This is the latest contribution to our media watchdog series on the Best and Worst International Reporting on Rio’s favelas, part of RioOnWatch’s ongoing conversation on the media narrative and media portrayal surrounding favelas.

We tend to open this column rebuking international correspondents for, year after year, focusing exclusively on violence in Rio de Janeiro’s favelas. We have repeatedly explained how this sort of negative coverage contributes to imbalanced, negative stigmas surrounding favelas, and that such media-perpetrated stigmas reinforce a historic narrative that in turn generates support for punitive and equivocal public policies that ultimately lead to more human rights abuses, and generate only greater violence and inequality in Rio de Janeiro. This year was proof, with the public electing a government primarily on its promise to double down on hardline actions towards favelas.

Thus in 2019, Rio de Janeiro police killed more people than they had in any past year on record. Stoked by hardline rhetoric from newly-elected Governor Wilson Witzel, Rio security forces killed with the confidence of near-guaranteed impunity. In this context, the relentless waves of bloody headlines flooding international coverage of Rio favelas were warranted and necessary; effective journalism must hold public officials accountable for their words and actions. However, we at RioOnWatch continue to insist that solutions-based, pro-positive reporting is imperative to deconstructing violent and inaccurate stigmas surrounding favelas and that Rio will only be relieved of its toxic reality and begin to realize its potential through widespread deepening of such perspectives.

The focus on State-sponsored violence may have led correspondents to miss some of the biggest positive stories coming out of Rio favelas last year. Why didn’t we see, for example, coverage of Complexo do Alemão’s Lucas Lima, who, at 24, built his own low-cost 3D printer. Or the Unifavela college entrance exam prep course in Maré that had 100% of its students accepted into university. Or more on the fight to bring solar energy to favelas across Rio. The peripheries of Rio continue to produce innovative solutions to modern challenges, and we do the world a disservice by ignoring the potency of these territories.

Still, 2019’s unprecedented police violence required unprecedented attention. In that light, foreign correspondents and international outlets played a central role in monitoring and questioning Rio public security policies.

Important Work Covering Police Violence

Witzel’s ultra-violent discourse (including: vows that police would shoot criminals in “their little heads;” toying with the idea of sending a missile to blow up City of God; repeated appearances in uniform; and a machine-gunning helicopter trip) featured prominently alongside a string of horrific accounts of police violence. The killing of 8-year old Ágatha Felix, a massacre in Fallet-Fogueteiro, the 257 shots fired at the car of musician Evaldo Santos, the shooting of Brazilian jiu-jitsu instructor Jean Rodrigo Aldrovande, and a string of unarmed youth caught by “stray bullets” all roused international correspondents to produce excellent, meaningful reporting. The best of these articles highlighted residents’ voices and critically examined official police statements:

- The New York Times: “‘They Came to Kill.’ Almost 5 Die Daily at Hands of Rio Police.” Combining testimony from victims’ family members, interviews with activists and NGO leaders, and statements from public defenders and lawmakers, this article takes a 360° look at the records being set by Rio police.

- BBC: “14:30 in Rio. The story of a death.” This beautifully, sincerely told long-form piece traces the life and death of jiu-jitsu professor Jean Rodrigo, placing his killing in the context of new trends in police violence.

- The Guardian: A series of excellent pieces including up-close follow-ups with the families of victims of the Fallet-Fogueteiro massacre (“‘It was execution’: 13 dead in Brazil as state pushes new gang policy“) and Ágatha Félix case (“Brazilians blame Rio governor’s shoot-to-kill policy for death of girl,”) with actual reference to this as a “genocidal” policy from Alemão community activist Thainã de Medeiros. Meanwhile, “‘Caught defenseless in the crossfire’: Rio families cope with deaths by police violence” is a deeply moving interview with the husband of the late Margareth Teixeira, a 17-year-old mother shot by police in the West Zone neighborhood of Bangu.

- The Washington Post: “As police shootings in Rio rise, children are caught in the crossfire” digs into the stories of children hit by stray bullets in police operations this year, pairing ministry of health data with family interviews. “Soldiers in Brazil fired dozens of shots at her family, killing her husband. Will anyone be held accountable?” provides a crucial follow-up to the killing of Evaldo Santos. As the court case draws on months later, military members involved have begun to change their story.

Other, thematic pieces did well in conducting wide-spanning interviews with residents, community leaders, and public officials. This broad AP piece on the city’s divided opinion over violent policing methods does just that, clearly establishing the strategy’s human cost. Others, such as these in-depth pieces from The Financial Times and Bloomberg dug deep into the increasingly critical topic of Rio’s growing militia groups.

Special recognition goes to this excellent op-ed piece for The Washington Post, “Another fire is raging in Brazil — in Rio’s favelas.” Also, the months-long bullet-casing analysis conducted by The Intercept in partnership with NGO Sou da Paz and the Swiss Small Arms Survey research group effectively demonstrates the international scope of Rio’s armed conflict.

Though not favela-specific, several other articles did well in providing political background for Rio’s violence. This Al-Jazeera piece traces the origins of 2019 policing through the legacy of Rio’s 2018 military intervention. And former RioOnWatch collaborator Stephanie Reist effectively situates the State’s mix of bloody policing and militia involvement in a framework of necropolitics for Jacobin Mag.

Last, this piece for the April 2019 issue of The New Yorker may be the single most comprehensive write-up on Jair Bolsonaro’s Brazil to date.

And Yet…

Some fell short. An otherwise brilliant Washington Post article fell apart with a single sentence when it stated that Witzel’s “crackdown might be showing results. Rio’s homicide rate fell 24 percent in the first two months of the year, government figures show.” The unsubstantiated claim (draped in a “might”) undermines the article’s greater purpose, egging on a false causation that has been widely debunked by public security experts, both in relation to President Jair Bolsonaro’s policies on the national level and Witzel’s actions on the state level (see here, here, here, here, and here).

Other publications have continued to glorify the police, fawning over movie-style tactics and war technology, as in this bizarrely-idolatrous CBN piece on Rio’s BOPE elite police force, in which the Christian news team “traveled into a favela with them for a training mission – it’s a safer neighborhood because they’ve already cleared it. But you can see the tactical way they learn to move, because you don’t really know who the bad guys are until they are shooting at you.”

Best Reporting on Favelas in 2019

Thankfully, positive stories were not entirely lacking last year. And neither was coverage keeping a spotlight on the political assassination of Marielle Franco or reminding audiences of the critical neglect of public services in favelas.

The Arts

- The Economist: “Female MCs are changing Brazilian funk music.” This boldly atypical Economist article shines a light on the feminist side of often machista funk music, portraying the movement against the background of Brazil’s conservative backlash.

- The Conversation: “Sex, drugs and feminism: for Brazil’s female funk singers, the personal is political.” Written by a Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ) professor re-addressing her assumptions about funk through anthropological fieldwork, this thoughtful article delves into the socially liberating power of funk’s feminist artists.

- Afropunk: “The Rise and Fall of Baile Funk DJ Rennan da Penha.” What begins with a vivid description of Complexo da Penha’s now-defunct baile da gaiola party eases into an in-depth and analytical take on the cultural battle over funk and the political implications behind the arrest of DJ Rennan da Penha.

- Hyperallergic: “The Grassroots Film Movement Growing in Rio de Janeiro’s Favelas.” If you haven’t heard of Rocywood, Rocinha’s burgeoning independent film scene, start here.

- The Rio Times: “Exhibition Favelagrafia 2.0 Unveils Creative Powers of Rio de Janeiro’s Favelas” covers the Museum of Modern Art’s (MAM) favelagrafia showing, an exhibit realized with the stated aim of displaying “the favelas through the eyes of their residents.

Marielle, One Year Later

- The Guardian: “Marielle and Monica: the LGBT activists resisting Bolsonaro’s Brazil.” This mini-documentary follows Franco’s widow, Mônica Benício, focusing on the less covered aspect of the couple’s LGBT activism and Benício’s continued advocacy following Franco’s death.

- The New York Times: “A Year After Her Killing, Marielle Franco Has Become a Rallying Cry in a Polarized Brazil.” This short piece combines close personal interviews with new findings on Franco’s murder, framing the late city councillor’s death within 2019’s social milieu.

- Open Democracy: “The life and battles of Marielle Franco” is both intimate and comprehensive, drawing from both the history of Rio’s favelas and the author’s personal relationship with Franco.

- Americas Quarterly: “After Marielle, These Black Women Are Changing the Face of Brazilian Politics.” This article on the rise of black women politicians from the favelas in the wake of Marielle Franco’s assassination shares hope from the next generation of Marielles.

Favela Services and Public Policy

- France 24: “With our Observers in Rio de Janeiro: favelas, beach clean-ups and more.” One of the series’ “observers” is a doctor from Instituto Movimento e Vida. This is a great look at her efforts to expand access to physiotherapy in the North Zone favela.

- INews: “‘We’re real people too. And besides, drug lords still want to receive the post’: Delivering letters to Brazil’s labyrinth of favelas.” We’ll forgive the title, as the article itself is a careful and unique telling of one group’s work to ensure mail delivery in Rocinha.

- Wired: “Rio’s Defunct Gondola Tells a Tale of Transit Style Over Substance.” Published just as Witzel announced a goal to re-open the line by year-end, this well-timed follow-up to the 2016 closing of Complexo do Alemão’s cable car merges resident perspectives, international comparisons, and usage data.

- Rio Times: “Instead of Favelas, Luxury Condos Could Soon Stand on Rio’s South Zone Hillsides” does a good job of breaking down a complicated but important City bill that would deregulate new housing construction, potentially opening the door to further favela gentrification.

Two articles for Catholic Philly and the Jesuit America Magazine deserve note for delving into the history and current role of the Catholic Church in serving the favelas. The former, despite its clickbaity title—”Slum Jesus to be part of Rio de Janeiro’s Carnival in 2020“—gives an opening look into the Mangueira Samba school’s efforts to retake Jesus’ legacy from the Christian right.

There was also an interesting unexpected dispatch from Iowa’s The Scarlet and Black, covering a collaboration between Maré activist Henrique Gomes da Silva and Grinnell professor Nick Barnes.

Last, we were taken aback by this remarkably progressive favela food tour undertaken by Youtuber Mark Wiens. With a tone that ranges from genuinely curious (clueless at times) to sincerely grateful, Wiens manages to destigmatize without falling into the trap of romanticization.

Worst

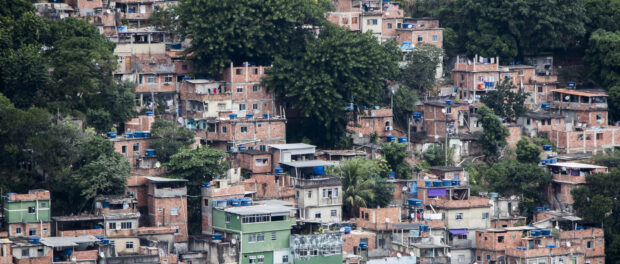

The worst articles on Rio favelas trumpet the same old tropes. As RioOnWatch continues to urge publications away from the stigmatizing and inaccurate translation of “favela” into terms such as “slum” and “shantytown,” mainstream and fringe publications alike have stubbornly protected their style guides. In the best cases, these translations read like wince-worthy blips in otherwise stellar reporting. In the worst cases, they are symptoms of the writer’s glaring unfamiliarity with favelas. The following articles fall into the latter category, treading ground somewhere between intellectual dishonesty and condescension.

When a boozed-up Australian tourist decided to wander into the hills of Morro do Adeus in Complexo do Alemão, the Daily Mail Australia jumped in, explaining that “A favela is a crime-ridden slum, or ‘shanty town’, in Rio de Janeiro which is home to 1.5 million people from low-income households. Favelas lay on the outskirts of the city, and have long been dominated by gangs who traffic illegal drugs.” The text, surrounded by party pics of the Australian in question and a pair of unrelated mugging videos, makes a series of inaccurate statements.

A favela is not a crime-ridden slum, as many favelas have little crime at all, and a cursory Google Maps search would have shown the author that many of Rio’s most well-known favelas are concentrated in the heart of the city. “Favela” is not synonymous with gang presence, and as to the question of favelas being “long dominated” by gangs, Rio’s principal organized crime groups only began consolidating control of favelas in the 1980s. The first official favela, in comparison, was settled in 1897 and there are others that predate even that.

Travel pieces tend to veer into similarly safari-sounding language, as is the case with this travel piece for The Telegraph on the top cruise-accessible cultural destinations in South America. In three sentences, the blurb on favelas manages to do nearly everything wrong: “Favelas are the slums, or shantytowns, of Brazil. Not immediately the most alluring excursion destination, but the millions who live in the shacks call them home. Rio’s hundreds of favelas have produced renowned samba and artistic talent and many tourist visits are conducted by guides from these communities.”

Leaving aside the fact that this blurb misses an opportunity to connect readers to resident-led tours—the paragraph mentions a cruise company-operated “educational” favela tour to Rocinha and links to a £2500 cruise to Buenos Aires—one has to wonder why the author would juxtapose this sort of home-shaming (“the shacks”? Has he been to Rio?) with a lackluster pitch for wealthy travelers.