This is our latest article on Covid-19 and its impacts on favelas and in the series of Teach-Ins on Covid-19 in favelas.

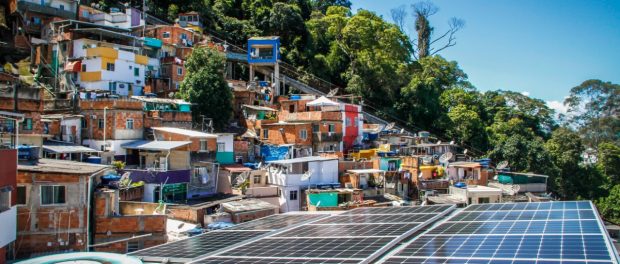

On June 10, the Sustainable Favela Network’s (SFN)* Solar Energy Working Group held an online teach-in “Is Solar Energy in Favelas Possible?” Nine participants shared their experiences with an online audience of more than 100 people on Zoom, debating everything from technical information for installing solar panels in favelas to direct benefits for residents.

The roundtable discussion featured: Natália Chaves, environmental scientist and member of the Rede Brasileira de Mulheres na Energia Solar (MESoL, the Brazilian Network of Women in Solar Energy); Hans Rauschmayer, specialist in solar energy from Solarize; Otávio Alves Barros, president of the Residents’ Association of Vale Encantado, in Alto da Boa Vista; Adalberto Almeida, cofounder of RevoluSolar in the communities of Morro da Babilônia and Chapéu Mangueira, in Rio’s South Zone; Eduardo Avila, executive director of RevoluSolar; Henrique Drumond, cofounder and CEO of Insolar; Verônica Moura, Insolar ambassador in Santa Marta, in the South Zone; Elma Maria da Silva de Alleluia, president of the NGO SER Alzira de Aleluia, in Vidigal, also in the South Zone; and Alessandra Biá, who leads the Escola Libertária de Artes (ELA, the Liberatory School of Arts) in a traveling minibus that uses a solar panel to generate power, circulating through Complexo da Maré, in the North Zone.

The speakers had the opportunity to exchange experiences and discuss the main challenges for the adoption of solar energy in Rio’s favelas. They revealed how their initiatives already provide practical examples of successes and how sustainable strategies can be combined and expanded to other communities.

Chaves mediated the conversation and began her presentation highlighting the importance of energy derived from less environmentally harmful sources, like solar. She added that, to achieve this transition to cleaner energy, “we must include social responsibility and diversity when we talk about sustainability.” Chaves pointed to the United Nations‘ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) as guidance for the fulfillment of three important goals: access to affordable and clean energy (SDG #7); inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable cities (SDG #11); and the fight against climate change (SDG #13).

Possible Experiences

Rauschmayer, a pioneer in the promotion of solar energy in the city of Rio de Janeiro, emphasized the importance of the Sustainable Favela Network’s Solar Energy Working Group, which brings together different experiences, reaping benefits from local to federal levels. He explained the technical aspects of constructing solar infrastructure and how these are handled in the processes and partnerships of his business, Solarize, whose main objective is to train specialized workforces. Rauschmayer pointed to an increase in this sector in Brazil, noting that “we have more than 300,000 solar installations since 2013, creating more than 100,000 jobs, and we still have more potential.” He cited the example of the Galpão Bela Maré exhibition space, in Complexo da Maré, which, after installing panels, has begun saving an approximate R$20,000 (US$3,739) per year.

On the subject of democratizing solar energy in the favelas, Henrique Drumond from Insolar addressed how social businesses can focus on inclusion and facilitating access to this service in conjunction with the provision of environmental benefits. “When you let someone generate their own energy, they can save on their energy bill and invest in the wellbeing of their family, in better food, education, etc.” He finished off explaining how the partnerships are collaborative: “we talk with local leaders, we look to bring the training so that the residents themselves can carry out the installation, giving the maximum opportunity for them to set up their own business and take the technology and the knowledge for themselves.”

Drumond cited Santa Marta to exemplify how collaboration can grow and generate scalability. “We started with a pilot project in Santa Marta at the Creche Mundo Infantil daycare center,” said Drumond. “The second phase is local expansion in partnership with residents, including funding and donations. The last stage is democratization, when it gets to the families.” Moura, an ambassador for Insolar in Santa Marta, emphasized that community leadership is important: “The residents did the research and the people decided which institutions would participate in the pilot project. We thought about it and built it together; the community is an important part of that renovation. We believe that other favelas can also have access to solar energy.”

See featured slides here:

Challenges & Opportunities

Almeida, cofounder of RevoluSolar, resident of Babilônia, and one of the first to install solar panels in Rio’s favelas, reported some of the problems that residents of favelas face, mainly in terms of neglect from the private electric utility Light. “When there is a blackout and we call Light, they take hours and even days to show up. That’s when residents opt to informally siphon off the power supply, running a great risk of fires and burning out domestic appliances.” He also pointed out the high prices paid by families in these communities and the difference in the services provided to residents of favelas compared to other neighborhoods in the city. Almeida asked why: “We have to wait for hours and days without a response from the energy utility that we pay. Do we only have the right to vote but don’t have consumer rights just because we are favela residents?”

Avila, also from RevoluSolar, explained that the charges on electric energy in favelas are high because they are based on estimates and not on real consumption. “It isn’t just dissatisfaction with the quality of the service and with the price, but there is this feeling of injustice and powerlessness, which is very strong.” Within this panorama, the organization aims to train residents as well as offer awareness-raising workshops for children, events, and research projects. It was through one of these research projects that the group found that Rio’s hillside favelas enjoy a privileged position for capturing and generating solar energy.

Today, the group works in the favelas of Babilônia and Chapéu Mangueira and is already preparing for a new initiative: the first solar energy cooperative in Brazil’s favelas. “We adopted shared generation, which is in harmony with the sense of cooperation and community in favelas. We already have equipment that partners are going to donate, but we are missing some supporters in order to take the next steps in this project.” Avila invited potential partners to look for information and collaborate.

The president of the Residents’ Association of Vale Encantado, Alves shared an experience from his community and emphasized how actions for saving energy can be developed little by little. “One of the initiatives is to start to save with a low-cost solar water heater [see image below]. It makes such a difference for your wallet, but people have no idea. If you are organized, you can save R$120 (US$22) per month on a R$300 (US$55) bill.” For many people who still see solar energy as something expensive and elitist, Alves clarified that residents can start with materials that they have at home if they have the support of specialist groups.

New Horizons

In a minibus equipped with a solar panel, the ELA Liberatory School of Arts travels around Complexo da Maré, transporting not just culture and education, but also opening horizons and new possibilities for residents. Alessandra Biá, the force behind the initiative, said: “I’m still delighted with this methodology and with solar energy coming together with the communities.” She added, on the topic of interaction with residents: “The moto-taxi drivers are fascinated, and everyone dreams together. Everybody wants to be an electrician. They want to do courses and learn to use [solar energy], and the kids also want to understand how that works, and that’s really great,” she concluded.

Silva says that the SFN Solar Energy Working Group was her way into being able to understand and take solar energy to the NGO Ser Alzira de Aleluia in Vidigal. “With solar energy, people can leave behind the practice of siphoning energy off the grid, and trying to hide their consumption, reducing informality. Unity between communities is also very important. We need platforms to increase knowledge and understanding so that everyone can see that it is possible and viable.” Silva thinks this is a moment of urgency and that the current pandemic can be a catalyst for the desire for change in favelas.

Silva says that the SFN Solar Energy Working Group was her way into being able to understand and take solar energy to the NGO Ser Alzira de Aleluia in Vidigal. “With solar energy, people can leave behind the practice of siphoning energy off the grid, and trying to hide their consumption, reducing informality. Unity between communities is also very important. We need platforms to increase knowledge and understanding so that everyone can see that it is possible and viable.” Silva thinks this is a moment of urgency and that the current pandemic can be a catalyst for the desire for change in favelas.

Questions from the Audience

The online teach-in then opened up to audience members’ questions about the use of solar energy. On the topic of the main bottlenecks for installing solar energy in favelas, Almeida and Avila agreed about the difficulty of financing. The latter pointed to, “the lack of an institution that is able to make this investment and partnerships to design a way for residents to be able to pay monthly. It’s a question of allocation [of resources] because it is difficult to invest everything at the beginning.” Almeida described how many financial institutions refuse to give a line of credit to those living in favelas.

Chaves, the event’s moderator, recalled the essential point of community engagement and the need to “look at the reality of the place, so that, yes from there, we can contribute to the initiative.” Moura identified the challenges in Santa Marta. “We are talking with [other] residents. The communication process needs to show the long-term benefits. This is our greatest difficulty in the community. It is easier with young people and many residents have questions. Will this get me into debt? Am I going to see the benefits? I think that communication and education are fundamental for favela residents, especially for older people.”

Drumond observed the importance of finding diverse solutions. “You need to study the available spaces. Some communities have more space available, others less. I think that the solutions complement each other: if you generate energy on the roofs that are in a condition to receive it, improve the roofs which aren’t ready, or generate energy in greater quantities to distribute, we have various options available.”

Offering an example of a successful initiative that combined different environmental actions, including solar energy, Drumond spoke of a case in Santa Marta. “On top of the samba school and on the residents’ association, we have many panels. We cleared the charges of the headquarters of the association with twelve panels, in a space that also houses a music and dance school. We made roofing with bioconstruction. Because of the accumulation of water from the roof, we built a gutter that collects rainwater and waters a green wall. The whole building embraced sustainability,” Drumond celebrated.

Watch the Teach-in here:

*RioOnWatch and the Sustainable Favela Network are initiatives of Catalytic Communities