This is our latest article on Covid-19 and its impacts on the favelas.

This year, amidst the coronavirus pandemic, the education sector, like all aspects of human life, was forced to gaze inwardly and reinvent itself, improvising as needed. After a series of investment cuts in federal universities, the goal of including black, poor students from favelas and urban peripheries has yet to become a reality in Brazilian public universities.

With the impossibility of returning to in-person classes, preferences for how to proceed vary among students. 28-year-old Augusto Moreira Vasconcelos, a resident of Morro do Guarabú in Complexo do Dendê, on Ilha do Governador in Rio de Janeiro’s North Zone, studies social sciences at the Federal Rural University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRRJ). He said, “There is a schism within the student body. Students from the most traditional majors, who generally have higher incomes, such as agronomy, engineering, and most Bachelor of Science programs, want classes to be resumed remotely as soon as possible. However, students in majors that are mostly attended by low-income black students, such as languages, history, and social sciences, have been starkly against online classes, as they know that many among them do not have access to the internet.”

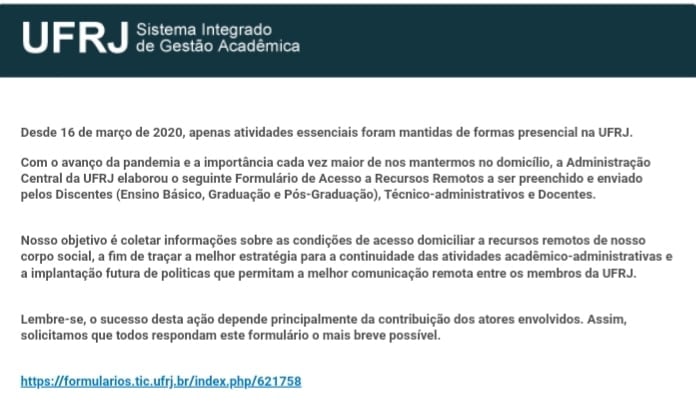

Before planning for any scenarios, officials at universities such as the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ) and Federal Fluminense University (UFF) recognized that they lacked key information about their own students, professors and staff, so, over several months, they conducted research to outline the socioeconomic profiles of students and their access to adequate domestic structure for studying from home, which includes having electronic devices and a broadband Internet connection. This research used phone calls and online forms as tools for gathering data. Phone calls played a key role in the process, as the universities were trying to reach those students with no regular access to their email accounts during quarantine, away from both the universities’ computer labs and free Wi-Fi zones.

Bearing the results of this diagnostic research in mind, UFRJ’s vice-president Carlos Frederico Leão Rocha told the press, in July, “45% of our students are living off less than 1.5 times the minimum wage as their whole family income. And we have a set of problems related to access that are quite relevant. 98% of our students have access to the Internet, but when it comes to broadband connection, we do have an issue. Broadband is necessary [for participating in online classes] due to elevated data usage [it would not suffice to have limited mobile data bundles].” Because of this, financial aid is fundamental to almost half of UFRJ’s students. The federal government’s recent policy of disinvestment in education exacerbates this reality.

Bearing the results of this diagnostic research in mind, UFRJ’s vice-president Carlos Frederico Leão Rocha told the press, in July, “45% of our students are living off less than 1.5 times the minimum wage as their whole family income. And we have a set of problems related to access that are quite relevant. 98% of our students have access to the Internet, but when it comes to broadband connection, we do have an issue. Broadband is necessary [for participating in online classes] due to elevated data usage [it would not suffice to have limited mobile data bundles].” Because of this, financial aid is fundamental to almost half of UFRJ’s students. The federal government’s recent policy of disinvestment in education exacerbates this reality.

At the State University of Rio de Janeiro (UERJ), a pioneering institution when it comes to affirmative action in Brazil, a more comprehensive profile of the students already existed. The university’s Central Students’ Union (Diretório Central dos Estudantes, the DCE), together with the university administration, approved, in the beginning of July, emergency aid paid in a single installment of R$600 (around US$115) to all students accepted through its affirmative action policy. This sum is preferably to be used for digital inclusion or to buy books, notebooks, and other academic supplies. This aid comes in addition to a monthly scholarship given to students committed to completing their studies (bolsa permanência). The aid was approved even before online classes became an official topic of discussion. Additionally UERJ’s President’s office agreed that, in the event of an online semester, the university would guarantee access to technology to all. There are even some unconventional ideas being brought forth at UERJ, such as a petition by the DCE to the state Public Prosecutor’s Office and to the federal tax agency requesting that technological devices apprehended by authorities in relation to unlawful activities be given to the UERJ affirmative action beneficiaries and other students from vulnerable backgrounds.

However, other universities, such as UFRRJ, UNIRIO, IFRJ, CEFET-RJ, UEZO and UENF, are still weighing possibilities and have earned criticism for their indecision. While positions remain undefined, students are demanding that the universities bear in mind an important principle. Allanis Pedrosa of the State of Rio de Janeiro’s Students’ Union said, “We cannot push students into a place of more vulnerability than the one they are already in. We cannot abandon working class students in a moment like this… It’s useless to only think about digital inclusion. Even having all resources at hand, how can one guarantee, for example, that students who live with their whole family in a single-room house will be able to concentrate [enough to study]? Or the concentration of a student who is a single mother and has to stay home with her kid full-time during the pandemic? Or of students with delicate mental health issues? What are the universities’ plans to ensure to such a youth their dream of achieving a university diploma?”

The anxiety levels caused by the uncertainty and delays in decision-making by university presidents’ offices put in check the mental health of students who are black, poor, and residents of favelas or urban peripheries. This exacerbates inequalities, as Vasconcelos analyzed: “We have no longview. They say there will be online assemblies, but nothing is yet decided. Nothing is happening… this is very frustrating, all this lack of clarity. I want to graduate, but I don’t know if there will be classes and [even if there are] whether I will be able to attend them.”

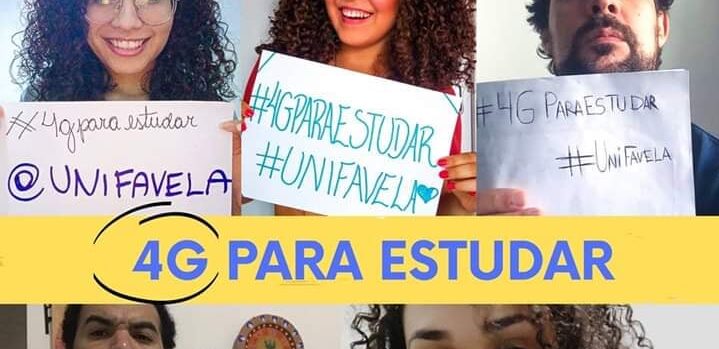

Universities such as UFRJ, UFF and UERJ decided to hold the semester remotely in August and September. This will be an optional semester, primarily directed to students who are on the verge of graduating. These universities published a call for applications for financial aid for the purpose of digital inclusion as a precondition for such a semester to happen. Michele Ferreira de Oliveira, 27, a UFRJ Languages (Portuguese and Arabic) major and a resident of Parque Centenário, in the area of Complexo da Mangueirinha and Favela do Sapo, in the city of Duque de Caxias, in Greater Rio’s Baixada Fluminense region, affirmed she will only be able to attend online classes because of these policies aimed at granting access to students. “When I heard about the possibility of going back to classes remotely I confess that I became apprehensive, because I didn’t know if I would be able to handle it or not, due to the fact that we don’t have [broadband] Wi-Fi at home,” she said. “I didn’t know if my mobile bundles and Internet data packages would be enough for the classes. These bundles are also shared with my parents, and they are limited. The connection isn’t good either, the signal is often intermittent. We have no financial means to pay for better quality Internet. The university providing SIM cards and other devices for those without the means is a beacon of hope for students like me, with financial problems. I think it is a great alternative and initiative. It gave me hope that I’ll be able to go on with my studies, even during this chaotic period.”

Universities such as UFRJ, UFF and UERJ decided to hold the semester remotely in August and September. This will be an optional semester, primarily directed to students who are on the verge of graduating. These universities published a call for applications for financial aid for the purpose of digital inclusion as a precondition for such a semester to happen. Michele Ferreira de Oliveira, 27, a UFRJ Languages (Portuguese and Arabic) major and a resident of Parque Centenário, in the area of Complexo da Mangueirinha and Favela do Sapo, in the city of Duque de Caxias, in Greater Rio’s Baixada Fluminense region, affirmed she will only be able to attend online classes because of these policies aimed at granting access to students. “When I heard about the possibility of going back to classes remotely I confess that I became apprehensive, because I didn’t know if I would be able to handle it or not, due to the fact that we don’t have [broadband] Wi-Fi at home,” she said. “I didn’t know if my mobile bundles and Internet data packages would be enough for the classes. These bundles are also shared with my parents, and they are limited. The connection isn’t good either, the signal is often intermittent. We have no financial means to pay for better quality Internet. The university providing SIM cards and other devices for those without the means is a beacon of hope for students like me, with financial problems. I think it is a great alternative and initiative. It gave me hope that I’ll be able to go on with my studies, even during this chaotic period.”

Some students at these institutions, nevertheless, criticize the pace at which such initiatives have taken place. They also criticize that this aid won’t reach all students in need, as it should. According to Rebeca Santos Maria Vieira, 20, an Education major at UFF, “I think this aid is very important, it is worth it, but there are flaws. This is the big issue here. There had been enough time to find a way to assist everyone, but we must also understand that, with the budget cuts, things get harder.”

Another recurring critique is that the pandemic made more evident the inequality that had always existed at these universities. As Adriano Mendes, 24, a Master’s student in UFRJ’s Urban Planning graduate program and a resident of Complexo da Maré, in the North Zone, pointed out, “This kind of financial aid has been conceived later than it should have been. It could have been granted to the students as soon as they got into college. Imagine how interesting it would be if all students were given a computer when enrolling in university! But as years go by, we have a smaller and smaller budget for student aid. Then, how do we deal with this reality?”