For the original article in Portuguese by Bruno Villas Bôas published by Valor Econômico click here.

Residents of Brazilian favelas have a combined purchasing power of R$119.8 billion (US$27.7 billion) per year, an amount that surpasses the income of 20 of 27 Brazilian states. This value surpasses that of entire countries, including Paraguay, Uruguay, and Bolivia. There are 13.6 million people in favelas, with a per capita average monthly income of R$734.10 (US$170).

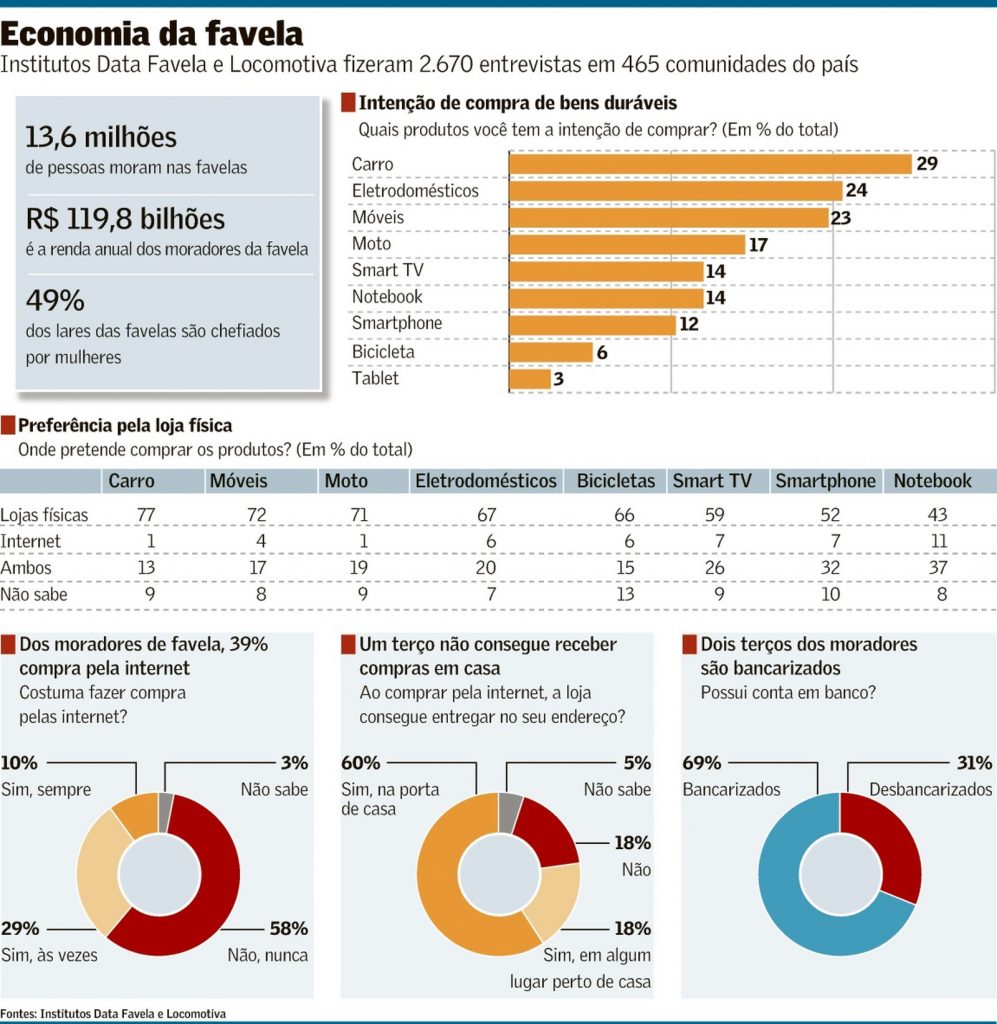

These indicators are part of the “Economia das Favelas” study (“Favela Economy”), undertaken by the Data Favela Institute and Locomotiva Institute. The two conducted field research from December 8 to 16, 2019 in 465 favelas in 116 cities. In total, they interviewed 2,670 people age 16 or over who self-declared as favela residents.

The survey shows that most favela income comes from work. Of residents with an income, 71% said their income came from work (formal or informal). Of all residents, 40% received unemployment benefits, and 24% received payments from the Bolsa Familia federal cash transfer program. Just 15% lived on a retirement or pension plan.

Renato Meirelles, president of the Locomotiva Institute, says that the study reveals that favelas make up a large consumer market with a universe of people with purchasing power, who are connected to the Internet and possess bank accounts. For him, it is a market that is still underestimated by large companies.

“We see large companies expanding to cities with 7,000 inhabitants before they head to favelas, who have more consumers,” says Meirelles, considered one of the principal specialists in consumption and public opinion in the country. “To understand the favelas as territory open for consumption can be a shortcut for Brazilian companies to expand.”

The survey details the profile of consumption in favelas, including the use of new technologies. Six of ten residents said they had used the Internet to solicit transportation services (with Uber, 99, and Cabify) in the 30 days prior to the study. More than 43% used a cell phone to consume paid content on websites and 33% to order food for delivery.

Durable goods, on the other hand, top the list of desires for favela residents. The study shows that 29% of those interviewed intend to buy a car in the next 12 months. Also listed were domestic appliances (24%), furniture (23%), motorcycles (17%), smart TVs (14%), laptops (14%), and smartphones (12%), for example.

Born and raised in Rocinha, the largest favela in Rio, Fabiana Rodrigues says that acquiring a car this year is a possibility. Her husband has a motorcycle, but is now working on getting his driver’s license. The challenge is finding parking in the favela. The roads are packed with parked cars.

“People have an incorrect image of favelas and are surprised when they enter Rocinha. People have everything here: televisions, cars, motorcycles, brick houses. They are people with income, who work in the South Zone of Rio,” says Fabiana, who is currently dedicating herself to the task of monetizing her social media accounts.

Married and with two children, Fabiana is an influencer in Rocinha. Her Facebook page, called Rocinha em Foco (Rocinha in Focus), has around 110,000 followers. Her Instagram has 21,100 followers. She publishes news about the neighborhood and promotes commerce and services inside and outside of the favela, such as digital banking services.

Tati Damasceno, 28 years old, also dreams of buying goods. A resident of Vidigal, Rocinha’s neighbor in Rio’s South Zone, Damasceno graduated with a degree in nutrition and opened her own restaurant with her father, who is a cook. With her income, she hopes to buy a motorcycle this year.

“In our restaurant, we deliver by foot to various points in the neighborhood, which is very large. Buying a motorcycle would facilitate delivery,” says Damasceno, who has an income of R$1,000 to R$1,500 per month (US$230 to US$347) with the restaurant.

The favelas are full of small businesses like beauty salons, clothing, footwear and toy stores, small grocery stores, pharmacies, and restaurants. For major retail brands, however, there are different barriers to entry in the favelas. The most noted of these is the lack of security, a reflection of the presence of drug trafficking gangs and militias.

In Rocinha, for example, some brands have come closer in recent years. The Brazilian fast-food chain Bob’s opened a restaurant in the favela even before pacification in 2013, and with the installation of Pacifying Police Units (UPPs), the favela gained Cacau Show and Subway franchises. Since the onset of worsening violence and the national economic crisis, only Subway remains.

Beyond security, logistical factors provide additional challenges for companies. Parts of the favelas are made of up narrow streets and alleys without zip codes, making delivery services impossible. According to the study by Data Favela and Locomotiva, 33% of favela residents purchase online. Of those that buy, however, almost a third are unable to receive products at their house. According to Meirelles, residents end up indicating a place close to home (like the resident’s association or post office) to receive products, or a relative’s house. “Many online sales have been lost because of these kinds of limitations,” says Meirelles. “But there are incentives to confront the problem.”

To fill these gaps and take advantage of the consumption potential in favelas, companies come looking for local partners. That was how Favela Log came about, for example. A product distributor that specializes in favelas, the majority of their delivery persons are favela residents and some are former inmates.

According to Celso Athayde, president of Favela Holding, which controls the logistics company, their first client was Procter & Gamble Brazil. Next, the company began to distribute TIM sim cards in favelas. Later, it aided in the sale of scratch cards. Today, one of their clients is the cosmetics company, Natura.

“Some of Natura’s direct sales consultants live in favelas but were unable to receive products at home to resell to customers. They had to schedule to meet in places outside of the favela to receive the products, like at gas stations,” says Athayde.

Founded in 2015, Favela Holding is a business arm of Central Única das Favelas (CUFA), a social organization founded by Athayde and rapper MV Bill. This group includes Data Favela, one of the groups responsible for this research in the favelas, as well as dozens of other service companies distributed among Brazilian favelas.

Offering access to the purchasing power of favelas became a business for the administrator Leonardo Ribeiro, 41 years old, as well. In 2016, he created Comunidade Door, a company that has now installed 10,000 two-by-one-meter billboard announcements on the walls of favela houses. The company has already hosted campaigns from Uber, Coca-Cola, Del Valle, and Claro.

Ribeiro says he billed, for 2018 and 2019 together, R$20 million (US$4.63 million) with his business and generated income for approximately 15,000 favela residents. “We have mapped the residents of favelas to offer brands campaigns segmented by income, age group, and gender,” explains the businessman, who founded the company in 2016.

The difficulty in accessing favela consumers is not limited, however, to the physical territory. The favela public does not identify with major brands, says Locomotiva’s Meirelles. For him, one of the reasons behind this phenomenon is that company executives have culturally and socially distanced themselves from favela residents and the lower-income public.

According to the survey, just over 70% of favela residents interviewed consider themselves to be very reliable, honest, happy, and concerned with the wellbeing of others, for example. When asked to rate brands in these same aspects, less than 50% attribute the same qualities. For example, only 28% considered companies to be “very honest.”

On the other hand, favela residents attribute themselves less frequently with the perception of being very innovative, intelligent, or rich. These are characteristics frequently attributed to brands. “The favela likes samba, rap, and funk. Executives don’t understand that. So, there is still a huge cultural distance for favelas,” sums up Favela Holding’s Athayde.