Sunday, July 26, 2020, is the 30th anniversary of the Acari Massacre. On this day in 2020, the activities of the 5th Annual Edition of Black July (Julho Negro) will begin. Black July is an international movement against militarization, racism, and apartheid, based in Rio de Janeiro and organized by favela movements composed of mothers and relatives of victims of state violence, such as the Mothers of Acari (Mães de Acari). On July 24, activist movements connected to Black July conducted a Twitter campaign to raise awareness about the fight against the genocide of Afro-Brazilians, using the hashtag #ChacinaDeAcari30Anos (#AcariMassacre30Years).

As Madres de la Plaza de Mayo, da Argentina, procuravam seus filhos desaparecidos na ditadura militar. As Mães de Acari procuravam seus filhos desaparecidos na “democracia”. #ChacinaDeAcari30Anos

— Favela em Pauta (@favelaempauta) July 24, 2020

The Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo [in Argentina] searched for their missing children during the military dictatorship. The Mothers of Acari searched for their missing children in a “democracy.” — Favela em Pauta

On the night of July 26, 1990, a group of 11 young people, 7 of them minors, most of them black residents of the Acari favela in the North Zone of Rio de Janeiro, were visiting a country house in Suruí, in the municipality of Magé, in Greater Rio’s Baixada Fluminense region, when hooded men identified as police officers invaded the house and kidnapped them.

This crime happened only five years after the end of the military dictatorship. It has become known as the Acari Massacre. The policemen—the criminals responsible for these crimes and for many others—such as the Vigário Geral Massacre, in which 21 favela residents were executed inside their own homes while they slept, were part of an extermination group called Running Horses (Cavalos Corredores), that terrorized favela residents in the 1990s.

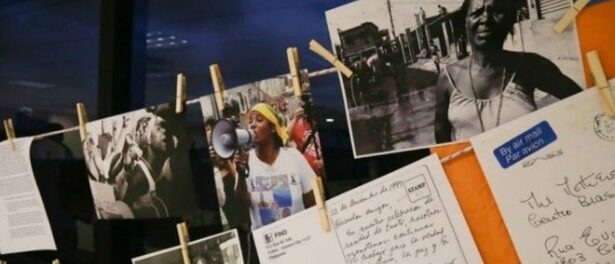

From that moment on, according to investigations at the time, nothing more could be proven about the crimes. No new evidence was gathered for the cases of these murdered youth. Their bodies were never found. In the nearby area, all that was found was a van that took the kids to the country house. The crimes of the Acari Massacre moved some of the mothers of victims of state violence to organize into activist movements. Mothers of Acari among them, these mothers’ pain fuels their resolve t0 fight against cases such as their children’s and to use activism to help heal the wounds caused by their loss (especially in these cases, this is an incomplete mourning—as the bodies were never found).

Thanks to the Mothers of Acari, their children’s cases have not been forgotten, neither by the state nor by the media. These mothers have acted as detectives, investigating the disappearances of their kids. This cost the life of one of these mothers: Edmea da Silva Euzébio, assassinated on January 15, 1993, in Praça XI, downtown Rio, three years after her son, Luiz Henrique da Silva Euzébio, had gone missing. Two other Mothers of Acari have been assassinated.

Acari foi a primeira favela a sofrer com uma chacina após a ditadura militar, esse ocorrido marcou o início das Mães de Acari, que iniciaram por conta própria a busca pelos filhos e por justiça. #ChacinaDeAcari30Anos pic.twitter.com/oPoB8yFR1t

— Luis Melo ❤✊ (@luismelo025) July 24, 2020

Acari was the first favela to go through a massacre after the end of the military dictatorship, this was the founding moment of the Mothers of Acari, who, on their own, started searching for their kids and for justice. — Luis Melo

The Acari Massacre is of utmost importance not only because it preceded many other massacres (Candelária, Vigário Geral, Nova Brasília, among others), but also because it unveiled a set of characteristics of structural racism working through public security agents in Rio de Janeiro who deal with black and poor populations, especially residents of favelas and urban peripheries. It reveals an analogous pattern of investigation, silencing and impunity that is responsible for the genocide of the black population, with the subtle “permission” of the state.

In 1994, Amnesty International Brazil identified involvement by military police officers of the 9th Military Police Battalion, in Rocha Miranda, and detectives of the 29th Civil Police Station, in Pavuna, in the disappearance of these young men and women from Acari. Nonetheless, according to the investigation at the time, no one was indicted due to the lack of evidence and also to the statute of limitation of the crime. In 2010, the case went cold with no one found guilty for the massacre. Until today, the military police battalion in the region of Acari is the leading killer of civilians during confrontations with state forces, as stated in the Amnesty International report Você Matou Meu Filho (You Killed My Son).

For Buba Aguiar, a member of the Fala Akari Collective, the Acari Massacre permeates her own life story. She says she “cannot recall exactly how many male friends [she] has lost in summary executions and slaughters,” as they were too many. She was born in the Baixada Fluminense, but raised in Acari. According to her, the history of the massacre is as if it were her own. That’s why she believes it’s her duty to carry on the fight of the Mothers of Acari.

“It is very sad to see that through this day, and I am now 28 years old, we have the same fight as those mothers. A fight for justice for a massacre that happened two years before I was born. Governments changed, and not only has the crime not been solved, but it has been perpetrated many other times. Residents of the favela of Acari still suffer at the hands of state agents. Now the executioners are others, but they are not less violent,” she says. And concludes:

A visão de que o Estado é o único monopolizador aceitável da violência na sociedade coloca no mesmo um manto de impunidade e com isso vemos ocorrer o que estamos vendo: uma chacina há 30 anos sem resposta #ChacinaDeAcari30Anos

— Buba Aguiar (@BuubaAguiar) July 24, 2020

“The view that the State is the only acceptable monopolizer of violence in society hangs a veil of impunity over the police and that’s why we see something like this: a 30-year-old massacre still unanswered” — Buba Aguiar

The 11 victims of the Acari Massacre are:

Rosana Souza Santos, 17 years old

Cristiane Souza Leite, 17 years old

Luiz Henrique da Silva Euzébio, 16 years old

Hudson de Oliveira Silva, 16 years old

Edson Souza Costa, 16 years old

Antônio Carlos da Silva, 17 years old

Viviane Rocha da Silva, 13 years old

Wallace Oliveira do Nascimento, 17 years old

Hédio Oliveira do Nascimento, 30 years old

Moisés Santos Cruz, 26 years old

Luiz Carlos Vasconcelos de Deus, 32 years old

Black July Online

Considering the global Covid-19 pandemic, the 5th Annual Black July will occur in a series of online activities held between July 26 and July 30, discussing how the Covid-19 pandemic aggravates racism, militarization and apartheid in the world. Check it out.

The 1st Annual Edition of Black July happened in 2016 with the participation of the U.S. Black Lives Matter movement. In the following year, the event’s central discussion was about the similarities between military occupations in Brazil, Haiti, and Palestine.

From this starting point, Black July has continued holding annual meetings, teach-ins and conferences with activists from Brazil, Palestine, Chile, Argentina, South Africa, Venezuela, Colombia, Mexico, India, and the Mapuche people, among others. The idea is to strengthen international solidarity in the fight against walls, borders and genocides.