This is our latest article on the new coronavirus as it impacts Rio de Janeiro’s favelas.

For a full two weeks, the global Covid-19 pandemic seemed enough to curb police violence in the favelas of Rio de Janeiro. Now, they say, the violence is back, and it’s getting in the way of community coronavirus mitigation campaigns. As state police scrambled to adapt to isolation measures decreed by Governor Wilson Witzel in mid-March, favela human rights activists took advantage of the momentary ceasefire, concentrating their efforts on coronavirus mitigation. April’s return to violence now threatens their work.

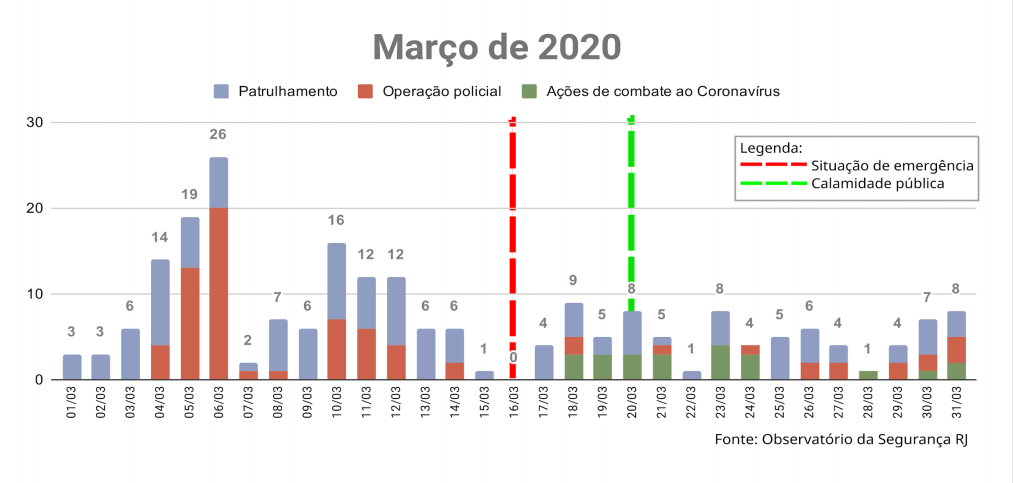

According to a new report by the Network of Security Observatories (ROS), a monitoring body, March 2020 saw a 23% decrease in “police operations”—violent incursions into favelas, ostensibly undertaken to combat Rio’s illicit drug trade—in comparison to March 2019. After March 16, the total number of operations dropped 74% in comparison to the first half of the month.

“Police forces were trying to figure out how to react, how to undertake their ordinary activities in this new context,” said Pablo Nunes, a social scientist and security analyst at the ROS. Alongside a drop in police operations, said Nunes, the ROS noted increased activity in relation to containment measures, including highway checkpoints and isolation control, translating to a drop in the number of people killed during police operations in March: 15 compared to 26 for March 2019.

“There was, in fact, this change,” said Cecilia Oliveira, director of the Fogo Cruzado platform and specialist in public security. “The governor redirected many police to actions related to coronavirus.” According to the ROS report, Rio police gave “repress drug trafficking” as motivation for operations 43% less in March of 2020 compared to March 2019.

April 1: Business as usual

The peace was short-lived. The first week of April, cautioned Nunes, had already brought a return to the status quo, with police operations returning to their regular frequency. He attributed the change to mixed messaging from the federal government: WHO-friendly orientations by Health Minister Luiz Henrique Mandetta and anti-containment rhetoric by President Jair Bolsonaro had left Brazilians torn over how to behave. “So we’ve seen not only an increase in the number of people in the streets, but we are also seeing that police operations are going back to normal.”

On April 3, a police operation in the favela of Acari, in Rio’s North Zone, left three dead. “Until last week, things were looking positive: operations weren’t happening and the streets were really empty,” said Buba Aguiar, a resident, sociologist and activist at the collective Fala Akari, on April 7. Now, she said, “the operations are happening with much greater frequency, with the use of caveirões [armored personnel carriers] and gunfire. At the same time, the streets have gotten more crowded. So we have two worries: the same one as always, which is the risk of someone getting shot or killed, and the spread of the virus.”

On April 6, a police operation conducted in the favelas of Maré, near Rio’s international airport, lasted over eight hours. “Operations have lasted for hours, with houses being torn apart, robberies, killings, in a moment like this, of pandemic, of crisis,” said Gizele Martins, a Maré resident and favela communicator.

Martins, whose work usually addresses human rights and police violence, is part of the Maré Mobilization Front, a collaboration between local collectives dedicated to raising awareness of coronavirus prevention methods.“We live in a society, where we have to survive this [police violence] every day,” said Martins. “Now imagine what it is to survive this in a massive health crisis, at a moment when we are also scared of this virus.” Maré registered its first confirmed Covid-19 death on April 8.

Operação policial acontece no Parque União e Nova Holanda desde às 5h dessa segunda-feira. Moradores relataram a presença do caveirão da PMERJ circulando as ruas.#DeOlhonaMaré #OperaçãonaMaré pic.twitter.com/wY99LCS1Te

— Redes da Maré (@redesdamare) April 6, 2020

#ALERT #PublicSecurity

Police operation in Parque União and Nova Holanda favelas ongoing since 5 AM this Monday. Residents report military police caveirão presence in streets. #EyesOnMaré #OperationinMaré

“It’s likely that the families waiting for food baskets on Monday, to have something to eat at home, went another day without eating.”

After weeks of successfully distributing foodstuffs, cleaning products, and informational materials, organizers said recent police operations had begun to impede their efforts. Popular communicator Juliana Pinho, also a member of the Maré Mobilization Front, said April 6’s police operation had cost them a day of work. “All of our mobilization and awareness-raising actions, our help to residents, were interrupted. Organizations’ distribution of basic food baskets to residents, which has happened every day, was suspended,” said Pinho. “It’s likely that the families waiting for food baskets on Monday, to have something to eat at home, went another day without eating.”

Referring to police operations in Acari, Aguiar said she too was held up. “Yesterday, I couldn’t leave the house; I was trying to leave just as they were starting the second operation of the day. So I was unable to withdraw an important bank transfer to guarantee residents [impacted by coronavirus] basic food staples.”

“We’re talking about people in positions of extreme vulnerability,” added Pinho. “And they had their rights—which are guaranteed by organizations and collectives and not by the State—and even so, they had their rights violated.”

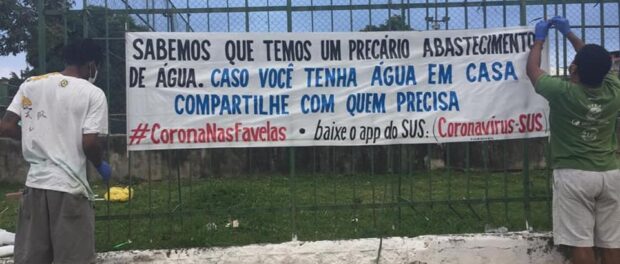

“The State continues to offer police and genocide for this population,” said Martins. “The population of the favelas and the peripheries works to eat. In a moment like this, how are they supposed to stay at home if they work to eat? So it is an obligation of the authorities to consider basic income measures, to consider the distribution of cooking gas, of clothes, of food, hand sanitizer, cleaning products, water.”