The 16 favelas that make up Complexo da Maré, in Rio de Janeiro’s North Zone, registered 49 deaths resulting from armed violence in 2019, more than double the rate of 2018. Of these deaths, 34 occurred at the hands of police and 15 from armed civil groups. Throughout 2019, the group of favelas saw 117 days of shootouts and nearly 300 total hours of police operations. These and other indicators of rising violence in Maré are compiled in the 2019 Right to Public Security in Maré Bulletin, an annual report produced by the NGO Redes da Maré (Maré Development Networks) and launched on February 14.

The bulletin’s publication comes as Rio police have engaged in a series of violent operations in Maré over the last several weeks, with police incursions taking place January 29, February 12, and February 18, the third lasting over 15 hours.

The bulletin’s publication comes as Rio police have engaged in a series of violent operations in Maré over the last several weeks, with police incursions taking place January 29, February 12, and February 18, the third lasting over 15 hours.

For Aline Maia, coordinator of the Right to Life and Public Security Program at the Observatório de Favelas, the bulletin goes a long way in explaining the effects of these numbers. “This isn’t just a statistical work,” said Maia, speaking at the launch event. “There are some data points that are difficult to quantify, that, even so, this bulletin manages to portray with real clarity.”

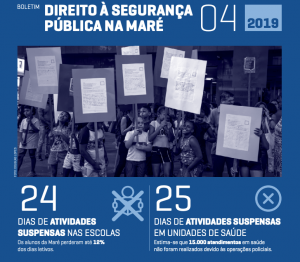

In the area of education, for example, Maré schools suffered 24 days of closures due to police operations in 2019—12% of the school year. “And if we want a progression of this accumulation, from 2016 to now, we see that there were 89 days without class [over those four years],” said Maia. She continues: “This has a direct effect, especially when it’s time for us [from the favelas] to compete for entrance to public universities [the best in Brazil]. We’re talking here about the right to education, which is being denied to 16,000 children.” Health posts, meanwhile, were forced to close their doors on 25 separate days.

Maia also pointed to the profile of the victims of police violence in Maré: 100% of whom were black or brown. “In these confrontations, not a single white youth died,” emphasized Maia, “this is really indicative of the racial cleavages that Brazil is living through today.” Of the total 49 killed by police as well as armed civil groups, 96% were black or brown, 94% were male, and 85% were between the 15 and 29 years old.

The Case of Vitor Santiago and State Impunity

Vitor Santiago Borges was 29 when he was shot twice by a member of the armed forces in Maré. The two bullet wounds left him paraplegic with an amputated leg. “The report shows who the victims are: black, young, male favela residents,” said Borges, agreeing with Maia. Borges was driving back from watching a soccer game with a group of friends in 2015 when a soldier (stationed in Maré as part of the armed forces’ occupation of the favelas in 2014-2015) opened fire on their car, alleging the group had sped through a checkpoint. Speaking for the first time in public after a long hiatus, Borges lamented that those shot and killed by State agents were unable to tell their own stories.

“The words ‘intelligence’ and ‘public security’ don’t fit in the same sentence,” said Borges, adding that the State neglects to ask the simple question of why and how youth become involved in drug trafficking.

The final hearing for the soldier that shot Borges took place on the afternoon of February 18, resulting in a unanimous ruling to absolve the soldier of all wrongdoing. The Military Public Prosecutor (MPM) cited “putative legitimate defense,” a legal tenet that allows for exculpation on account of imagined danger. The soldier in question, said prosecutors, though in no imminent danger, thought Borges’ car posed a threat.

“This is military corporatism,” said Irone Santiago, Borges’ mother, following the ruling. “This should have been judged in a common trial.” A 2017 law signed by former President Michel Temer transferred cases involving armed forces members that kill in the line of duty from civilian courts to military tribunals. “It’s military judging military, right? We know more or less what’s going to happen,” Borges had said prior. “I think that from now on, this sort of thing will only get worse,” he said later, worried over the legal precedent.

The Right to Security bulletin offered similarly grim evidence of impunity. Over the entire year, Rio Civil Police conducted crime scene analysis following police operations in Maré only three times. In all three cases, forensics teams arrived only after the Redes team contacted them directly.

The ‘State-ization’ of Homicides

Speakers at the bulletin’s launch did not shy away from the fact that 2019, under newly-elected Governor Wilson Witzel, brought unprecedented levels of State-sponsored violence across Rio. Urged on by violent rhetoric (“the order is to shoot to kill,” Witzel has said) Rio police killed a record 1810 people in 2019, an average of five people per day.

Pedro Abramovay, Open Society Foundations director for Latin America and the Caribbean, noted the importance of not treating 2019 as separate from a longstanding trend. Questions of authoritarianism, misogyny, and racism, said Abramovay, were also solidified during progressive governments. 2019, instead, has created openings for these trends to further entrench themselves.

“What is happening now is a radicalization of a process that already existed, but at a level that we have never seen before,” said Abramovay. The current scenario has also led to what Abramovay called the ‘state-ization’ of homicides, resulting from the combination of the government’s “clear connection” to militia groups and increased levels of police killings as a proportion of total lethality. That is: the homicide rate in Rio has fallen, but “deaths at the hands of the police increased so much, that the rate of violent death is practically stable in Rio de Janeiro.”

A Tool for Change

Faced with these challenges, the bulletin serves as a tool for change. “The aim of this bulletin is to show evidence of the violence happening in Maré, so its residents can reveal and deconstruct current government policies,” explained Camila Barros, coordinator of the Eyes on Maré project leading the bulletin’s production at Redes. “It is a tool for disputing these policies.”

Event participants agreed that by distributing the report, they might engage the rest of Rio, making violence in the favelas a common concern. After all, “the favela is part of the city,” said Maia.