Clique aqui para Português

This is our latest article on Covid-19 and its impacts on the favelas.

Around 2.5 million people live in favelas in Nairobi, the capital of Kenya in Africa, and 1.4 million in the city of Rio de Janeiro, in Brazil. Beyond the shared difficulty of accessing public services in these territories—such as basic sanitation, for example—there are also threats of forced evictions, the State’s systematic negligence of basic rights, and the stigmatization of the local population by parts of society. Above all, from Nairobi to Rio, the police kill. Including during a pandemic.

This tragic scenario was recounted by human rights activists from the Mathare Social Justice Center (MSJC) in Nairobi and from the Straight Talk Collective (Coletivo Papo Reto), a human rights and information-exchange network in the favelas of Complexo de Alemão and Penha in Rio de Janeiro, at the Solidarity Between Nairobi and Rio online event on July 30 as part of the activities of the 5th Annual Black July. The event’s main theme was the end of apartheid, militarization, and racism, focusing on the importance of South-South connections in the fight against the militarization of the State. The livestreamed event was watched by over 3,000 people.

Separated by the Great Calunga* (the Atlantic Ocean), but connected by the pains of colonialism, the stories of the activists reveal not only the evils of colonialism that are still present today in daily life, but also an ongoing policy of death, in both countries, against poor and black people who live in favelas and peripheries, now even more accelerated by the Covid-19 crisis.

In Rio it is the “war on drugs,” in Kenya the “war on terrorism” and “war on crime.” According to the activists, these are different ways of justifying the same violent politics of a veiled social apartheid which exists in two colonized and highly segregated cities. The fight for life and for the end of State violence is transnational, and strategies of resistance aim to strengthen each other through being shared and conceived collectively. Especially, according to all of the participants in the online event, genocidal policies became explicit during the pandemic in both countries.

The World Bank estimates that 56% of Kenya’s urban population lives in favelas. Even though they are the majority, these people and their territories are criminalized every day by police forces who paint themselves as guardians of order and security. Kenya, like Brazil, is amongst the countries where the police kill the most, according to a report by MSJC.

“Our State is genocidal, it pays no attention to the poor who can’t wash their hands because there is no water nor ways of accessing… the minimum conditions to prevent the virus. So the poor have no one. The State wasn’t created by the poor. So we have to fight for our lives, even knowing that we don’t have ways of defending ourselves from this State,” said Wangui Kimari, co-founder and coordinator of research and participative action at MSJC. She added, “We want to strengthen the link with Brazil because we know that the police that kills in Kenya is the same that kills in Brazil. The conditions are the same.”

In April of this year, in Rio, there were 27.9% more police operations than in April of 2019, leaving a trail of 177 dead, according to a report by the Network of Public Security Observatories. The number of police killings was 43% higher than during the same period in 2019, according to the Institute of Public Security.

In April of this year, in Rio, there were 27.9% more police operations than in April of 2019, leaving a trail of 177 dead, according to a report by the Network of Public Security Observatories. The number of police killings was 43% higher than during the same period in 2019, according to the Institute of Public Security.

Lana de Souza, a journalist and co-founder of the Straight Talk Collective, established in 2014—which initially had not intended to produce narratives focused on harm reduction and the war on drugs—explained that the issue of violence pierces through “our bodies, our activities, our lives.” The collective gained visibility with this work, but has been trying to work in a more pedagogic way within this debate and is acting to balance their agenda toward the production of cultural and proposal-based narratives about Complexo do Alemão.

But with the pandemic, police repression has intensified, reinforcing the importance of strengthening the bridges of solidarity across nations and across the Global South in confronting State violence.

“We had to literally stop and drop baskets of basic foodstuffs on the ground to pick up bodies, because the situation here is that, inside our homes, we either were dying of the virus or from gunshots. This is why we had to risk contagion and take to the streets to protest,” Raull Santiago, another co-founder of the Straight Talk Collective, recounted. In this scenario, activists, community leaders, and communicators from the favelas and peripheries of Rio made the decision to take to the streets, even when faced with the risk of infection during the pandemic, to protest and shout that #FavelaLivesMatter and #BlackLivesMatter.

https://www.instagram.com/tv/CA3T8T_godZ/?utm_source=ig_embed

Currently, in Brazil, black people from the peripheries are condemned to die either from the virus or from gunshots. The reality is that in times of the pandemic, the only participation from the State was to enter into our communities to kill us. In the last two weeks, we had dozens of (reported) cases of young black people assassinated in the communities of Rio de Janeiro. Every 23 minutes, a young black man is killed in Brazil. The protest today in front of Guanabara Palace [the governor’s residence] comes with public calls against the genocide of black people in the country. NEXT SUNDAY THE STRUGGLE CONTINUES!!! ENOUGH!!! #enough #blacklivesmatter

“What we do most in Straight Talk is we principally try to stay alive to continue helping people inside our community,” Raull Santiago said.

In Rio de Janeiro, according to a report by Voz das Comunidades, 647 people were shot during the pandemic, of which 332 died and 315 were injured, since social isolation due to Covid-19 was first decreed. An inhabitant of Complexo de Alemão was shot in the leg inside her home on August 19. There was a police operation in the area even after a Supreme Court prohibition of such operations during the pandemic.

“When We Lose Fear, They Lose Power”

This is what activist Julie Wanjira shouted during this year’s Saba Saba March. Her cry was recorded as a police officer attempted to arrest the young woman during the protest. In one of the recorded videos, she asks why she is being arrested, and when the police officer asks why she is in the street, the activist replies: “Because you are killing us.” Constrained by the phone cameras, the State agent releases the young woman, who shouts: “When we lose fear, they lose power.”

https://www.instagram.com/p/CCWMeacHUIn/?utm_source=ig_embed

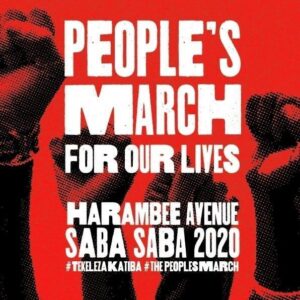

In Kenya, July 7 is known as Saba Saba Day due to large protests which took place in 1990, when many people died at the hands of the police and which brought about constitutional changes in the country, in the direction of a multiparty democracy. For the third consecutive year, on July 7, activists, community leaders and families of victims of state violence from 14 different favelas in Nairobi marched against this systemic violence carried out by the police.

This year, the Saba Saba March had the objective of presenting a list of demands to President Uhuru Kenyatta—the son of the country’s first president—including: the end of extrajudicial executions; the guarantee of article 43 in the Kenyan Constitution, which guarantees the right to health, housing, sanitation, food, water, social security, and education; the end of the militarization of public space; and the complete implementation of the Kenyan Constitution, known as Tekeleza Katiba.

This year, the Saba Saba March had the objective of presenting a list of demands to President Uhuru Kenyatta—the son of the country’s first president—including: the end of extrajudicial executions; the guarantee of article 43 in the Kenyan Constitution, which guarantees the right to health, housing, sanitation, food, water, social security, and education; the end of the militarization of public space; and the complete implementation of the Kenyan Constitution, known as Tekeleza Katiba.

According to activist Kimari, the march was interrupted by much police repression, tear gas, and the arrest of more than 60 people. The social justice centers of the informal settlements in Nairobi mobilized to get the activists out of the police stations and reaffirm their right to protest. “We inhaled a lot of tear gas and it was difficult, but for us this repression doesn’t do anything. It won’t prevent other demonstrations, because we’ve been facing the same problems for 30 years, so we’re going to demonstrate until we get what we need,” she declared.

For Santiago, meetings to connect struggles and resistance strategies are essential, not only between Rio and Nairobi, but across the entire world. This is important with activists in the United States and Europe, but principally between Africa and Latin America.

Activist Experiences: Strategies, Struggles and Resistances

MSJC was founded in 2014—at first with just seven people—to denounce how the police in Nairobi eliminated people and acted with violence in the favelas. With a participative action survey, MSJC was able to show that between 2013 and 2016, police were responsible for the deaths of at least 800 people in Kenya.

“The mothers of the victims would recount these deaths, but nobody paid attention. Even the NGOs didn’t want to know. They were confronted by the State’s official discourse. In Mathare [an informal settlement in Kenya], the police killed at least 50 people, but we all know it was many more, even though we could not prove it officially,” Kimari explained. For her, the only possible action is to keep fighting, even if the current generation knows that it will not yet be the generation that lives and reaps the fruits of this fight. “In our meetings, we always sing. There is one phrase which says ‘we will win.’ Because this is what it is: we know that we will win,” the activist declares.

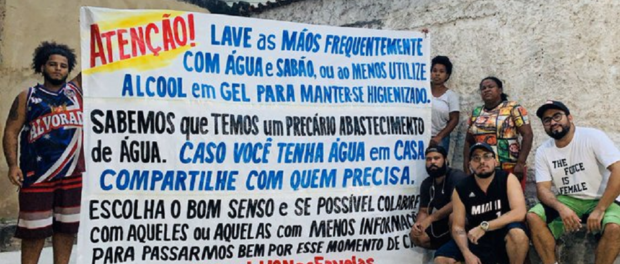

In Complexo do Alemão, beyond the production of counternarratives which denounce the situation of violence and the failure of the UPPs (Pacifying Police Units), the Straight Talk Collective has also been supporting families who are dealing with the crisis caused by the coronavirus pandemic. According to a survey carried out during the pandemic, the community made up of 16 favelas has 180,000 inhabitants and around 45,000 families.

In Complexo do Alemão, beyond the production of counternarratives which denounce the situation of violence and the failure of the UPPs (Pacifying Police Units), the Straight Talk Collective has also been supporting families who are dealing with the crisis caused by the coronavirus pandemic. According to a survey carried out during the pandemic, the community made up of 16 favelas has 180,000 inhabitants and around 45,000 families.

“It is not our responsibility to do what we’ve set out to do. But the pandemic was there, and when we look at the numbers, we can see the impact that we were able to reach inside a favela like Complexo do Alemão,” de Souza said.

The fight against Covid-19 in Complexo do Alemão is carried out by the Alemão Crisis Center formed by the Straight Talk Collective, news site Voz das Comunidades, and Women in Action (Mulheres em Ação). With 32 volunteers, the group has already managed to reach 13,000 families.

“We do this work because we understand the importance of our people [residents of the community] having a minimum of dignity at this time. We know that our options are to die from a gunshot or from the virus. What we’re doing is to fight so that we don’t die. We act according to ‘us for us,’ which happens in practice, in our daily lives, all of the time,” de Souza said.

Solidarity from Nairobi to Rio is a reality between favelas and from black and poor people to other black and poor people, in the activists’ opinions. According to them, the reality of favelas and peripheries does not have an impact on society, as it is this system of inequality and racism forged by colonialism that still exists in people’s minds and that maintains the privileges of those who do not live in these territories.

“Society is comfortable because violence happens inside favelas and their lives follow their normal courses. People outside of the favelas live another social reality. Here, when there is a shortage of water, people share their water with their neighbor. This would never occur to someone who doesn’t live our reality, for example, as a form of prevention against Covid-19,” de Souza said.

Kimari also believes that the lack of unity and public outrage about State violence in Kenya is part of the colonial imposition forged in the minds of the population. Divisions between ethnicities—which were imposed and incentivized during colonialism—impede and challenge unity around fighting and resistance.

Watch the Livestreamed Event Here:

*Calunga, amongst the Bantu people, means a spiritual entity which manifests itself as a force of nature. It is especially associated with the sea, death, or hell. Black enslaved populations who were brought to Brazil called the Atlantic Ocean the Great or the Green Calunga, because not only did many encounter hell or death on the slave ships, but also for many, the crossing of the Atlantic represented the end of their lives: physical and spiritual.