“There is no more pleasure over there on the Hill of Pleasures [Morro dos Prazeres]…” This line, from the composition by the songwriter and poet Paulo César Pinheiro, comes from the song ‘Nomes de Favela [names of the favelas]’, a typical samba sung with a mouth full of life and eyes full of tears.

“There is no more pleasure over there on the Hill of Pleasures [Morro dos Prazeres]…” This line, from the composition by the songwriter and poet Paulo César Pinheiro, comes from the song ‘Nomes de Favela [names of the favelas]’, a typical samba sung with a mouth full of life and eyes full of tears.

Pinheiro’s song harks back to a time when making samba in Brazil was associated with being different. Today, people generally consider funk carioca, or just funk [a dance music style popular in favelas that developed from Miami Bass], and its practitioners to be in that position, regardless of the lyrical composition of its songs. “The repression is less focused on funk as music and more on the funkeiros who make it, who are mostly black favela residents. Funk plays in places popular with middle class audiences, but the real question relates to the bailes funk [the funk parties held in favela communities]. It is no coincidence that funk is being affected as it is an expression of those favela communities,” says Adriana Facina, who has just completed her post-doctorate at the National Museum/UFRJ on leisure and popular music in Rio, with a focus on funk.

The UPP Brings the Market

As Adriana says, even with so much interest from specialists in doing “research with the favela” and not just in it or about it, the possibility of increasing consumerist culture is the principal draw for the government rather than encouraging the creation or expansion of public policies in education and culture in the favelas.

Linked to that, and bearing in mind the upcoming sporting megaevents (the 2014 World Cup and the 2016 Olympics) that are knocking at our door, the governments (municipal, state and federal – united under the aegis of an inseparable alliance) are focusing in on the future of the favela.

Linked to that, and bearing in mind the upcoming sporting megaevents (the 2014 World Cup and the 2016 Olympics) that are knocking at our door, the governments (municipal, state and federal – united under the aegis of an inseparable alliance) are focusing in on the future of the favela.

The authorities say that “recapturing favela territories is very important for the city as a whole”. The occupation of favelas by the Police Pacifying Units (UPPs) is what the Fluminense Federal University Professor of History Adriana Facina (the author of an article that looks at the social stigma attached to young funkeiros in the favela) calls “a package for the communities”. She adds: “the UPPs are more than just a public safety initiative, as they are also generating real estate speculation, contract interest for telephone and TV services, shop openings and cultural emergence.”

FLUPP and Local Cultural Production

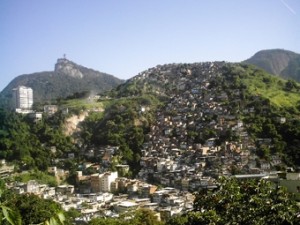

Another result of the UPP presence are the events that are organized by non-favela entities. One of these events, stemming from a mix of popular knowledge, academic research and increased market integration, took place at the Morro de Prazeres favela between November 7 and 11. One positive is that favela-based cultural producers have gained more visibility, albeit somewhat timidly.

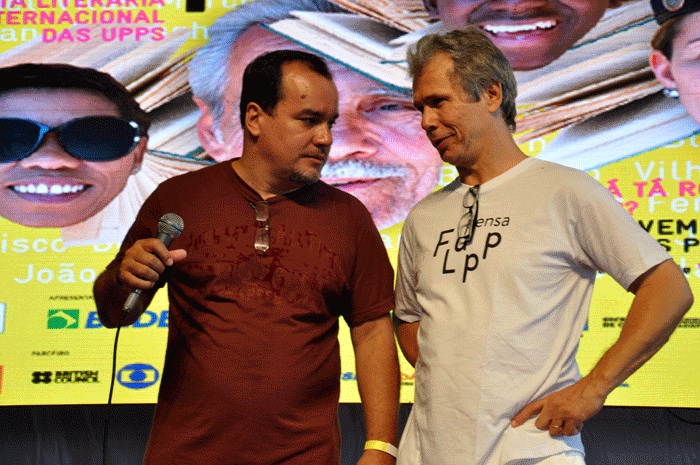

FLUPP, the UPP International Literature Festival, held its inaugural event without any pressure from the UPP commanders – it was not created and organized by the UPP (“we went to favelas without UPPs, such as Manguinhos and Vigário Geral, during the preparation for FLUPP Pensa which resulted in a book featuring 43 novice authors,” says Écio Salles, one of FLUPP’s directors), and it opened new horizons for literature throughout Rio de Janeiro. Previously, literature was the realm of a minority of cariocas [Rio residents]: generally wealthy whites, with a high level of education, coming from Rio’s more prosperous South Zone.

FLUPP, the UPP International Literature Festival, held its inaugural event without any pressure from the UPP commanders – it was not created and organized by the UPP (“we went to favelas without UPPs, such as Manguinhos and Vigário Geral, during the preparation for FLUPP Pensa which resulted in a book featuring 43 novice authors,” says Écio Salles, one of FLUPP’s directors), and it opened new horizons for literature throughout Rio de Janeiro. Previously, literature was the realm of a minority of cariocas [Rio residents]: generally wealthy whites, with a high level of education, coming from Rio’s more prosperous South Zone.

According to Júlio Ludemir, another of FLUPP’s directors, creating a different and expanded vision of the city through unconventional means was important in the festival’s organization: “There was a specific reason for doing it in the Morro dos Prazeres favela: it is a favela in the middle of the city. We wanted to avoid doing it in the South Zone (with its reputation for ‘beach-sun-beach’ sameness) and also we did not want it in a far-away place, which can bring logistical problems. The solution, then, was to hold it in a region with some cultural tradition – as is true in Santa Teresa neighborhood – and in a central community with a wonderful 360 degree view of the city. It was then that we incorporated the 360º concept to the FLUPP Project. And, moreover, it was symbolic to hold the festival in a community with that name.”

UPP Inhibits Community Parties

Eliza Rosa has been the President of the Residents Association of the Morro dos Prazeres for the last four years, and previously served as its secretary and treasurer. The latest problem caused by the Prazeres UPP was on Saturday November 17 when the Bonde da Nike party was scheduled to take place.

It was a community-organized event, similar to others that have taken place, which was free and going to take place in the community sports hall. Eliza had arranged the event and come to an agreement with the local UPP, and, given that and the number of invites distributed, she was sure there would be good attendance. However, that was not the case: “It so happens that the captain had authorized the event but was not around for it as he was on a course. A deputy of his did not want to let the event go ahead. But they all think they can use that space whenever they please, but it is a community space. I can already see the day when the UPP officers want to use the space, but the community will resist and not let them meet up there”.

As such, in the favelas the relationship between resident and government entities tends to expose thorns rather than flowers. Given the repeated intransigence of police power, the truth is that now favela residents where there is a UPP presence run the risk that whether events take place or not is exclusively at police discretion.

If Resolution 13 is approved then any event, from birthday parties to bailes funk – typical of favelas and favela youth – is in the hands of the UPP commander as to whether it should go ahead or not.

In September 2009, funk was given cultural heritage status and defined as a “cultural and music movement of a popular nature”, and backed by Law 5.543 by the majority of state deputies in ALERJ, the Legislative Assembly. This did mean that funk was no longer fully on the margins but, unfortunately, the agreement between the deputies and Apafunk (the ‘Professional and Friends of Funk Association’) has yet to legitimate all funk parties in UPP-controlled favelas: “The baile funk is viewed negatively by the majority of police commanders, and not just the UPP but by all police units in Rio. The bailes ended up in the favelas and, due to a lack of public policy, did not respect time and volume limits,” says MC Leonardo, the cofounder and now president of Apafunk.

In September 2009, funk was given cultural heritage status and defined as a “cultural and music movement of a popular nature”, and backed by Law 5.543 by the majority of state deputies in ALERJ, the Legislative Assembly. This did mean that funk was no longer fully on the margins but, unfortunately, the agreement between the deputies and Apafunk (the ‘Professional and Friends of Funk Association’) has yet to legitimate all funk parties in UPP-controlled favelas: “The baile funk is viewed negatively by the majority of police commanders, and not just the UPP but by all police units in Rio. The bailes ended up in the favelas and, due to a lack of public policy, did not respect time and volume limits,” says MC Leonardo, the cofounder and now president of Apafunk.

A migrant from Brasilia, Eliza has lived in Prazeres for 15 years and from day one has seen the routine difficulties facing the life of community residents: “With the UPP coming in it was expected there might be improvements. Unfortunately, so far there has been nothing at all. We used to have two people working with the water supply here, but with the ‘pacification’ they took away one of those guys. Now how are we supposed to all have water here if one guy on minimum wage and working eight hours a day has to take care of everything? Sometimes there is only good water really early in the morning”.

Before the next FLUPP – scheduled to start on November 20 2013 in Vila Cruzeiro – hope lies in the uncertain return of bailes and parties in the public spaces of “pacified” favelas. Because if there is any attempt to silence the baile funk, rest assured that there will always be a funkeiro around to “come back and defend our flag,” as MC Júnior and MC Leonardo put it.