This is our latest article on the Covid-19 and its impacts on the favelas.

Residents of the Complexo do Viradouro favelas of Niterói, Rio de Janeiro’s sister city across the Guanabara Bay, were surprised by the challenges of living through the Covid-19 pandemic alongside another “new normal”: that of an ongoing police occupation. Since August 19, residents have been under the control of the Special Operations Command (COE), the Canine Action Batallion (BAC), the Shock Police Batallion (BPChq), and the Special Operations Battalion (BOPE, akin to the SWAT in the United States). The operation is taking place even in the time of Brazilian Supreme Court order ADPF 635, which has suspended police operations in favelas of Rio during the Covid-19 pandemic.

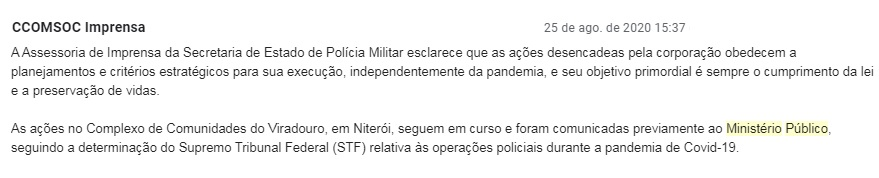

The ongoing operation “was communicated ahead of time to the Public Prosecutor and is set to continue for an indefinite period of time,” the State Secretary of Military Police told RioOnWatch in a statement.

“The community did not oppose the operation at the outset, but after two days of violations, residents began to give visibility to police abuses,” explained José.*

Fifteen days ago, RioOnWatch received reports and complaints of police violence from residents. They are abuses committed at any time of day: physical and verbal assaults, invasions of homes, abusive searches, and even torture by state public security agents.

“I feel afraid of going through a situation of police occupation, where you are not sure of anything. You leave the house and don’t know what will happen, whether they will enter your house [while you’re one] or not. There are reports that they not only invaded homes, but verbally assaulted women and that there were even physical attacks. There was a neighbor who saw them [the police] entering a resident’s house and shouted a warning: ‘That’s a resident’s house. Don’t do that!’ They did it! And they even went there to attack that lady. It’s a terror!,” said João.*

The atmosphere is very fearful inside the community formed by Largo da Garganta and various favelas on hillsides: Africano, União, Papagaio, Viradouro, and Cruz. With Morro do Zulu and Atalaia as neighboring communities, they are all located between Santa Rosa, Pendotiba and São Francisco, with access through Estrada da Garganta and Estrada Cachoeira, in Niterói.

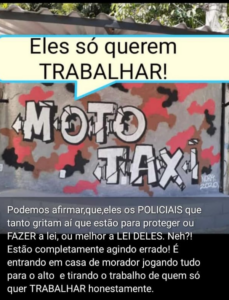

“Unfortunately, this is a pattern of police behavior towards those who live inside the communities. And we live through this on Wednesday, Thursday, Friday, Saturday, Sunday… The moto-taxi drivers wanted to work and they didn’t let them. They [the police] didn’t just prevent them, they even threatened to throw grenades at the moto-taxi point. Absurd,” said José.

“Unfortunately, this is a pattern of police behavior towards those who live inside the communities. And we live through this on Wednesday, Thursday, Friday, Saturday, Sunday… The moto-taxi drivers wanted to work and they didn’t let them. They [the police] didn’t just prevent them, they even threatened to throw grenades at the moto-taxi point. Absurd,” said José.

According to him, motorcycle taxi drivers had to move to another location farther down José Gomes da Cruz Street to be able to work and serve residents. Motorcycle taxi drivers have been recognized as an official profession in Brazil, regulated by law, since July 2009.

The so-called ADPF das Favelas Supreme Court decision is a symbolic victory for social movements and favelas. But despite restricting police operations under penalty of civil and criminal accountability during the Covid-19 pandemic, it leaves room for the use of state security forces, a window for these police operations to be carried out in “exceptional” cases. In case such an exceptional need is to be claimed, however, the security forces must first communicate notice to the Public Prosecutor’s Office, informing the conditions of this exceptionality.

That is exactly what the Military Police has been doing in several favelas throughout the Greater Rio metropolitan region since the ADPF came into force. As required, the Military Police sends a prior notice to the Public Prosecutor—responsible for the external control of police activity—informs the exceptionality, and acts. We have a new standard of action for the State Secretary of Military Police under the ADPF.

In some of Brazil’s public security institutions, there exists a culture that external checks should be handled after and not prior to the fact. In this way, the ADPF can be interpreted as a protocol for the notification of exceptionalities, and not necessarily a request for the authorization of action from the Public Prosecutor.

The ADPF restricts actions in favelas during the pandemic. Therefore, it helps prevent police missteps through the mandatory submission of a justification, which facilitates possible external supervision and evaluation by the Prosecutor’s Office and Supreme Court. At the same time, however, it does not totally prevent police occupations of favelas, because a prerogative remains for the State to act in “exceptional cases” in the realm of public security.

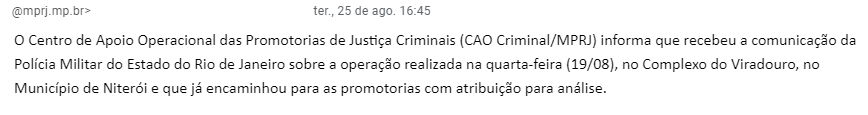

The statement sent by the Center for Operational Support of Criminal Justice Prosecutors from the Public Prosecutor reveals this game. When reached by RioOnWatch, the institution confirmed that it received confirmation of the operation in Complexo do Viradouro from the Military Police on August 19, and that it “forwarded the case to the prosecutors with attributions for analysis.”

Meanwhile, João’s days remain ruled by this “new normal,” not only due to the effects of the global health crisis, but also due to a police occupation in the middle of the Covid-19 pandemic.

“Every day it gets worse. [On August 30] there was a case here of a guy who got captured and badly beat. They broke his ribs, cut [him] with a knife. That was at night. And you don’t know… yesterday it was him, tomorrow it could be me. You don’t know what’s going on. You leave for work and when you come back… you don’t know. What legislation is this that authorizes a policeman who is circling, at nearly midnight, on the hill to pick up anyone, randomly, to beat up? To enter the resident’s home without a court order? It’s all wrong, right?” João said.

RioOnWatch reached out to the Military Police of the State of Rio de Janeiro (PMERJ) to find out what exceptionality justified the decision of a police operation in Complexo do Viradouro. According to the newspaper O São Gonçalo, the decision behind the police occupation was due to supposed extortion by local drug traffickers in exchange for access to public services. Yet, the State Secretary of the Military Police did not confirm this information. They just said that the “exceptionality” followed the legal requirements and that the decision rests with the Public Prosecutor’s Office.

In this context, RioOnWatch again sought out the Public Prosecutor. By email, we asked the following questions: “What was the exceptionality presented for a permanent and continuous occupation by PMERJ of Complexo do Viradouro? Was the Prosecutor aware that the operation on August 19 was treated like a police occupation? Did PMERJ inform them that the operation was of “indefinite length”? Ten days passed with no response.

In this context, RioOnWatch again sought out the Public Prosecutor. By email, we asked the following questions: “What was the exceptionality presented for a permanent and continuous occupation by PMERJ of Complexo do Viradouro? Was the Prosecutor aware that the operation on August 19 was treated like a police occupation? Did PMERJ inform them that the operation was of “indefinite length”? Ten days passed with no response.

“We Expected Public Works, Not Police!”

Residents of the Viradouro Complex were anxiously awaiting the start of infrastructure projects promised by the City of Niterói, with an investment of R$50 million (US$9.5 million). The improvement project foresees the building of containment slopes and improved sanitation, the installation of a digital urban platform, a technical school, a cultural center, a multi-sport court and three new community spaces with leisure equipment. However, along with the dreams of improvements, along with the construction, a foot kicked in the front door.

One of the courts with gym equipment for the elderly was destroyed. It will give way to a police booth. Divided into three phases, the police occupation in the Viradouro Complex foresees the installation of two police booths for the permanence of continuous policing in the region.

“We expected public works, not police! But apparently, they took advantage of the justification of construction to send the police. Instead of them [police] gaining support, they are losing their prestige in the community because of the way this operation is being carried out,” affirmed José.

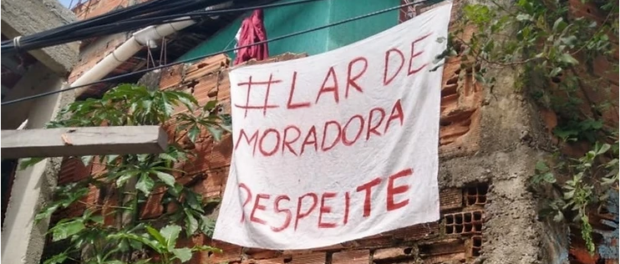

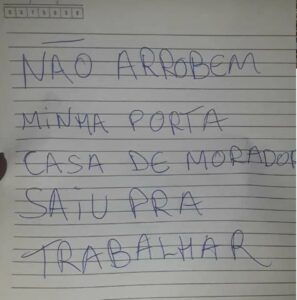

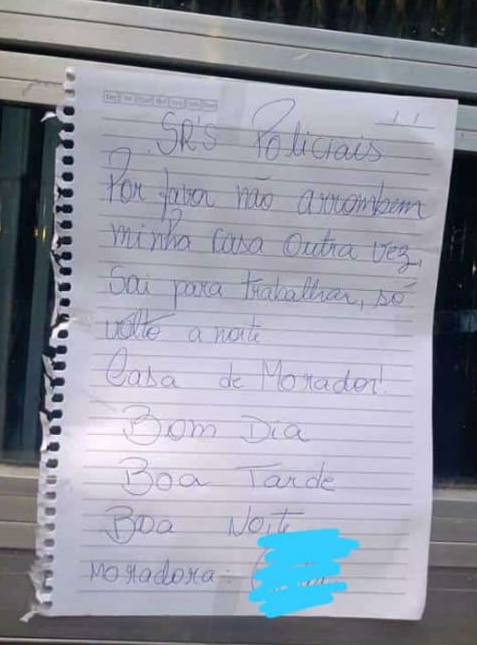

In front of the houses invaded by the police, residents started pasting handwritten notices on the doors asking for respect: “Police officers. Don’t break into my house again. I left to go to work. I’m only coming back at night. Home of a Resident. Good morning, Good afternoon, Good night. [Signed,] Resident.” The notices are cordial as a form of mediation against the rifles, hooded men and brutality. Some even draw hearts on the notes.

The police abuses follow a pattern. Upon entering the community, if the house is closed, the door is broken in. Inside the houses, the police throw things in the air searching everything, including electrical circuit breakers. They break plaster ceilings, eat food from the resident’s refrigerator, and even steal things that they judge to be of value. “Small business owners were missing money, products from inside the house and from their businesses. It is this routine that occurs in the communities, in addition to abuse of the elderly. They entered the woman’s house screaming in ignorance,” said José.

The police abuses follow a pattern. Upon entering the community, if the house is closed, the door is broken in. Inside the houses, the police throw things in the air searching everything, including electrical circuit breakers. They break plaster ceilings, eat food from the resident’s refrigerator, and even steal things that they judge to be of value. “Small business owners were missing money, products from inside the house and from their businesses. It is this routine that occurs in the communities, in addition to abuse of the elderly. They entered the woman’s house screaming in ignorance,” said José.

The climate within the community is one of panic. Residents fear police reprisals. José only decided to speak because he hopes that the exposure of this violence will help curb the abuse and prevent a tragedy. And also to “gain a voice and be able to breathe.” He clamored: “There has to be someone to shout for us! Because our voice is very difficult to be heard by our elite.”

According to the newspaper O Globo “the operation would have started at the request of Mayor Rodrigo Neves to Governor Wilson Witzel,” with authorization from the police command as part of a request from the City of Niterói to carry out the construction. “We in the community only know what comes out in the press. Until now no one knows the real reason for this,” said João.

“When we heard about the operation at Complexo do Viradouro, we understood that it was urgent to demand explanations from City Hall and the Military Police. We also consider it necessary to resort to the Public Prosecutor, the Public Defender’s Office and the National Council of Human Rights to verify the legality of this operation, since a decision by the Supreme Court prohibits police operations in the context of the pandemic, except in exceptional circumstances, which, in this case, are not clear,” said the president of the Human Rights Commission of the City Council of Niterói, Councilman Renatinho do PSOL.

He sent letters to the Niterói city government and the 12th Military Police Battalion asking for clarification about the police occupation at the Viradouro Complex, on August 20. Among the questions, the councilman asked: “Did the City of Niterói in any way request, recommend or encourage the occupation of the Viradouro Complex by PMERJ? On what terms will City Hall collaborate with the aforementioned occupation of the Viradouro Complex?” The letters have a response deadline of 20 days, extendable for another ten.

Federal congresswoman Talíria Petrone and state congressman Flávio Serafini, lawmakers representing the city of Niterói, also sent letters on August 25. They ask for an appointment with Mayor Rodrigo Neves, in the presence of Colonel Sylvio Guerra, commander of the 12th Battalion of the Military Police.

Residents Mobilize #RespectResidentHomes

On August 26, residents held the protest “Us for Ourselves at Morro da União” organized and carried out by black women of the community, who produced signs made of sheets to be placed on the windows and walls of resident homes with the hashtag #LarDeMoradorRespeite (#RespectResidentHomes).

Residents also pamphleted homes to raise awareness of police abuse. They are using a strategy of whistling when police officers enter the homes to search, so that other residents go to the house in question and supervise the work of the police. “It’s us for us…The whistle is coming from Carol’s house, let’s go to Carol’s house to show that this resident is not alone. When the police enter our house, we say so. The police entered Larissa’s house and Larissa spoke, shared it with everyone here… But that was afterward. The idea is that we have to act before [the police enter]… [The police officer normally argues] ‘Ah, but I’m just looking.’ Yeah, but you will look with a ton of residents watching you,” explains a resident in the video Us for Us. The #LarDeMoradorRespeite resistance movement started at Morro da União and inspired other black women from other favelas that form the Complexo do Viradouro.

Answers Don’t Come

Hearing only silence from public authorities, on September 2, federal congresswoman Talíria Petrone and state congressman Flávio Serafini sent a letter to Supreme Court Minister Edson Fachin, questioning the legality of the Military Police’s action in Complexo do Viradouro. Fachin is the presiding judge of the temporary hold order that was endorsed by the court by 9 votes on August 4.

Parliamentarians also met with residents of several favelas in Niterói at the Public Defender’s Office, according to a Facebook post on September 4.

https://www.instagram.com/tv/CEu8keKpjMC/?utm_source=ig_embed

“Upgrading work in favelas is very welcome. However, why were they announced just now, after eight years of government, in the middle of a pandemic, and on the eve of a municipal election? Was this project built in a participatory manner with the local population? The fact is that nothing, not even construction, can justify abuses, arbitrariness or police violence,” affirms Renatinho.

The criticisms of the Complexo do Viradouro residents were sent to the National Human Rights Council, to the Human Rights Commission of the Rio de Janeiro State Legislative Assembly (Alerj), to the State Public Defender’s Office and the State Public Prosecutor.

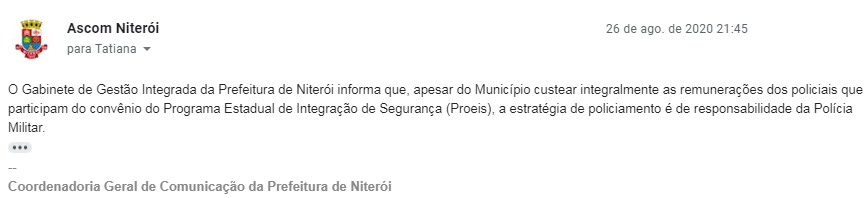

RioOnWatch contacted the City of Niterói. By email, we asked about the deadline for completion of the works and the motive for the police occupation in the Viradouro Complex. We also ask for clarification regarding the information that the occupation would have made at the request of Mayor Rodrigo Neves in a meeting with the governor of Rio, Wilson Witzel. However, none of these questions have been answered. The statement sent by the City of Niterói only states that:

The Cabinet of Integrated Management of the City of Niterói informs that, in spite of the City fully paying the salaries of police that participate in the State Security Integration Program (Proeis), the policing strategy is the responsibility of the Military Police.

It is noteworthy that RioOnWatch did not ask the City questions about the State Security Integration Program (Proeis). Through an agreement with the State, the mayor of Niterói increased the number of Military Police officers working on the perimeter of the city, with all the costs of PM compensation being paid in full by the City of Niterói.

“By the end of 2020, R$300 million (US$57 million) will have been paid in public security. It is the largest investment by a city hall in this area in Brazil. We invest in security more than many states and the results are positive,” affirms Mayor Rodrigo Neves, in an article on the City’s news portal.

Colonel Sylvio Guerra, in the same news report, states: “Niterói is smiling again due to this partnership between the 12th Battalion and the State of Rio de Janeiro with the municipality of Niterói. This partnership of ours has been successful and we still have lots to do.” The news item refers to the expansion of the Proeis program in December 2019.

The city of Niterói is the rich neighbor of Rio de Janeiro. And it is proud to boast the seventh-highest Human Development Index ranking in the whole country. According to the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE), its GDP per capita in 2017 was R$55,000 ($10,500), while at the national level the per capita average was a little more than R$31,000 (US$5,920) that same year, as pointed out in a report by El País. But, what the rich cousin of Rio de Janeiro does not emphasize is that the high-level of quality of life—which includes the right to public security—for the city has a color and a class: white and upper-middle class.

According to data from the Public Security Institute (ISP) analyzed by Casa Fluminense, 60% of all violent deaths that occurred in 2019 in Niterói were committed by police officers from the State of Rio. In total, 88% of the victims were black. It is the highest percentage in the whole of Brazil (75.4%) and in the metropolitan region of Rio (79%), higher than Rio de Janeiro proper (81%).

In absolute numbers, in Niterói alone, the police killed 125 people. Of these deaths, only 15 were white people. The city of Niterói is one of the most segregated in Brazil, according to Nexo.

“The fact is that we live in a city in which the main victims of State violence are the poor and black population, from favelas and peripheries. It is not by chance that Niterói is the national champion city in racial inequality, according to a survey by the newspaper Nexo,” emphasized Renatinho.

Creative Mobilization: Viradouro’s Artistic Cultural Occupation

While the responses from the Supreme Court, the Public Defender’s Office, and the Public Ministry do not arrive, the residents decided to act. On September 5, at the Pracinha of the Viradouro Complex, they held the first edition of the Viradouro Cultural Artistic Occupation (OCA). It was a form of resistance to police occupation and the absence of respected rights: the right to life, the city, and housing within the favelas.

The initiative featured artistic presentations from various genres of artists from the community. Among them was the singer Buiú, who released a CD in 2000, the drums of Folia do Viradouro, and participation by the organization Conexão Favela & Arte that works with rap, hip hop and slam in the favela. OCA is supported by the Residents’ Association, which provided pogo sticks and games for children.

“The authorities have decided to occupy our territory with weapons, rifles, police officers, and they still want to install armored cabins to surveil us. They say it is for our safety, but where it happened it only generated insecurity… and deaths! Where is Amarildo, [the favela of] Rocinha still asks today,” says the manifesto of OCA—Viradouro Cultural Artistic Occupation.

One of the organizers of the artistic occupation is Alessandro Conceição, 37, a resident of Morro da União, who made it clear: “We are not against the construction, and to think that is very reductionist. The public works should have already taken place. They’re already late. As government officials, it is their responsibility to do the construction, whether in Viradouro or in other communities. It’s an obligation! Nobody was ever against the construction.”

For Conceição, the problem is the use of the construction as a means to put into practice a police occupation to control the community, a model of public security that resembles the failed UPPs.

“This is a racist discourse of social control. As a black favela resident, I feel that this discourse of racism and slavery is still perpetuated by the authorities. It is very sad that you have to deal with the common idea that since Niterói is a middle class city with a majority white middle class, you know that these people feel that this [police occupation in the favela] will make their lives better. In other words, they will be able to walk on the streets with their cell phones and watches, because people like us in Viradouro are being controlled by the police they invented. Therefore, I feel disrespected, criminalized as a person, marginalized,” he protested.

“There was a moment in which we were very happy when the Supreme Court approved the ADFP, which prohibited operations in favelas. This gave hope to those who live in the favelas, but we have seen that it is not exactly like that, right? Not only here in Viradouro, but in other communities: they [the police] have found new loopholes. For me, it gives me a feeling of extermination, of tiredness, especially for the black, poor favelado, and peripheral populations,” criticizes Conceição, who is a member of the Center for the Theater of the Oppressed.

*João, José and Maria are all fictional names used by RioOnWatch to protect the security of residents of the favelas of Complexo do Viradouro.

Photos of #LarDeMoradorRespeite (#RespectResidentHomes) by Gabriel Horsth

Photos of the Viradouro Cultural Artistic Occupation (OCA) by Rafael Lopes