This is the first article in a series of four, based on a study into the disciplinary processes that took place in the lead up to, during, and following mega-events in Rio de Janeiro. The series uses the experiences of the favelas of Babilônia and Chapéu Mangueira, using the theme of discipline as categorical analysis, splitting the theme into three dimensions: physical, economic, and symbolic. This series of articles is based on a scientific paper originally published in the journal CITY in December 2018. Read the full paper here.

The study references data on Rio de Janeiro public policy as well as interviews undertaken between 2014 and 2019 in Babilônia and Chapéu Mangueira favelas. Names of residents interviewed were not released.

Introduction: The Transformation of Rio Favelas through Discipline

The years leading up to the World Cup and the Olympic Games were characterized by optimism in many Brazilian cities: more investments in urban infrastructure, housing, services, entrepreneurship everywhere; a huge influx of new people, money, projects, and hope. The country seemed to be changing, not only because of the sporting events themselves, but because of a general sense of stability and development that had been in the air for a few years.

However, this was just one side of the coin. In the most vulnerable neighborhoods and settlements, removals, police violence, and rising property prices manifested in socio-spatial reconfigurations coercing and pushing black, migrant, and low-income communities away from the most desirable areas of cities. In Rio, this process was even more acute in the South Zone favelas, whose privileged locations in the urban fabric became a peculiar catalyst for new urban phenomena.

And what are these new urban phenomena? With the arrival of new actors, interests, and investments in large Brazilian cities, the dynamics present in low-income and peripheral neighborhoods have also begun to change. In recent years, for example, the term “gentrification,” which for decades was associated with the market expulsion of low-income groups from European and American neighborhoods, has also become part of the favela lexicon. Rio de Janeiro is not a pioneer in this sense, as reports of gentrification appeared in the early 2000s in other Brazilian communities and states (note the case of Pelourinho, in Salvador, Bahia), however, Rio seems to have been one of the most emblematic cases when it comes to gentrification in favelas. Especially in the city’s South Zone, communities such as Santa Marta, Vidigal, Babilônia and Rocinha all underwent sudden transformations, where real estate speculation, tourism, and police control came together in a powerful entanglement of forces. The consequences reverberate to this day.

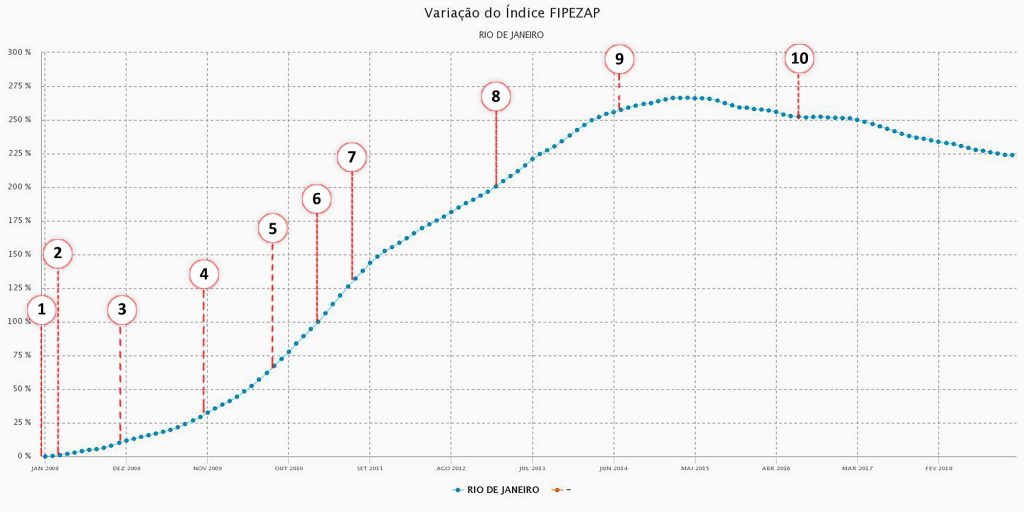

Some of the iconic events affecting Rio’s favelas as associated with fluctuating real estate prices in the city (see above chart):

- October 2007: Brazil is confirmed as host of the 2014 World Cup.

- March 2008: The first Growth Acceleration Program (PAC) works begin in the favelas of Complexo do Alemão, Manguinhos, and Rocinha.

- November 2008: Inauguration of the first Pacifying Police Unit (UPP) in Santa Marta, in the South Zone.

- October 2009: Rio de Janeiro is confirmed as host of the 2016 Olympics.

- July 2010: Launch of the Morar Carioca favela urbanization program.

- February 2011: Morar Carioca works begin in the Babilônia and Chapéu Mangueira favelas.

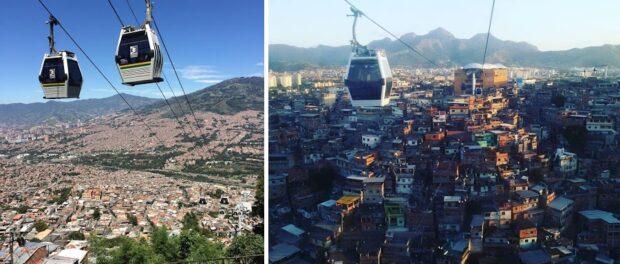

- July 2011: Inauguration of the cable car in Complexo do Alemão.

- March 2013: Local government delivers sustainable housing building units built as part of Morar Carioca Verde in Babilônia.

- June/July 2014: World Cup. Much of pacified South Zone favelas are already full of tourist hostels and bars.

- July 2016: Olympics. Consolidation of most works as part of the mega-events season in Rio de Janeiro.

Agents and Forces in Favela Transformation

Firstly, it is essential to emphasize that the pacification policy, prior to the mega-events, was a major factor for cultural and socio-spatial transformations in favelas. Also, it is important to note that its implementation, approach, and consequences varied among Rio’s diverse favelas and cannot be fully generalized. However, there seems to be a clear rise and fall: at present, the Pacifying Police Unit (UPP) model appears to have entered a process of decay, especially following a boom in drug-trafficking and drug-wars since 2017. But at the beginning (and especially in the case of the South Zone), the UPP project was sold as a permanent State presence for the favelas, one that would bring order and the force of the law.

The sense of security and the “exotic” image of favelas boosted tourism, which was promoted by both outsiders and residents (community-based tourism). In addition, hostels, art galleries, restaurants, trendy bars, and nature trails spread through many of Rio’s favelas, especially those with the most privileged views.

Urban projects literally paved the way for this process. Part of a succession of urban upgrading policies that began in the 1990s (notably, with Favela-Bairro), projects such as the Growth Acceleration Program (PAC) and Morar Carioca included interventions focused on attracting investment, visibility, and tourism for the favelas. The most emblematic examples of this process came in the form of cable cars and lookouts installed in favelas, largely inspired by the success of Medellín, Colombia.

Finally, the presence of private investment played a key role in this process, whether in the form of small-business entrepreneurs who leveraged their business in the favelas, or in the form of large contractors and international organizations, which have seen in the favelas fertile ground for new ventures.

In short, it is this tangle of forces and interests that has recently been molding many contemporary favelas. The legacy of these initiatives is uncertain and volatile, but it has left its mark. To be palatable, legible, and legitimate for external consumers, it was necessary to discipline the territories and their residents. After all, favelas were long perceived as places of disorder and marginality. But how do residents perceive these disciplinary processes? Obvious at times, subtle at others, they remain latent, ready to re-engage in the commodification of these territories.

In this context, in order to better understand the rise and fall of such phenomena and their effects on residents, we used reports from the residents of Babilônia and Chapéu Mangueira—both favelas extremely vulnerable to the city’s real estate pressures—as an emblematic case study.

In this four-part series for RioOnWatch, we will deal with the forces that operated and still operate in South Zone favelas, using Babilônia and Chapéu Mangueira as reference cases. As a category of analysis, we approach the topic of discipline in three important dimensions: physical, economic, and symbolic. This introductory text sought to provide context for the disciplinary processes and phenomena that drove socio-spatial transformations in South Zone favelas. In the next article, we will address the subject of physical discipline, using the voices of residents and their experiences as a starting point for our analysis.

Eric Chu is a lecturer in Planning and Human Geography at the School of Geography, Earth. and Environmental Sciences at the University of Birmingham.

Isabelle Anguelovski is founder and director of the Barcelona Lab for Urban Environmental Justice and Sustainability. She is a Research and Advanced Studies (ICREA) professor at the Autonomous University of Barcelona, at the Institute of Environmental Science and Technology (ICTA), and at the Hospital del Mar Medical Research Institute (IMIM).

Thais Cosmelli holds a PhD in urbanism and is a researcher at the Post-Graduate Program for Urbanism at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ). She is a visiting researcher at the Development Planning Unit at University College London.