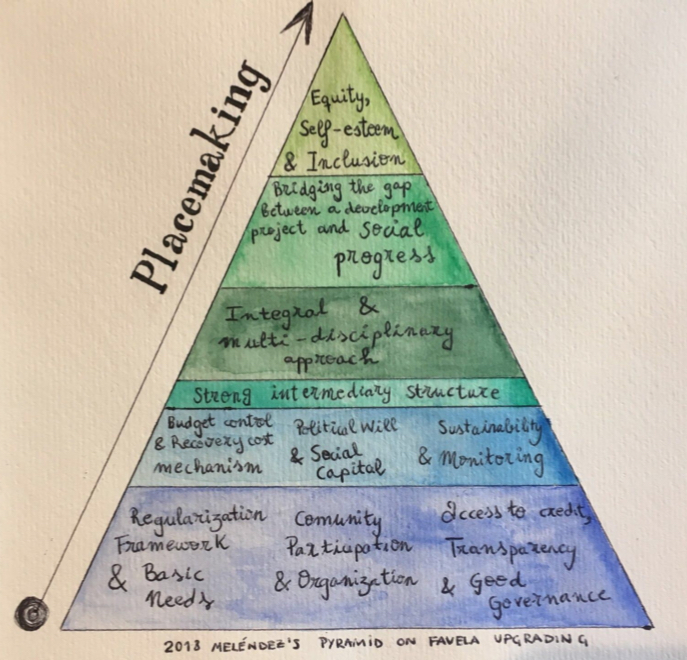

This is the first article in a six-part series on the application of Meléndez’s Pyramid for Favela Upgrading to the city of Rio de Janeiro and its favelas. This pyramidal concept was conceived by the author of this series as a proposed methodology to achieve more coherent and sustainable results in favela upgrading. Inspired by Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, the pyramid consists of ten blocks, each representing a group of indispensable elements. Essentially based on multidimensionality, interdependence, and simultaneity, the pyramid addresses the physical, political, economic, social, cultural, and psycho-emotional aspects of favelas.

This first article is an introduction to Meléndez’s Pyramid for Favela Upgrading, which acts as an invitation to rethink informality, reject urban antagonisms, and acknowledge the strengths and potential of favelas. Read the full series here.

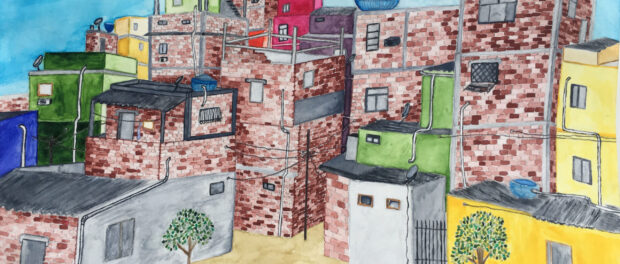

With approximately 24% of its residents living in favelas, Rio de Janeiro is often seen as a dual city, split between formal and informal. Poverty and deprivation, socio-spatial exclusion, stereotyping and neglect, lack of empathy and acknowledgment of favelas’ unique social capital, privatized politics, oligarchic neoliberal urban and real estate policies, and a militarized police force make this one of the most polarized urban contexts in the world.

Bouts of favela clearing and resettlement to distant, under-serviced land, as well as deep-rooted stigmas marking favela residents as “sub-citizens” in urban imaginaries, have led to both an experienced and figurative marginalization of informal areas. The result is a heavily toxic urban dynamic. To begin unraveling this reality, the city must reconcile and surpass its dichotomous approach to favelas.

Dyads such as formal-informal and legal-illegal denote a simplistic, inaccurate and hierarchical juxtaposition that deprives, marginalizes and dehumanizes favela residents. Rather than a legitimate dichotomy, Rio’s formal-informal duality is a trap leading to misguided policy efforts in the best of times (and intentionally harmful policies in the worst of times). To untangle policy dichotomies and sectorialism, this six-part series proposes a multidimensional, integral approach to Rio’s favelas: a pyramidal concept that aspires to consider the multitude of physical/physiological, economic, social, political, cultural, psychological and emotional dimensions of favelas.

As many activists argue, a favela é cidade or, “the favela is the city.” What is designated as “informality,” is very much part of the formal system, though marginalized by it. The “favela” and the “city” are interdependent. Even while ensnared in cyclical poverty, favela residents make at least four contributions to the city’s economy. First, they invest in housing and land improvement. Second, they integrate into the job market—most often at highly favorable rates for employers. Third, countless small businesses in favelas allow for high-velocity monetary exchanges. And fourth, their communities generate invaluable social capital. This way, favelas partake, to their disadvantage, in capital accumulation and “formal” city systems.

Informality often fills in gaps caused by the shortcomings of the formal system in meeting basic needs. Meanwhile, citizens of informal settlements have historically been those responsible for building and maintaining the city. Therefore, instead of dehumanizing and marginalizing, one should acknowledge their resourcefulness, recognizing favelas as another, equal part of the metropolis. This is all the more crucial given that favelas may hold the key to unlocking future sustainable development.

Almost universally, around the world, urban policy approaches favor the wealthy and neglect low-income populations. A 120-year-long policy of active neglect towards favelas has been maintained not separate to, but critical to, the parallel development of a luxurious Rio, manifest in the Sheraton Hotel below Vidigal, the sumptuous residences of São Conrado adjacent to Rocinha, and the upper-class neighborhoods concentrated in the city’s South Zone.

Imagine the potential were Rio to champion the whole of its citizenry. As argued by Ananya Roy, Arturo Escobar, and Teresa Caldeira, among others, when citizens are placed at the epicenter of city planning, urban services have the power to create social cohesion and progress. Urban policy must thus be centered on Rio’s favela residents, addressing the challenges and enhancing the strengths of each favela.

Likewise, speaking of “favela integration” can also be viewed as paternalistic, presuming favelas are not already integral to the city and that “integration” means finding ways to make favelas behave and look like elsewhere in the city. Favelas are already part of the city. What their residents lack is equity, respect and investment. The role of public authorities, therefore, is not to integrate, but to provide an equal footing for favela residents to lead dignified lives. In this same vein, favela upgrading should not aim at “formalization” or homogenization. Rio should aim to achieve zero poverty and full equity and inclusion while maintaining the core of the Carioca essence derived from the city’s diversity. In short, Rio’s spirit is held within its favelas.

With informality rethought, favelas can be recognized for their potency. This means residents are provided with the welfare, opportunities, and freedoms to enable them to attain their aspirations. Otherwise, the neglect and continued active undermining of Rio’s favelas will prevent urban progress.

The aim of this series is to recognize the potential of favela upgrading actions undertaken in Rio. In a previous in-depth study and analysis of over 40 favela upgrading projects across Latin America, the author extracted a series of fundamental elements for comprehensive favela upgrading, organizing them in a pyramid. Inspired by Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, Meléndez’s Pyramid for Favela Upgrading consists of ten blocks, each representing a set of crucial elements for upgrading interventions. All pyramid blocks carry equal importance: the pyramidal shape and distribution merely denotes logical order in implementation (from the bottom up), not hierarchy.

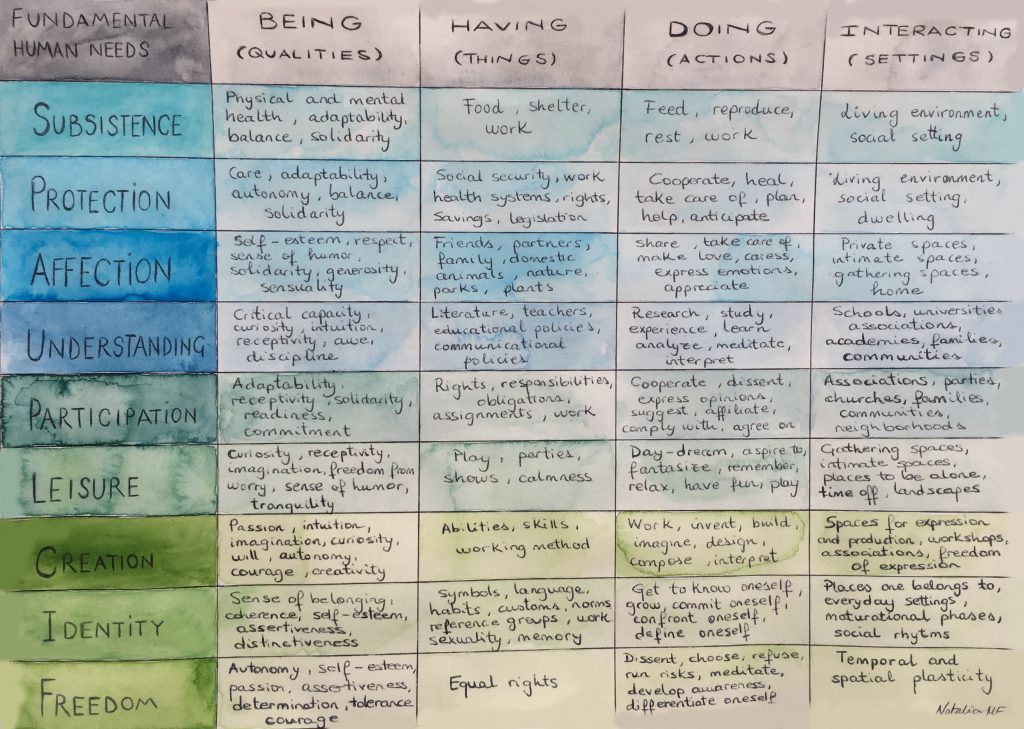

As a result, our pyramid proposes a set of vital elements for favela upgrading, designed to meet the widest array of anthropological needs. Drawing from Chilean economist Manfred Max-Neef’s taxonomy of fundamental human needs, we advocate for a favela upgrading framework that addresses physical/physiological, economic, political, social, cultural, psychological and emotional needs, all of which are interconnected and interdependent.

Rejecting one-size-fits-all solutions, our pyramid promotes bottom-up favela upgrading in a framework that permits meeting and prioritizing the specific needs of each location. Satisfying residents’ needs requires integrated and multi-disciplinary upgrading of favelas. Regularization, basic services, political will, good governance, and sufficient credit are all important components for further action.

Finally, any intervention should advocate for cooperation among diverse stakeholders, prioritizing true community participation at all stages. By introducing a strong intermediary structure in the Pyramid, transparency is facilitated and budget control, cost recovery, and monitoring processes can be streamlined. This paradigm shall adopt economic, sociocultural, and psycho-emotional development strategies, with a special emphasis on social capital, equity, self-esteem, and inclusion. Together, these elements enable us to bridge the gap between typical development projects and actual social progress—a key guarantor of sustainability.

As shown by our pyramid, favela upgrading must reinforce favelas’ roles in “placemaking.” As formulated by architects Lynda H. Schneekloth and Robert G. Shibley, “placemaking” is “the way in which all of us as human beings transform the places in which we find ourselves into places in which we live.” If the places we inhabit shape us, then upgrading has far-reaching socio-political functions. This echoes urbanists Mostafavi and Doherty’s metaphor of urban planners as “doctors of the city.”

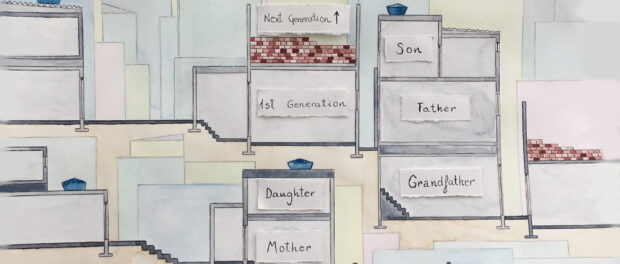

Melendez’s Pyramid aspires to link the fulfillment of anthropological needs with the identity and potential of each favela, celebrating them in their diversity. In parallel, this pyramid is an acknowledgment of the home and its surrounding community as the locus of all development. Its ten blocks, each embodied by existing practices in Rio, are detailed in the next five articles.

This is the first article in a six-part series.

Natalia Meléndez Fuentes is an MSc candidate in Building and Urban Design in Development at the Bartlett Development Planning Unit at University College London. Her research looks at the psycho-emotional elements of favelas and favela upgrading, mainly in Latin America, and how to bring these to the fore.