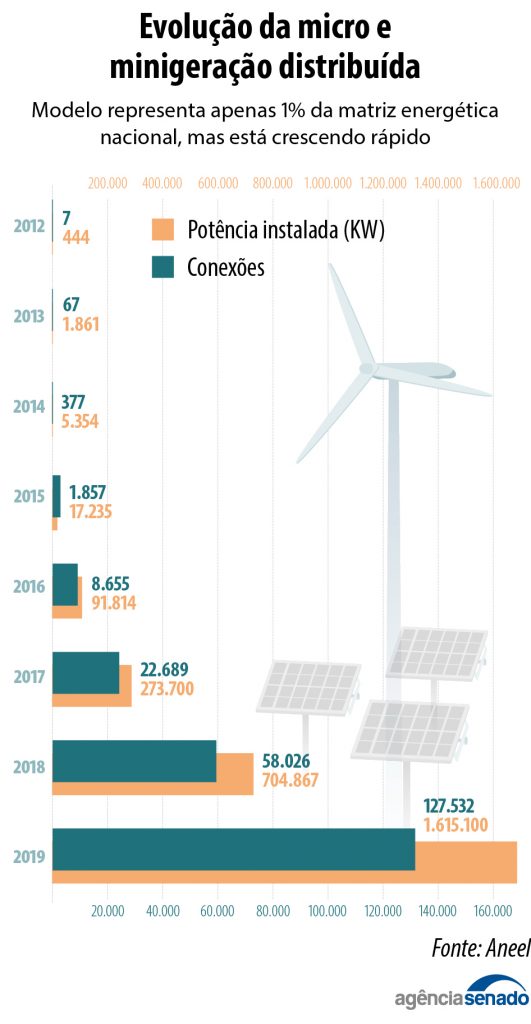

Contrary to global efforts towards sustainability and cleaner energy, Brazil’s National Electric Energy Agency (ANEEL) has proposed changes to 2012’s Normative Resolution 482 that will raise costs for consumers who produce small amounts of solar energy. The standing resolution regulated distributed microgeneration as a way to encourage energy generation from renewable sources, solar energy in particular.

Distributed microgeneration is small-scale local production where surplus energy produced by the consumer is released into the conventional electric grid to power other homes and businesses in the area. In exchange, the distributor returns this energy at no cost to the consumer to use at times when they are not producing energy (at night or on cloudy days, for example) or provides credits that can be used to reduce the consumer’s other energy costs. The importance of distributed generation is that it creates a financial incentive for consumers to recuperate their initial investment in solar panels more quickly.

In Brazil, there are some, though limited, public and private lines of financing for the acquisition and installation of solar equipment, such as BNDES Finem – Power Generation for businesses, at below-market interest rates, and the Construcard from the Caixa Econômica Federal Bank, for residential projects. One bill, Senate Bill 371, aimed at allowing the use of resources from the FGTS workers’ fund for this purpose, has been stuck in the Senate since 2015 without ever being approved. In addition to credit for implementation, there is still a need for public policies to support research and professional training for working with renewable energy.

In October of 2019, ANEEL began discussing the taxation of this returned energy at up to 62% of its market value by charging a Tariff for Distribution System Use (TUSD). This rule would apply gradually to local self-consumption, and immediately for remote self-consumption. The argument behind the change is first, that the distribution of energy involves other costs beyond the energy itself (for example, the installation and maintenance of the power grid), which would then burden other consumers who do not produce their own energy, and second, that the subsidies have already served their function of stimulating the sector and encouraging solar energy use. Additionally, in ANEEL’s proposal, distributed generation would now pay subsidies for thermoelectric plants and also losses avoided by photovoltaic systems.

However, only 1% of Brazil’s energy matrix currently comes from distributed microgeneration, benefitting only 0.2% of consumers. This in a country where sunlight is an abundant resource. On average, there is 30% more sunlight in Rio de Janeiro than in Germany’s major cities; still, Germany produces 7% of its energy from solar sources (36% of its entire energy grid is renewable).

In addition, it is estimated that the proposed change in the Resolution will lead to a 25% increase in the time required to recuperate the initial investment of installing a photovoltaic system. According to the director of ANEEL, this will mean an increase from the current 4.5 years, to 7 years. According to University of California Los Angeles (UCLA) economics professor Rodrigo Pinto, on the other hand, the increase in the timeline for returns on investment in distributed solar generation will be over 20 years.

The Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office itself considered the charge to be excessive, notifying ANEEL and recommending that the fee implementation should be gradual, as the share of participation in the solar energy matrix continues to grow. Moreover, 303 deputies and 31 senators produced a document asserting that these changes should only occur once distributed generation levels make up 5% of the national electricity matrix. In California, for example, subsidy decreases only began when the share of distributed solar generation reached 5% of the energy matrix, and even then it was determined that the tax on returned energy would be set at only 10% of the regular price.

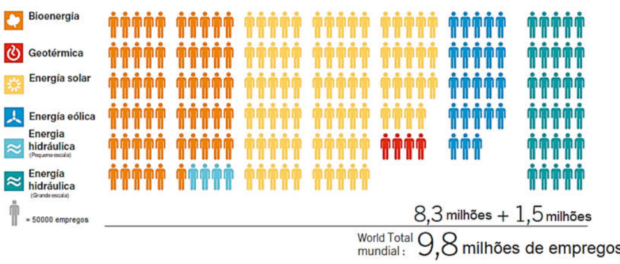

For industry advocates, there are innumerable benefits that justify maintaining industry incentives for solar energy. They assist in the transition to a cleaner, renewable, and decentralized energy source that does not harm the climate, ecosystems or Brazilian forest peoples. Moreover, they promote energy security through the diversification of the energy matrix (hydropower, for example, has a large dependence on climate-related events such as droughts), the creation of jobs (as compared to other sources), and the reduction of electrical losses (these are energy losses which happen over the many miles that the energy travels from hydroelectric or thermoelectric plants to households. These losses are borne by the end consumer, as opposed to in distributed generation, in which surplus energy is distributed locally).

Energy insecurity has a direct impact on rising energy prices: the red flag on electric bills is the result of low level water reservoirs. Thermoelectric energy charges even more, and besides being more expensive, pollutes more.

Subsidies for solar energy development strengthen and expand solar supply from this energy source, which is cheaper, and thus have the potential to reduce costs for consumers over the long run. For all of these reasons, Argentina aims to have 20% of its energy come from renewable sources by 2025. In Chile, solar energy and wind power are already cheaper than coal.

Critics of ANEEL’s proposal argue that ANEEL’s role as a regulatory agency is to monitor products for the benefit of the consumer, not suppliers and distributors.

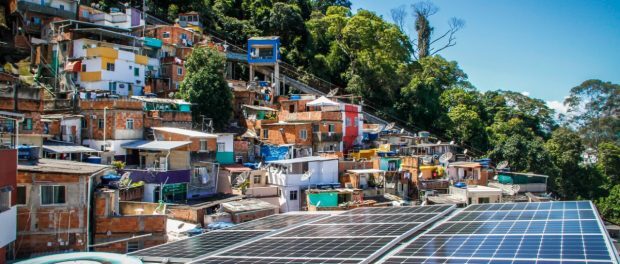

Impacts on Potential of Favela Solar

The change in the resolution could mean serious setbacks in the use of solar energy in favelas, which is still mostly in the experimental stage. With this in mind, 40 organizations involved with the expansion of solar energy in Rio de Janeiro’s favelas signed a letter calling attention to the absence of a preliminary impact study for this proposed legal change, assessing its effect on low-income families. For these families, the savings on their electric bills is extremely important, especially as they live in places that are subject to abusive charges and an irregular power supply.

Among these organizations are RevoluSolar, a community-based non-profit association that produces and researches renewable energy in Morro da Babilônia and Chapéu Mangueira, favelas in the South Zone of Rio de Janeiro, and Insolar, a social business that offers low-cost financing programs for residents that buy their own solar panel systems. These and other organizations are all part of the Sustainable Favela Network (SFN), which has also signed the letter. SFN is an initiative launched in 2017 by Catalytic Communities (CatComm)* to recognize, support, strengthen, and expand on the sustainable qualities and community movements inherent to Rio’s favelas. As the letter highlights, a survey conducted by SFN community initiatives at the end of 2019 concluded that 85% of the favela-based community organizations with their own headquarters said they wished to install solar panels and be proactive agents of change promoting solar energy in their communities. This was the highest percentage of various sustainable technology options on the survey, demonstrating the untapped potential that now runs the risk of remaining untapped due to the proposed changes.

The initiatives realized by these organizations in favelas play an important role in making solar panel technology accessible (for example, by facilitating access to credit, hard to acquire by informal businesses or individuals without property titles, or by fundraising). Solar panel technology has a high initial cost, but contributes to a reduction of monthly energy costs and to the regularity in energy supply, as well as training residents for the job market in this sector. The money saved can be applied to other priorities, such as education and housing improvement. A concrete example given in the letter is the savings of nearly R$7000 (US$1700) annually by the Favelas Observatory, an organization based in Maré, in the North Zone, which is now directing these savings towards professional education projects.

The submission of the letter was part of a public consultation process conducted by ANEEL, which closed on December 30, 2019. Previous changes to the Resolution included contributions from consumers and civil society. For example, in 2017, changes in the definition of microgeneration were approved after almost a month of public hearings, which saw 91 contributions from 51 actors, among them distributors, consumers, consumer advocates, and associations, showing the importance of hearings and other forms of public participation, such as sending letters to federal deputies. It is expected that these contributions and other efforts are taken into consideration before approving the final version of the Resolution.

Finally, despite a basic public subsidy being necessary, this distributed generation model ultimately results in little dependence on public investments to function, allowing for the redirection of government resources to research and development for technology, making solar energy more efficient, competitive, and financially accessible. In addition, other successful options have been tested in other countries, including government subsidies to make purchases of photovoltaic energy cheaper than other forms of energy for all consumers, the reduction of production and consumption taxes, and guaranteed State purchase of surplus production.

→ Recommended Follow-Up: Response to Federal Proposal Harming Solar in Brazil from 40 Organizations Developing Solar Energy in Rio Favelas

*The Sustainable Favela Network and RioOnWatch are both projects of Catalytic Communities.