This is our latest article on the new coronavirus as it impacts Rio de Janeiro’s favelas.

“That’s what’s happening. If you don’t create a plan for the peripheries of the whole country, you choose to let the poor die by their own luck.” — Gilson Rodrigues

As confirmed cases of Covid-19 appear in favelas across Brazil, residents are demanding immediate and specific measures to ensure their right to isolate amid oncoming economic paralysis. Despite President Jair Bolsonaro’s minimization of the crisis (he has referred to Covid-19 as a “little flu” and blamed both the media and state governors for creating “hysteria”), public health professionals are unequivocal on the effectiveness and need for social isolation.

Closer adherence to social isolation measures means a slower infection rate, ensuring the sickness does not overwhelm health care system capacities, a result that has become known globally as “flattening the curve.” Favela residents, however, both on account of neighborhood density and economic informality, are often unable to exercise their right to isolate and protect their communities.

Social Isolation Remains Unaffordable for Many Favela Residents

From Rio de Janeiro Governor Wilson Witzel’s first recommendations to stay at home, favela activists and residents alike began to raise their voices, pointing out the crucial concern: many workers do not have the luxury of working from home. “The solutions presented for many do not fit all,” read a Facebook post from longtime community leader Itamar Silva, from Santa Marta, a favela located in Rio’s South Zone.

Indeed, these measures are a class privilege, protecting only the portion of the population that can afford to implement them: remote work is not a viable option for those who do not have access to a computer or Internet, not to mention that most favela residents work in operational jobs that can only be performed in person. In a public letter, the #CoronaNasPeriferias coalition, a group of communicators from Brazilian peripheries and favelas, asserted that: “[Isolation] is not allowed in our reality! The periphery is the domestic employee, the doorman, the app driver, the delivery man, the informal worker who needs to be in the bus and in the subway selling his products to bring income to the house, or the local merchant who cannot suspend his activities.”

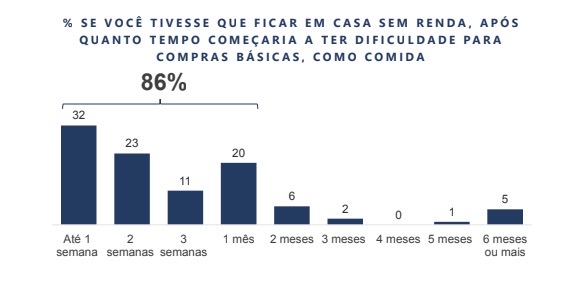

These workers find themselves in a dilemma: continue to work or stop eating. This is especially the case for favela residents, 86% of whom declared they would have difficulty buying food within one month if they had to stay at home without income, according to a survey conducted by the Data Favela polling group. For mothers in the favelas, the figure rises to 92%.

Experiences from other countries show that quarantine may last far longer. Wuhan, China, the heart of the epidemic outbreak, is about to lift lockdown after more than two months; Italy, the country with the highest Covid-19 death rate, has spent four weeks with strong social isolation measures with no clear end in sight; and many Latin American countries are already imposing strict, renewable lockdown measures for several weeks at a time.

Selective Quarantine: Favela Residents Most Exposed

Many unprotected workers, therefore, continue to work out of necessity, leaving home and exposing themselves to the virus. Rio de Janeiro’s initial containment measures did not prevent the virus from entering the favelas. These communities, often dense, now face an uphill battle, as local conditions provide a dangerous breeding ground for the virus’s propagation, made worse by unreliable access to water and a lack of basic sanitation.

Workers from outlying areas continue to cross the city, running the risk of infection on public transportation and in the areas they service, often the city’s wealthier areas. “The first cases in Rio occurred in people who were circulating abroad, which are usually the people with more purchasing power. Now, there are people working in their homes, in the South Zone and in Barra. Babysitters, maids, day laborers, drivers who come from poorer regions and who will take the virus to their homes,” warned the infectious diseases specialist Edimilson Migowski in an interview with G1 Globo.

In the first days of the epidemic, one emblematic case spoke to this reality: a Rio de Janeiro maid died after possibly contracting Covid-19 from her boss. Her employer had self-quarantined in her upscale Leblon apartment after returning from a trip to Italy without warning or exempting her maid. Similarly, one of São Paulo’s first suspected coronavirus deaths was a 25-year old Uber driver.

As schools closed across the state, many favela parents have had little choice but to leave their children in the care of their grandparents, most of whom fall directly into the disease’s designated at-risk group. This is even more frequent in the 20% of favela households led by single mothers.

Atop Risk of Infection, Steep Drop in Income for Informal Workers

As social isolation measures are strengthened, many foresee a blow to household finances. This is the case for 84% of favela residents, who expect their income to suffer during the crisis. Favelas are particularly vulnerable to the city’s paralysis, as the majority of favela residents work in the informal economy. The Data Favela survey shows that 68.75% of favela workers are considered informal (self-employed, freelance, or without any type of contract with their employer) compared to 41.3% nationally, according to the most recent assessment by the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE).

Empty beaches, squares, and buses have left street vendors and informal salespeople (camelôs) without customers. Employers are no longer calling in search of day labor. Many are now left in a precarious situation. “As alarming as this sounds, it may indicate a situation of social upheaval in the near future,” affirmed Renato Meirelles, founder of Instituto Locomotiva, which produces Data Favela, in the study.

Avoiding Double Jeopardy: Favelas Search for Immediate Solutions

Favela activists have pointed to the need for economically viable containment measures and many have mobilized to implement local emergency solutions to meet the needs of their communities. This was the case of a group of youth from the peripheries who are the children of domestic workers that penned a manifesto for “liberation with remuneration for our mother’s lives” (essentially, temporary paid leave). The group pointed out that their mothers faced the impossible choice of either continuing to work as domestic servants for wealthy families in the city’s South Zone or take off and lose their pay.

Brazil has more than 6 million domestic workers, the majority of whom are non-contractual and therefore unprotected, making them dependent on the altruism and generosity of private employers, a remnant of Brazil’s inequality rooted in its history as the world’s largest slave state. Many activists are calling for solidarity. As William Reis, coordinator of the socio-cultural project AfroReaggae, wrote in Veja Rio: “It is time for the union of the State. It is time for those who have the privilege of having a maid at home to put into practice the rhetoric that ‘she is almost family’ and take care that these women who take care of their children do not have their health affected.”

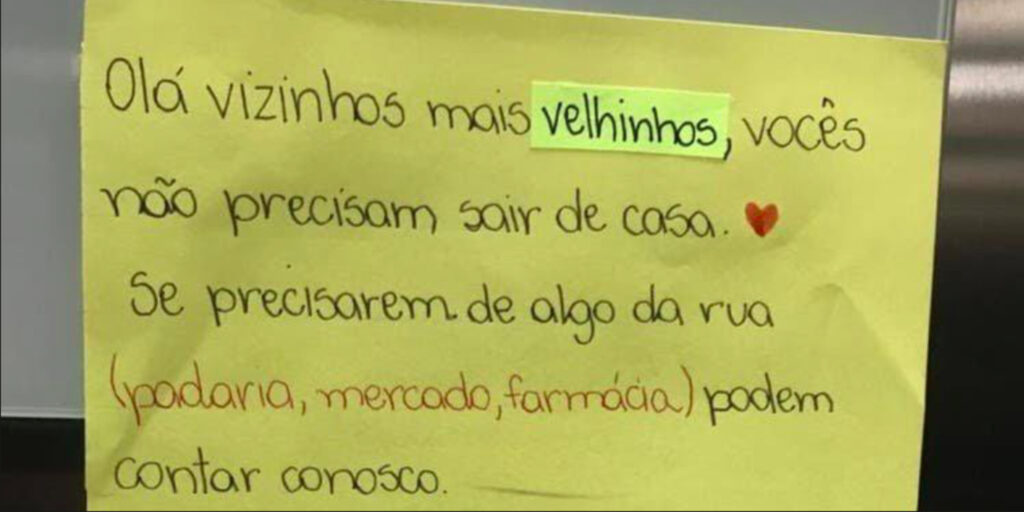

Local organizations have also sent out calls for donations in money, hygiene products, and foodstuffs to respond to the urgent needs of their communities. They started distributions immediately. Residents also activated local solidarity networks to support one another within their communities, with efforts to shop for the elderly, share running water, and circulate health and prevention information.

Citizen Mobilization for Policy Responses

The scale of the crisis, however, requires structural measures, and many citizen networks have united to call for policies targeted at the most precarious workers. On March 20, just days after social isolation measures were taken up in several Brazilian states, including Rio de Janeiro, a group of more than one hundred civil society organizations launched a campaign to demand an emergency basic income of up to R$1500 (US$287) per family for informal workers, and thus for the vast majority of favela residents. In just four days, over 430,000 signatories joined the movement. When Paulo Guedes, Brazil’s hyper-orthodox Minister of Economics, announced a R$200 (US$38) payment for only 38 million workers, economists and favela thought-leaders erupted. Among these were Nathália Rodrigues, the YouTuber and low-income financial educator commonly known as Nath Finanças, who tweeted, “It’s VERY LOW. It doesn’t even pay the rent.”

The mobilization bore fruit. The government buckled under pressure and approved R$600 (US$115) for individuals or R$1200 [US$230] per family (or this same amount in the case of single mothers), and Congress passed the measure days later. It will apply to some 100 million unassisted informal and low-income workers as well as unemployed over a period of three months. The government has now launched the program’s registration website and app, and payments are expected to begin this week.

Though the basic emergency income represents a major victory, the measure is not unlike efforts being adopted elsewhere, as governments launch unprecedented stimulus packages to mitigate the economic impacts of the pandemic and speed recovery. In the US, the Trump administration approved $250 billion in direct payments with values starting at US$1200 to low and middle-income individuals and families; Chile, Argentina, Canada, India, Peru, Portugal, and many others are also creating cash transfer programs for those who have lost their income.

Presidential Missteps and Interference

Aside from taking last-minute ownership and credit for basic income payments, President Bolsonaro’s actions have either misfired or, worse, have directly obstructed attempts to protect vulnerable populations.

Bolsonaro issued an executive decree that included an article allowing companies to suspend employee salaries without firing them for a period of up to four months. The measure received immediate backlash from opposition parties and civil society, and the article was withdrawn from the decree within hours.

While governors from around Brazil have acted quickly, some with proposals to postpone utility payments and many acting in support of basic income measures, those who opted to close down non-essential services and limit circulation have seen their efforts contravened by the federal government in both uncoordinated policy and anti-science rhetoric.

Following a televised address in which the president questioned containment measures, favelas reported renewed circulation. The government even attempted to launch an anti-social isolation communication campaign titled “Brazil Cannot Stop,” featuring video content advocating for commerce to reopen, and depicting and targeting mostly the black, informal, and lower-income segments of the population. Widespread outcry and judicial action from the Supreme Court had the campaign pulled; the government has since retooled it under the name “No One Left Behind.”

For many activists, this amounts to mass extermination. “That’s what’s happening. If you don’t create a plan for the peripheries of the whole country, you choose to let the poor die by their own luck,” said Gilson Rodrigues, a community leader in Paraisópolis, São Paulo in an interview for BBC News Brasil.

Protecting the Essential, the Vulnerable

While solutions are to be taken to ensure that the majority of the population stay at home, many others will have to continue to cross the city, walk the streets, interact with hundreds of people every day, and work to guarantee the quarantine of the rest of the population. They are the employees of essential services, cashiers of supermarkets, garbage collectors, doormen, security guards, delivery workers, day laborers, and pharmacists. For Gizele Martins, a community journalist from the favelas of Maré, we must remember these people, today and at the end of the crisis. In an article for Brasil de Fato, she wrote: “Now look at the city, see that without the favela it doesn’t work, because we are the ones who make the economy work with our labor. Without us there is no city. So, please governors and society, include us in public policies, in basic services, in bills, in information, in basic sanitation.”

The Covid-19 crisis has rendered this shadow army of workers more visible than ever. As hunger begins to set in, the federal government is running out of time to implement physical protection and financial support for the nation’s most vulnerable populations and most crucial workers.