For the original article in Portuguese published by data_labe on Medium, click here. Reporting by Gabriele Roza, with data analysis by Juliana Marques, and art by Giulia Santos.

Mayor Marcelo Crivella claimed he would benefit 21 favelas with works projects by 2020, all of them having been initiated in previous administrations. A lack of transparency marks both the present management and past favela upgrading programs in Rio de Janeiro.

In July 2017, when Mayor Marcelo Crivella shared his Strategic Plan, civil society organizations met with one another to discuss what was missing in the document. The principal critique was a lack of transparency and insufficient details regarding its goals, forecasted to be finalized between 2017 and 2020. The only goal concerning favelas received a single sentence: “Benefit 21 favelas in Areas of Special Social Interest (AEIS), carrying out upgrading works by 2020.” Given the lack of specificity regarding the goal, such as which works would be carried out, which areas would benefit, and what resources would be invested, it has not been clear, until now, what Crivella’s management was referring to in regard to the finalization of past works.

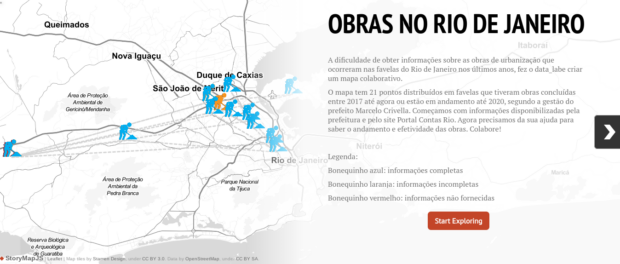

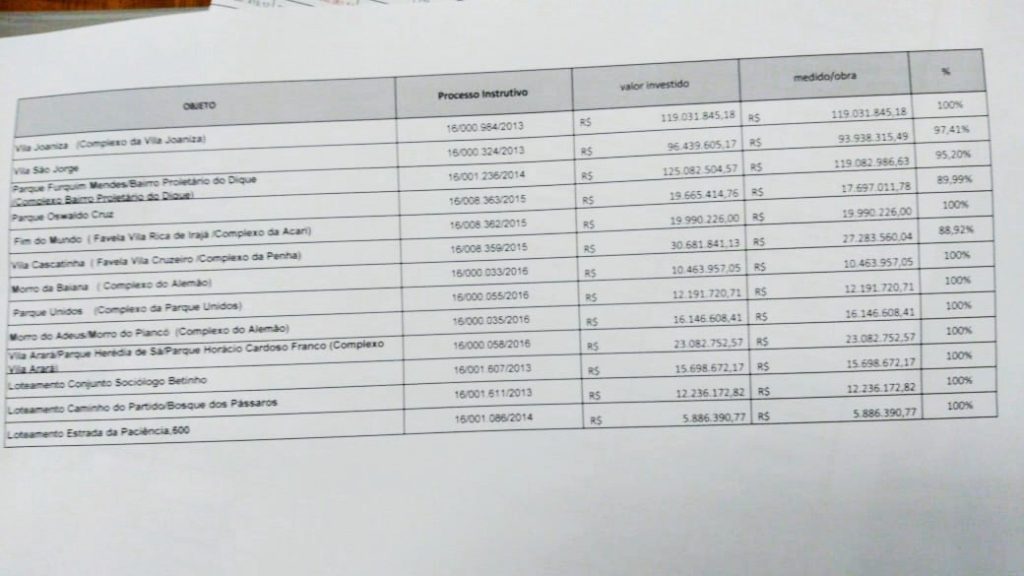

In October, the Municipal Secretariat of Housing, Infrastructure, and Conservation (SMIH) responded to data_labe’s request with a list of the 21 favelas to be benefitted by the current government (see the map below, or here) and an extremely low-resolution photo (see below) with processing numbers, the amount allocated for each project, and the percentage of value invested so far. According to the City, works were completed in 13 favelas (Vila Arará, Parque Herédia de Sá, Parque Horácio Cardoso Franco, Morro da Baiana, Morro do Adeus, Morro do Piancó, Favela Vila Rica de Irajá, Complexo de Acari, Complexo do Parque Unidos, Complexo da Vila Joaniza, Loteamento Sociólogo Betinho, Loteamento Caminho do Partido, and Loteamento Paciência 600), and six others have works that are in their final phase (Parque Furquim Mendes, Proletário do Dique, Favela Vila Cruzeiro, Complexo da Penha, Parque Oswaldo Cruz, and Vila São Jorge). The SMIH did not send information regarding works in Barreira do Vasco and the Vila do Mexicano.

The SMIH’s press team stated that these are works that are part of the Favela-Bairro program which have been concluded or are in the final stages and that, “in the last three years, Favela-Bairro has implemented 154,476,000.41 meters of new water, sewerage, and drainage networks; 225,254,000.16 m2 of roads; 7,771,000.44 m2 of containment works; 5 public squares; 2 sports courts; 3 soccer fields; 120 housing units; in addition to 1,465,000 new lampposts (numbers being updated).’’ According to the SMIH, “there will be an additional R$150 million invested in 5 communities.” The City did not respond in regard to the existence of reports with details on the execution and progress of these works.

The processes of the 21 works were open between 2013 and 2015, and the Rio Accounts Portal shows that the dates foreseen for the beginning of the 21 works were between July 1, 2014, and January 1, 2017, with the last work to be finished by February 10, 2020. That is, the works’ initiation was already planned before 2017, when Crivella was elected, and the end of the works scheduled for 2020. On the Rio Accountability Office website, the same works appear with dates that are slightly older, with work forecasted to begin by May 30, 2016, and to be finished by 2019. The two websites do not provide information on the results of these works.

The processes of the 21 works were open between 2013 and 2015, and the Rio Accounts Portal shows that the dates foreseen for the beginning of the 21 works were between July 1, 2014, and January 1, 2017, with the last work to be finished by February 10, 2020. That is, the works’ initiation was already planned before 2017, when Crivella was elected, and the end of the works scheduled for 2020. On the Rio Accountability Office website, the same works appear with dates that are slightly older, with work forecasted to begin by May 30, 2016, and to be finished by 2019. The two websites do not provide information on the results of these works.

“In reality, the Crivella government’s Strategic Plan does not create a single favela upgrading program, breaking the trend which we have seen since at least 1993, or prior if we consider Project Mutirão,” says Professor Adauto Cardoso, a researcher at the Metropolis Observatory. “This is just the utilization of resources that, per [the City’s] contract with the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB), have to be used for these works,” adds the professor.

Architect and urbanist Nuno André Patrício, author of a Master’s Thesis on this theme, on viewing the list sent by SMIH, explained: “these are the remains of contracts and a system of associated works that were already occurring. We look at this and see that the large part of these contracts are old, or are works of Morar Carioca or the development of PROAP [The Upgrading of Popular Settlements Program] III.”

Upgrading Programs

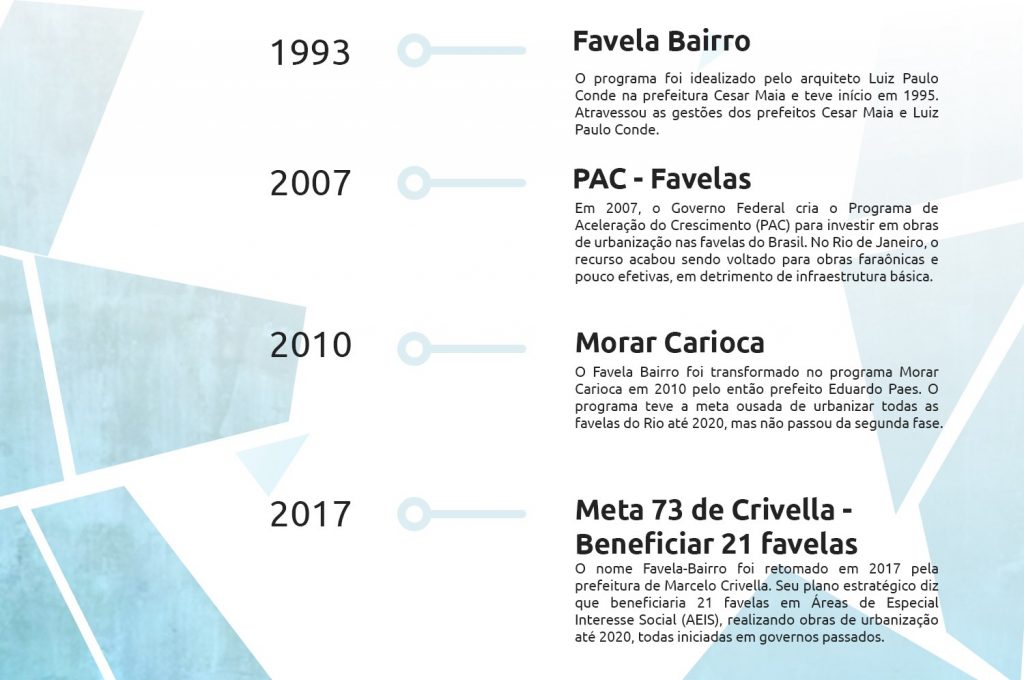

Three upgrading programs have marked Rio de Janeiro favelas’ 120 years of existence: Favela-Bairro/PROAP, PAC-Favelas (the federal Growth Acceleration Program as it was applied in favelas), and Morar Carioca. Favela-Bairro, created in 1993, lasted through the administrations of mayors Cesar Maia and Luiz Paulo Conde. “There was a continuity, during this period, of a work of upgrading, of constructing community equipment, of implementing infrastructure for sanitation, of paving roads, drainage,” explains Gerônimo Leitão, Director of the School of Architecture and Urbanism at the Fluminense Federal University (UFF), who also participated in Favela-Bairro’s projects as a consultant. In 1997, Favela-Bairro came to obtain the support of the IDB through the PROAP financing line.

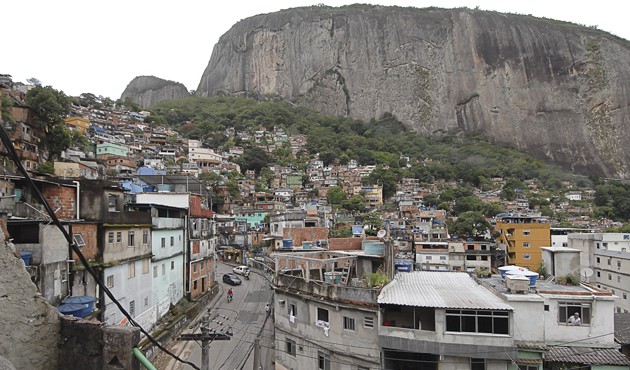

In 2007, the federal government created the Growth Acceleration Program (PAC) Favelas program with the aim of investing in upgrading works in Brazil’s favelas. “PAC invested the equivalent of an Olympic Games in all of Brazil, with more than 3,000 municipalities considered,” explains Nuno Patrício. According to an article published by the Metropolis Observatory, Rio de Janeiro was the city that received the most investment from the favela upgrading (component of the) program, with nearly R$3 billion (US$740 million) invested in 30 favelas or groups of favelas within the city. The municipality was the recipient of 70% of the resources designated for the state of Rio de Janeiro and almost 10% of the total resources invested in the country. The resources ended up being used for massive, high visibility works, to the detriment of the basic infrastructure still lacking in Rio favelas. Among these works were a cable car built to connect part of the favelas of Complexo do Alemão—inactive for the last three years, as of October—the elevation of the railway line in Manguinhos, and the construction of a footbridge overpass in Rocinha, designed by architect Oscar Niemeyer.

“In 2007, a cartel of companies was formed, and the project was influenced by this type of arrangement, with collusion from public powers. Today we know, [former governor Sérgio] Cabral is under arrest, all Cabral’s construction secretaries are under arrest, and these companies, Odebrecht, Quieroz Galvão, Andrade Gutierrez, Carioca Engenharia, etc., are under investigation. And of course, the residents resisted, and were able to stop at least the Rocinha cable car, which was already part of PAC II,” Patrício explains. It was at this time, he adds, that the contracts that lasted through various municipal administrations began, gaining different guises over time: “when PAC emerged, many things that were part of PROAP [Favela-Bairro], such as Vila Rica in Irajá, were handed over to the PAC.”

José Martins, 72 years old, has lived in Rocinha for the last 52. Martins began his involvement in community resistance in 1972, pushing for the implementation of a potable water network in Baixa da Rocinha. He says that the project, which was executed by the State, was approved, provided that Rocinha residents bought the material themselves. “After three years of fighting, we were able to buy the material. After that, I never stopped fighting. I have always been involved in the fight for our community,” said Martins.

According to Martins, with PAC I, a series of works began: “a daycare center, a family clinic, a UPA [primary health post], all had community participation; the idea for the works was widely discussed among residents. But PAC I ended, and it had not finished what it had promised to accomplish.” Already in the second phase of PAC, the government’s proposal was to build a cable car in Rocinha. However, residents took issue with this: “we needed to finish with sanitation first,” explains Martins. “We took to the streets, made posters, marched together, asking that the cable car not be built. What ended up happening is that the cable car wasn’t built, and neither was the sanitation. And nobody knows what happened with the money.”

“The big problem is that there is no public policy for the favela, there’s a moment where things are done, and then abandoned. There’s no conservation, maintenance, the public sector doesn’t care for what’s been done, it’s almost like a no man’s land, with just one-off works. There is no monitoring policy,” says Martins. “The government doesn’t accompany (the works), even if it listens a little bit to what the community has to say, and then abandons it. There was Favela-Bairro and other programs, but they do it and then leave it,” he questions.

Launched in 2010 under Mayor Eduardo Paes, Morar Carioca will likely be one of the major legacies of the mega-events held in Rio between 2014 and 2016. Nuno Patrício explains that the works of Morar Carioca were also works that had begun under the scope of other projects. “He presented Morar Carioca Phase I as a grand new program, but Morar Carioca Phase I was just capturing what was already being done. There were things that were underway, which were called Morar Carioca, but in reality, were also part of PAC. It was from PAC resources and it was given the ‘Morar Carioca’ plaque.” The researcher remembers that “Morar Carioca had a lot of paper, a lot of meetings, a lot of workshops, but there was little actual work being done.” With the ambitious goal of upgrading all of the favelas by 2020, in the second phase of the program, “few contracts were signed and the interventions did not comply with the timeline set forth in the original program,” explains a study from the Metropolis Observatory.

In 2017, the Crivella administration opted to abandon the name of the program from the previous mayor and used the name Favela-Bairro for the works which were still incomplete. Some of the bidding processes for the 21 favelas that were launched in 2013, in the second mandate of Eduardo Paes, were attributed to the program Morar Carioca, as materials from the government’s site show.

“It does not matter what the program is called, whether it is Favela-Bairro, Morar Carioca, or anything else. What is important is the maintenance of a consistent public policy for upgrading the favelas, a State policy. Independent of who is the manager, there ought to be a continuity of this policy. In situations of significant budget difficulties, if the rhythm is maintained, it can be expanded or reduced, which didn’t happen,” laments Leitão.

Patrício believes that a permanent and effective program is necessary, with the aim of attaining progressive improvements in favelas’ urban conditions. “There is no new formula or new agenda for favela upgrading. It is simply the remains of a ship that has not stopped sailing. One might give up command of the ship, but the ship keeps going. Favela upgrading is this: the ship will not stop immediately, but if we continue to do nothing, it will stop eventually,” says the architect.

The Future of Favela Upgrading

Around 22% of the population of the city of Rio de Janeiro lives in the 1,018 favelas around the city, according to data from the 2010 census. The municipality with the largest number of favela residents in Brazil, 1.4 million individuals, Rio still depends on collective construction and labor in order to guarantee infrastructure, housing, basic sanitation, and pavement for its residents.

“As a collective construction, any type of urban improvement undertaken for a (favela) territory must take into account that the territory has already been developed, that it was those people who built the territory in that way, who know where the sewage networks are, whether they’re precarious or not, how property distribution took place, how the lighting system is, where spaces of social engagement are. There is a logic to it, so the resources provided by (government) programs ought to be managed by those who are already there. This is a paradigm that needs to change, the resources are not managed by that population. The resources come from the federal government, the bank, stay with the Secretariat and amongst the public organs,” argues Patrício.

A member of the Rio de Janeiro Architecture and Urbanism Council (CAU/RJ), architect Tainá de Paula explains that it is important for the population to embrace an agenda of upgrading, “people have a lot of difficulty organizing themselves to discuss the urban agenda because there was a stripping of spaces for collective participation, the Cities Council and the Housing Council were spaces intoxicated by a logic of political and institutional evacuation. The relations that we had did not strengthen the tension and the popular debate, the hollowing-out was deliberate.” For her, the councils were not able to serve as an adequate bridge with civil society, which made people lose connection with institutional agents, with political power, and with a form of operating and setting agendas for the territory.

De Paula, who also coordinates BR Cidades Rio de Janeiro, tells that they are creating a “Program for Popular Planners” to “promote the inverse: to have more urban provocateurs, urban organizers, and more engaged actors. The program is basically a qualifying course for leaders of popular territories and favelas, for debating urban agendas and public policy.”

“I think this is fundamental, that if you are able to activate people to have this kind of talk and discourse in the territories, then it will become much easier when (Mayor) Crivella knocks on the door of a determined favela and says, ‘I am going to upgrade this here,’ and (already) have a subject (ready to) respond with, ‘hey listen, what about the plan and the budget?’” she jokes.

How is work going in your favela?

The difficulty of finding information regarding upgrading works that are occurring in the favelas of Rio de Janeiro in the past few years spurred data_labe to create a collaborative map.

The map has 21 points distributed in favelas that had works concluded between 2017 and now or are in progress through 2020, according to the administration of the Mayor Marcelo Crivella. We began with the information made available publicly by the City and on the Rio Accounts Portal. Now we need your help to learn about the progress and effectiveness of these works! Do you have upgrading work occurring in the favela where you live? Collaborate with us on the map!