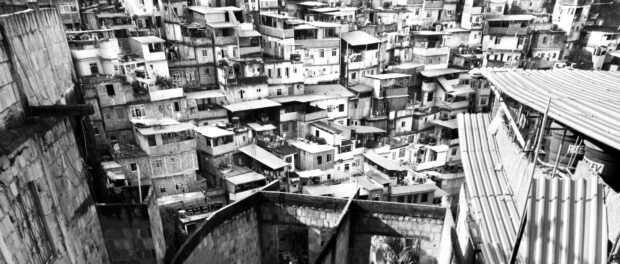

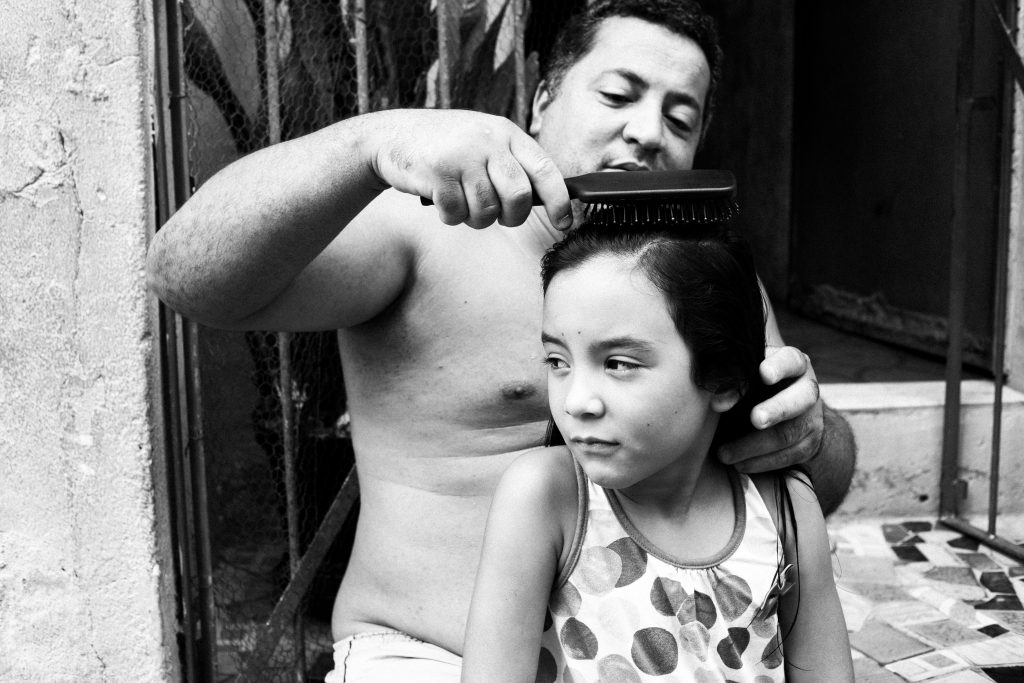

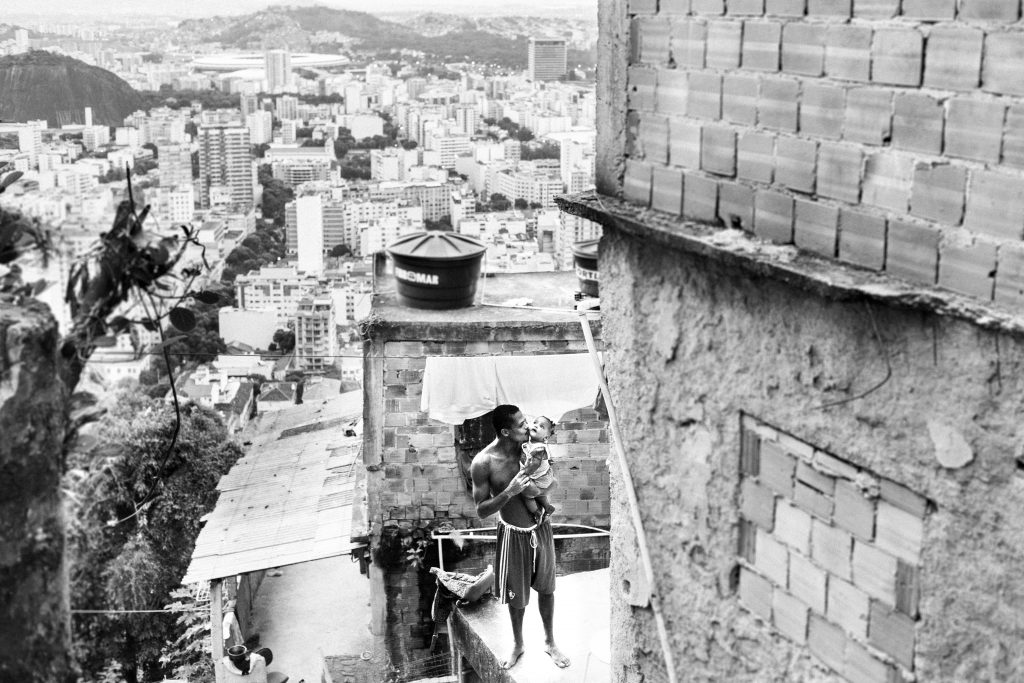

Over the last few years, like many favelas, Complexo do Turano, comprised of seven neighborhoods, home to more than 13,000 residents, gained fame in the media for being violent and dangerous. But we, residents, know the true reality inside our communities, and so, as those born and raised here, can speak accurately about what actually happens (or doesn’t) way up in the hills or down in the alleys. Morro do Turano is a wonderful place, and I’m very proud to say I’m from there.

I will start our tour of the favela at the top of the hill, where it all began.

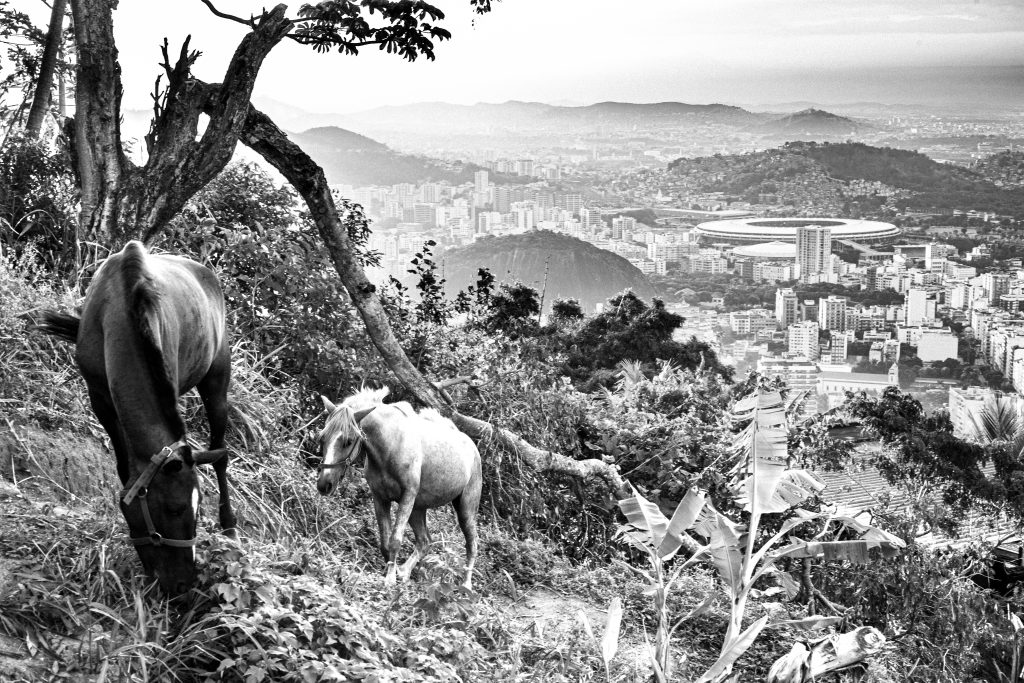

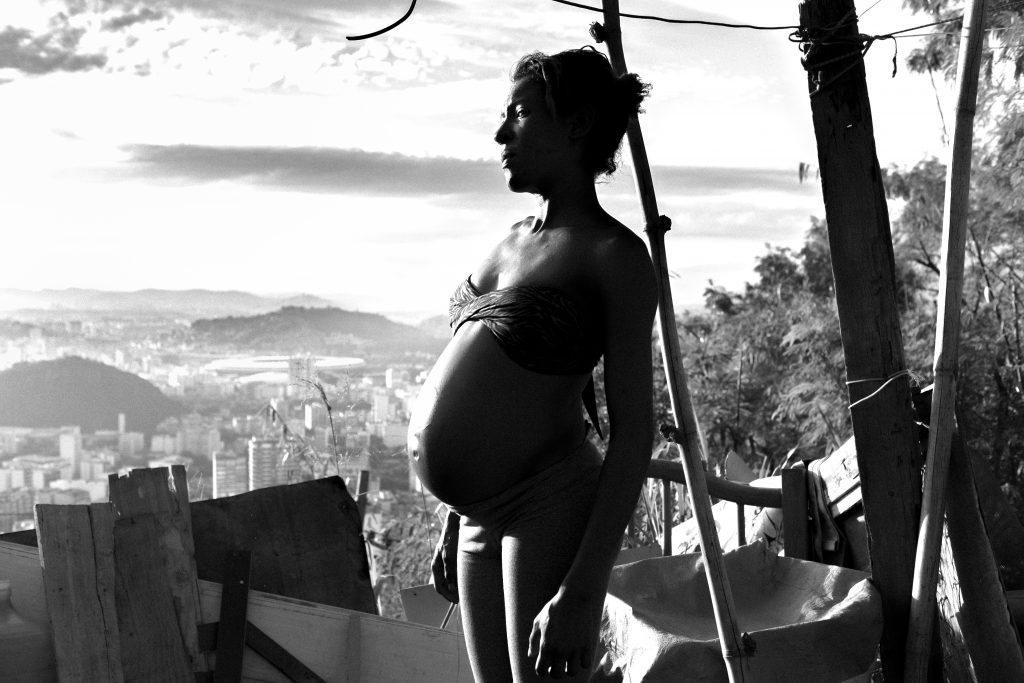

Up top, we have the Pedaçinho do Céu (the Little Piece of the Sky) neighborhood, which gives us a stunning view of the Tijuca area and a good part of the city. A little lower, we have Tanque (Tank), where, in the past, women washed their clothes and their boss’ clothes in collective wash tanks, according to older residents’ stories. Right there we have the Divisa (Division), a path through the forest that separates Morro do Turano and Morro do Salgueiro, with an enchanting view of Tijuca, adjacent areas, and even parts of the suburban cities of Duque de Caxias and Niterói—without forgetting, of course, the beautiful view that we have of Maracanã stadium, a Carioca treasure.

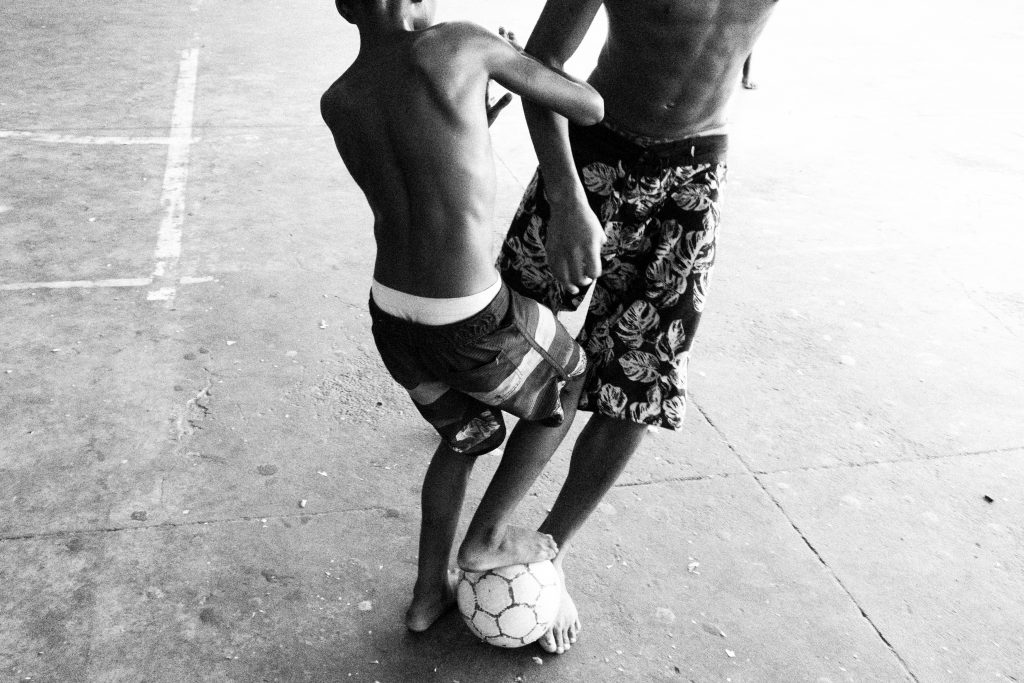

Descending a bit more, we have Raia. According to some of the older residents, this name was given back when the favela was first founded, when the area was part of the Turano plantation, and the first name given to the area was Fazendinha (Little Plantation). Because of the large Arraiá gathering that the residents held there during the June festivals period, the area eventually became known as Arraiá, and, as is custom among Cariocas, abbreviated to Raia. Here, there are subdivisions like Fazendinha, Miolo, Entradinha da Chacrinha, Caminho da Caixa d’Água, and the famous Quadra da Vista Alegre, or Quadra da Raia—a space where children get together to play ball and teenagers and older kids play pickup games. On weekend nights, there is a famous swing dance, very well known in the community, called Raia Swing, where people go to have a good time and dance to the sounds of Bebeto, Jorge Ben Jor, Banda Copa Sete, Elson do Forrogode, etc.

And we are going to descend a little more, because lower down we have an area called Televisão, that got this name for having an expansive view of Matinha and of other parts of the favela that are located in Rio Comprido. Descending just a little more, we arrive at Piauí, where a little shop used to be run by an old resident, who, sadly, has passed away. He rented studio apartments to whomever needed housing, and anyone that stayed there would say that they were “living in Piauí.”

What a stroll, right? And I didn’t even take us to the very top of the hill, because this favela, like I said, is very big, one of the largest in the North Zone, and I am taking us through the part that’s in Tijuca. But we are going to continue down, because now I’m coming to Igrejinha, an area that is still called this by the oldest residents because a really old Evangelical church prays there to this day. Below, we have Beco da Macua, or simply Macua, an area that, for some time, was considered one of the most dynamic parts of the hill because the residents are, shall we say, stubborn, and, when there is any type of injustice committed on the part of the Military Police, they unite and make a lot of noise, even mobilizing residents from other areas.

Leaving Macua, we arrive at Escolinha, home to the Frei Cassiano Municipal School. According to accounts from the elders, the friar himself helped to build and launch the school in the early 1970s—just as he launched the Military Police Station, which was deactivated for a time for the installation of the Pacifying Police Unit (UPP) under the administration of Governor Sérgio Cabral, and was later reactivated. On the side, there is a path that leads to Matinha, or Beco do Posto, which is also part of Escolinha.

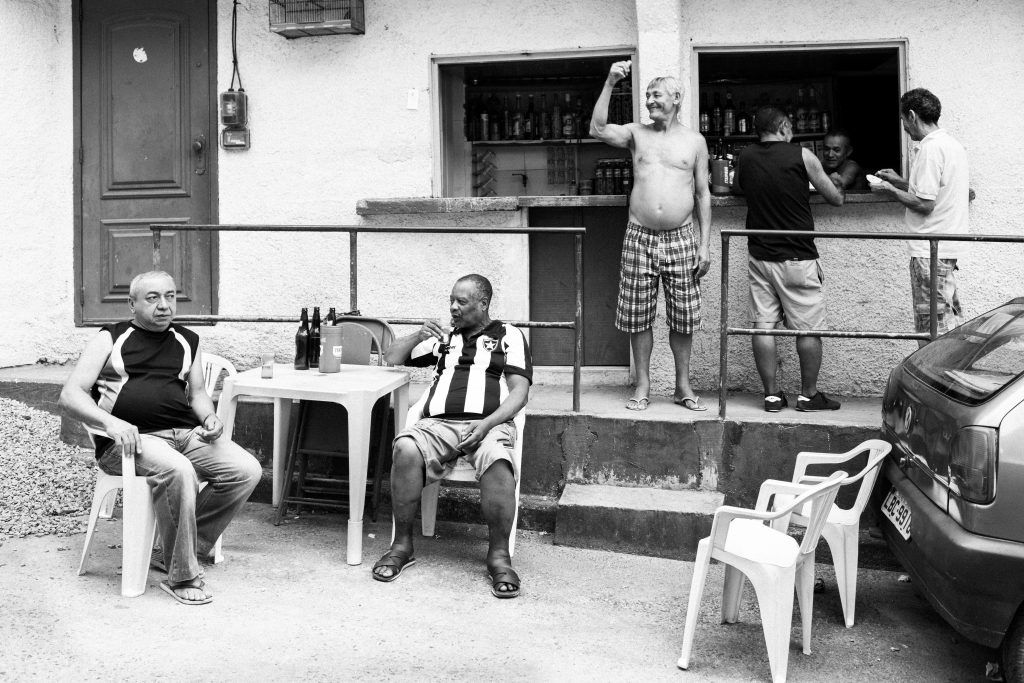

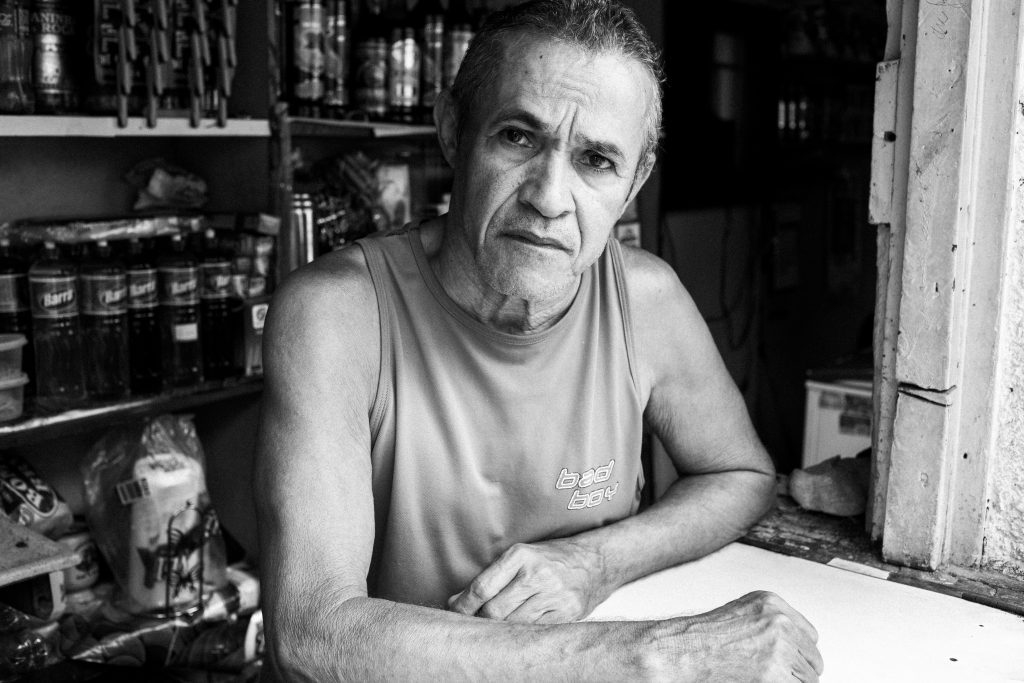

At the base of the school, there runs a path, almost like a hallway, where there’s a commercial strip with little stands, shops, shacks, and a vegetable market. Some of the stands here are very old, like the Stand of Manuel do Cardoso, a bar that belonged to a Portuguese man by the same name. With his death, it ended up being passed down to his son. He also rented out apartments in the alley next to the bar. As a result, the spot ended up being baptized with his name: Cardoso’s Alley. And there is the old Stand of Mr. Joe, which was also passed on to be managed by Joe’s children after he got sick and died. And, finally, the Stand of Pelado, Joe’s son, who inherited a knack for business from his father, but sadly, in April of last year, became ill and ended up leaving us, to the sadness of most of us who were used to his irreverence and joy—using the parlance of the favela, accustomed to his “zoação” (playful mockery).

Now I am arriving at the part of the hill that, modesty aside, is the best, and is where I have loved most since childhood, because it was where I was born, where I grew up, became a mother, and, now, a grandmother.

I have been descending nice and slow and have now arrived at Chapa, whose name was given by a young group of friends in the early 1990s, in homage to another group of young people in the 1960s and 1970s, who would get together in the area and were called the “Turma do Chapa” (Chapa Crew). The group, besides meeting every day, threw parties in the street for the residents, especially on Children’s Day. They wore shirts with the name of their group and the name of each member. They had a sort of brand.

With the fame of the Chapa Gang, the residents, not only of this part, but also of other parts of the hill, began to call that area Chapa Gang and, later, just Chapa. New generations of groups of friends were born and perpetuated the old name. The two old groups don’t get together anymore, but the name they gave to the area ended up being eternalized in the funk lyrics of MC Menor do Chapa, who was also a Chapa resident.

But just because the Chapa Gang doesn’t get together anymore doesn’t mean that the liveliness has stopped, because the weekends continue “bombando” (booming), with lots of forró at Ivanildo’s Bar, with people at the other bars and in the street enjoying funk, drinking that cold beer, children playing, and so on. And, on game days, the guys gather at the doors of the stands to watch soccer. Even with so many problems—and all of us know what they are—we still try to enjoy life.

Chapa is where I was born, played in the street, slid down the slope, known as Estradinha Nova, ran after sweets on Cosme and Damião day, climbed trees on the land of the old and now-gone Santa Dorotéia High School. On days when the water cut out, I faced lines together with other residents to get water from Caixa-d’Água, a wide area with a substation of the state water and sewerage utility (CEDAE). As a child of the favela, I had a childhood and adolescence that was simple, but still really cool. And when my children were born, even in very different times, they were still able to enjoy their childhood, despite innumerable difficulties.

I stopped for a bit in Chapa, but I will continue the Turano tour, descending and passing through Barra Funda until arriving at Escadinha, a staircase that leads to the old block of the long-standing Cometa do Bispo carnival troop, which was founded in 1962 and is still active. Besides hosting the group’s rehearsals, the space is also used for parties and celebrations, dances, etc.

On the other side of the street, there is the Herbert de Souza State High School, which holds classes not only for students from Morro do Turano, but also from other adjacent favelas.

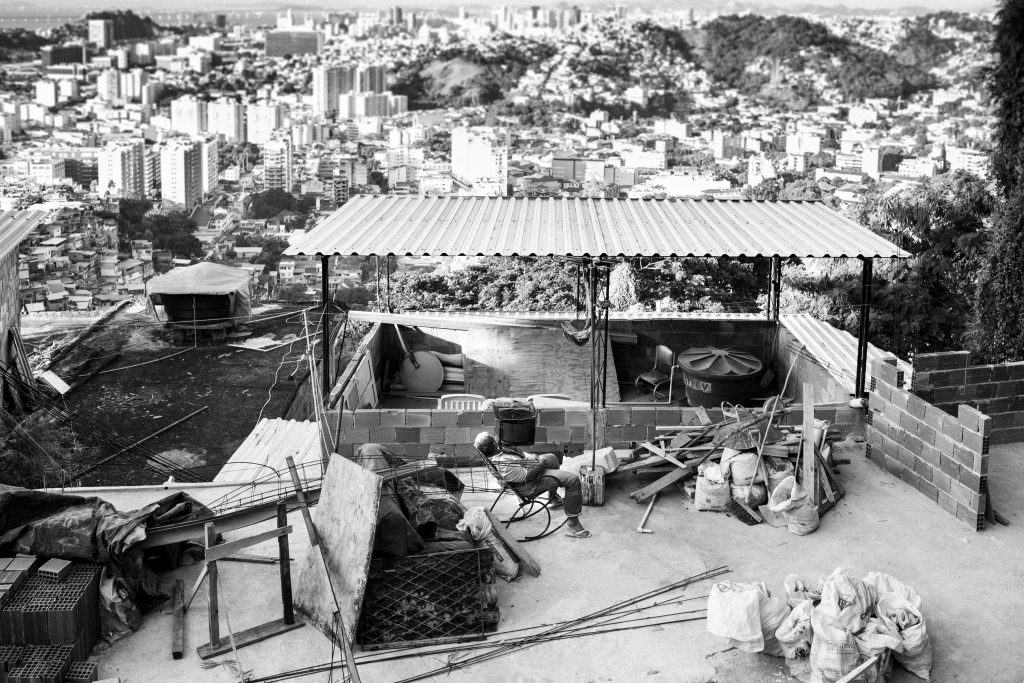

On the weekends, the sports courts are opened up for kids to play freely, even for soccer and martial arts groups. Near the high school, a moto-taxi stop has now started working, and some years ago in that area, after the works of the Favela-Bairro program, a local service-provision area started running, with things like repair shops and barbershops. The number of homes has increased too, all the way up to the entrance of the favela, which we call Curva, where a tire shop operates and, more recently, there came to be a bar and a snack stand, which is located, more precisely, on Barão de Itapagipe Street, or simply “Barão,” as we residents usually call it.

Wow, I’ve made it to the foot of the hill, and now I’ve seen just how much everything has changed from when I was a kid until now, how everything became so different. The Light utility’s wooden energy post isn’t even there anymore; when the energy would go out, we would go and rock it back and forth to get the power back on. Yeah, a lot has changed in the favela and, why not say, for the better, but there is still much to be done in my dear Morro do Turano. Many improvements are still needed for us, the residents, to have a good quality of life.

Well, now that I have presented my beloved favela, my dear Turano Hill, let me introduce myself.

Hello, or using our favela parlance, “aí manas e manos, fala tú, suave?” (“hey brothers and sisters, talk to me, everything good?”). My name is Carla Regina, I am 45 years old, I am the mother of three children, grandmother of four grandchildren and I was raised in Morro do Turano—born February 8, 1973, leaving the maternity clinic directly for Turano, where I have lived to this day. I hope I have been able to “passar a visão” of this interesting and vibrant world to all of you.

All photos by Fabrício Mota.