This is the first installment of a two-part piece looking at a Brazilian Supreme Court case known as “ADPF das Favelas.” It discusses the effects of a legal opinion and a temporary order issued by Justice Edson Fachin and the significance of the case going forward. To read part II, click here. The series is part of our partnership with The Rio Times. For the report as published in The Rio Times click here.

As the new coronavirus has swept Brazil, its danger to the favela population has been well documented. Adding to this, Rio de Janeiro’s favelas experienced new spikes in a long history of police violence in April and May, and residents responded with new mobilizations. As part of the global Black Lives Matter movement, Brazilians across the country, including many favela activists, took to the streets to protest against structural racism and police violence.

Against this backdrop, an ongoing legal challenge against police violence in Rio’s favelas produced a number of critical decisions in Brazil’s Supreme Court (STF). These decisions not only saved lives in recent weeks, according to researchers, but they also create an opening to set powerful precedent for courts’ ability to check the actions of Brazil’s most lethal police force. The lawsuit is known as the ADPF das Favelas, and representatives of the coalition behind it discussed their efforts at a June 25 online panel.

Rio de Janeiro public defender Lívia Casseres described the lawsuit and citizen mobilization behind it as important correctives to a judicial system that would be better described as a “system of injustice” toward favela residents.

An Upward Trend of Police Killings

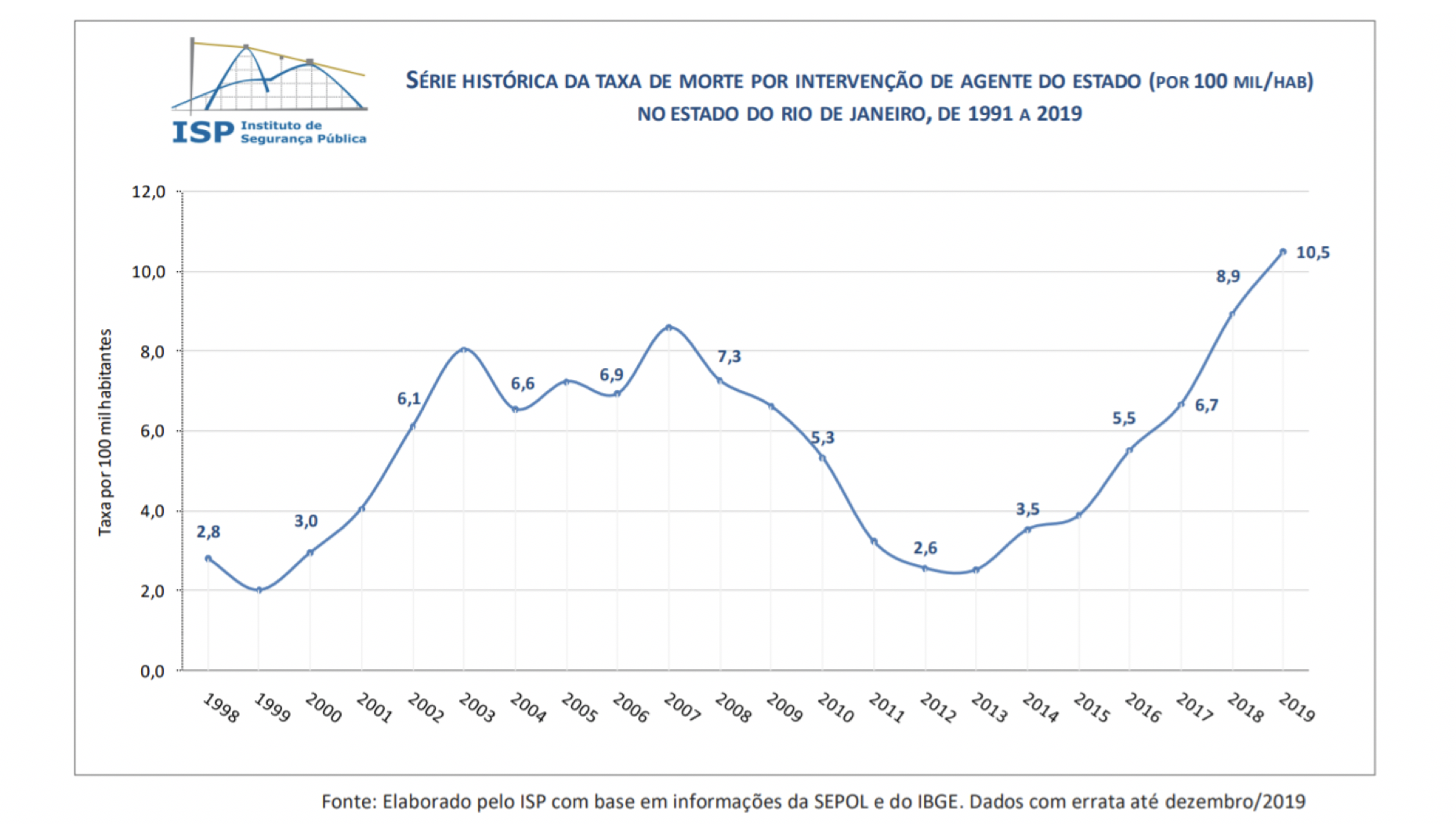

Yearly official totals of killings by police and other government officers in the state of Rio have been on a general upward trend since 2013, when an effort at police reform in the state began to fray. At that time, police were responsible for around 13% of the state’s homicides. In 2017, police killed more than 1,000 people for the first time since 2009, and during a federal security takeover in the state in 2018, police and military officers killed 1,534 people, amounting to 28% of the homicides that year. Around 17 million people live in the state. In 2019, police killed 1,814 people under newly elected governor Wilson Witzel, who told police to “aim at the little heads” of criminal offenders and “fire.” Killings by police accounted for almost 40% of homicides in the state last year.

At the online panel, Wallace Corbo of NGO Educafro called the state’s security policies “genocidal.” Many panelists emphasized the disproportionate toll of such policies on Afro-descendent Brazilians. Though around 56% of Brazil’s population is black or brown, 80% of people killed by police in the state of Rio in the first half of 2019 were black or brown. The percentage is consistent with sustained figures over many years; a 2015 analysis by state legislators of 3,421 police killings since 2010 found 80% of the victims were black or brown.

Despite the frequency with which police in Rio de Janeiro kill people, forensics teams tasked with investigating these deaths operate on a shoestring budget and there is no concerted government effort to monitor the operations during which many of these deaths occur. That task falls to nongovernmental monitoring groups like the Fogo Cruzado data collection platform, the Network of Security Observatories (ROS), and the Center of Studies of Security and Citizenship (CESeC) at Cândido Mendes University. They track newspapers, news sites, social media networks and individual sources, sharing regular reports and analysis.

In March, as the new coronavirus arrived in Brazil, Rio police operations and killings dramatically decreased. But in April and May, police killings spiked, rising higher than the totals for the same months in already record-breaking 2019. May was also marked by a series of police killings of teenagers, including 14-year-old João Pedro Mattos Pinho in São Gonçalo and an operation which killed 13 people in Complexo do Alemão. These same police operations had been regularly interrupting community Covid-19 relief efforts.

“Now is the time to take care of people in need of basic food supplies,” said Eliene Vieira, an activist with the group Mothers of Manguinhos, “not for taking advantage of this time when everyone is inside their homes to [show off] military power.”

A Landmark Legal Challenge

In 2019, in response to the security policies of newly elected Rio governor Witzel, human rights lawyers partnered with the Brazilian Socialist Party (PSB) to mount a legal challenge against those policies that soon gained the support of a coalition of civil society groups. It took the form of a Claim of Noncompliance with a Fundamental Order (ADPF), an allegation that a government body has violated a fundamental element of the Brazilian constitution.

This ADPF, number 635, has come to be referred to as the ADPF das Favelas (The Favelas’ ADPF), and is historic in its recognition of favela collectives as amici curiae (collaborators with the court based on their special expertise). The Network of Communities and Movements Against Violence, Coletivo Papo Reto, Redes da Maré, Coletivo Fala Akari, Mothers of Manguinhos, and the Right to Memory and Racial Justice Initiative are the first groups from favelas to participate in a lawsuit against the State of Rio de Janeiro in the Supreme Court.

The subject of the ADPF das Favelas lawsuit is “excessive and growing police lethality” in the state of Rio de Janeiro, “directed, above all, against the black and poor population of favelas.” It cites “the relationship between structural racism and police lethality.” The amici curiae, including the favela collectives, the Rio de Janeiro State Public Defender’s Office, the Unified Black Movement (MNU), and human rights organizations Conectas, Justiça Global, and ISER, wrote in an April 16 brief that the actions of the Rio police threatened “socially vulnerable groups” including “favela residents, black people, poor people, children, adolescents, young people, the elderly, women, and police.” They wrote that actions by Rio’s police have violated the UN’s Code of Conduct for Law Enforcement Officials, which stipulates that use of force should be proportional, exceptional, and only deployed when absolutely necessary.

The lawsuit calls for measures such as limiting police operations in the proximity of schools, day cares, and health centers, reducing sweeping warrants for forced police entry into homes, prohibiting shooting downward into residential areas from helicopters, ensuring first aid for people injured in police operations, preserving crime scenes after the operations, improving external control over police actions by the state public prosecutor, and an end to government encouragement of police violence.

“I would like the STF to see this with the eyes of the favela,” Vieira said. “We are subjects with rights and every time there are these operations inside favelas, our rights are violated.”

Furthermore, she said that during the pandemic, children who would usually spend their days inside a school building are in their homes or in city streets, and thus at higher risk of being shot during daytime police incursions: “When the operations happen, the first to be hit [with bullets] are the children.” Activist Renata Trajano of Coletivo Papo Reto and the Alemão Crisis Center called for the Court to approve the ADPF das Favelas so that “young people can sit in the alley by their houses and have a chat […] without having to have a gun aiming at their heads the whole time.”

On April 17, Supreme Court Justice Edson Fachin, who is overseeing the case and was the first to issue an opinion, voted in favor of enforcing several of its requests, including those on restricting the use of police helicopters, preserving crime scenes, restricting operations near schools and health centers, and guaranteeing external investigations of police suspected of committing crimes. He also voted to suspend a decree by Witzel that had halted bonuses for police whose record showed a reduction in the number of citizens they killed.

As the Supreme Court case slowly continued, with other judges yet to issue their opinions, lethal police actions continued in April and early May. Analysis by ROS found that Rio police killed 57.9% more people in April 2020 than they did in April 2019, and by May 19, the police had killed 16.7% more people than they did in the first 19 days of May 2019.

In response, on May 26, the team behind the ADPF filed a petition for an emergency temporary order to suspend police operations during the pandemic except in “absolutely exceptional” circumstances which must be justified in advance to the public defender’s office, and in which “exceptional care” must be taken not to put favela residents and services in a position of “even greater risk”. The document made explicit and detailed reference to the killing of 13 people in Complexo do Alemão on May 15, the death of 14-year-old Mattos Pinho on May 18 inside his aunt’s home—and in the company of five other adolescents—the death of Iago César dos Reis Gonzaga, 21, allegedly tortured before police shot him in Acari, and the May 21 death of 19-year-old student Rodrigo Cerqueira, killed amid a distribution session of emergency Covid-19 food relief to residents of Morro da Providência.

On June 5, Fachin issued the emergency temporary order—reserved for cases where rights are in immediate and serious danger—suspending police operations in Rio favelas for the duration of the pandemic.

This is the first installment of a two-part piece looking at a Brazilian Supreme Court case known as “ADPF das Favelas.” Click here to read Part II, discussing the effects of Fachin’s temporary order at reducing police killings and the broader significance of the case.

Featured Photo: Luna Costa

Support our efforts to provide strategic assistance to Rio’s favelas during the Covid-19 pandemic, including RioOnWatch’s tireless, critical and cutting-edge hyperlocal journalism, online community organizing meetings, and direct support to favelas by clicking here.