This is our latest article on Covid-19 and its impacts on the favelas and the second of a two-part report analyzing the inequality in the Covid-19 case fatality rate in two different neighborhoods of Rio de Janeiro’s West Zone, Barra da Tijuca and Campo Grande. The article was written by members of the West Zone Solidarity Web.* For Part I, click here.

This second installment analyzes a series of data—which allows for a reading of other structural inequalities—and a concealment of other statistics, which prevents the general population from having a clear view of its local reality in the face of the pandemic.

Post Code 23000

Let’s take a closer look. Let’s open up the box of statistics and understand the social and geographic distance which separates the two West Zone neighborhoods previously mentioned in Part I: Campo Grande and Barra da Tijuca. Different in landscape and with an abyss in racial inequalities—with figures suppressed from prime time media analyses—they are not different from the image of Brazil as a whole. According to Jorge Abrahão, coordinator-general of the Sustainable Cities Institute, while, in general, Covid-19 risk factors are linked to advanced age and comorbidities, in Brazil, the principal risk factor is a person’s post code (CEP), which demonstrates the matrix of inequities and the triangulation of data that spacializes social oppression.

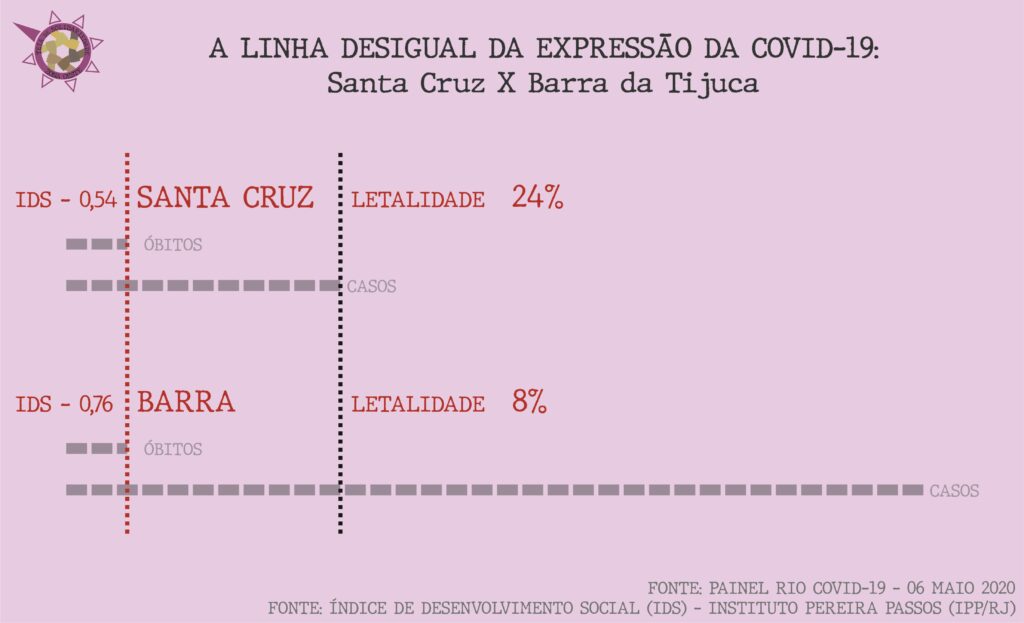

In the following diagram, we present the expression of this observation on the Covid-19 case fatality rate in the neighborhoods upon which our analysis is centered, Santa Cruz (which is next to Campo Grande) and Barra da Tijuca. What can be seen is the significant superiority and velocity of the advance of figures registered in the comparison between the two territories, and how the post code, for Covid-19 in the West Zone, is lethal.

Campo Grande is a microcosm of Brazil. Campo Grande is less than 40km away from Barra da Tijuca, by winding roads. The journey takes 50 minutes by car. The usual route taken by workers—many in Campo Grande work in Barra da Tijuca—can take between one and a half to two hours, depending on the conditions upon entering a packed BRT bus at rush hour. They are domestic workers, doormen, gardeners, store clerks, and a group of service providers who move between the poor neighborhood and the wealthy neighborhood—including during a pandemic, when there is no alternative.

It is the near-far in the geography of traffic. It is a gap in the indicators of these workers’ daily lives. In Barra da Tijuca, residents have an average per capita income of R$4,373 (US$794) per month. In Campo Grande, 54% of residents live on less than the minimum wage, and the average per capita income is R$737 (US$134). That is the difference between eating fruits and protein versus having little beyond the basics needed for survival. That means that many children in Campo Grande will try to forget their hunger with ultra-processed products flavored with sodium glutamate, which don’t even deserve to be called food. It is easy to deduce the innumerable implications for individual and community health.

It is the near-far in the geography of traffic. It is a gap in the indicators of these workers’ daily lives. In Barra da Tijuca, residents have an average per capita income of R$4,373 (US$794) per month. In Campo Grande, 54% of residents live on less than the minimum wage, and the average per capita income is R$737 (US$134). That is the difference between eating fruits and protein versus having little beyond the basics needed for survival. That means that many children in Campo Grande will try to forget their hunger with ultra-processed products flavored with sodium glutamate, which don’t even deserve to be called food. It is easy to deduce the innumerable implications for individual and community health.

Per capita income is just one of the indicators that make up the index of social development (IDS) calculated by the Rio city government’s Pereira Passos Institute (IPP). This index is composed of income and assessments of the adequacy of water provision, sewerage, trash collection, number of bathrooms per inhabitant, and the illiteracy rate among children and pre-adolescents aged ten to fourteen. In Barra da Tijuca, the IDS is 0.770. In Campo Grande, it is 0.572 (the index goes from zero to one, with one being the best rating).

Faced with this intersection of oppressions, it is easy to racialize the neighborhoods, even if they are not known to a majority of our readers. Data from Brazil’s census bureau IBGE, from 2010, show that Barra da Tijuca is the second whitest neighborhood in the city, with a population that is 87.59% white. Campo Grande’s population is 54.37% black and pardo (the Brazilian term for brown or mixed race).

The Highest Levels of Violence Against Women in Rio de Janeiro

Campo Grande also aggregates other vulnerabilities. According to the 2019 Women’s Brief from the Institute of Public Security (ISP), Campo Grande stands out as “the neighborhood with the highest number of reports of violence against women and registers of threats and intentional bodily harm against a female victim.” As the city of Rio registered a 50% increase in cases of domestic violence during the first month of the pandemic crisis in the country, we can deduce that in Campo Grande this number took on even bigger proportions. Another relevant statistic about the city, which certainly marks the poor and black neighborhoods of the West Zone, is the percentage of households headed by women, which has been growing in recent years, according to IBGE. This is yet another aggravating factor for the conditions of women in the low-income neighborhoods of the West Zone—like Campo Grande—confronted with the health crisis, as they already have some of the lowest incomes in the city, according to the IPP.

For the website Vermelho, columnist Mariana Branco analyzes a memo published by economists Laura Carvalho of the University of São Paulo (USP) and Luiza Nassif Pires from Bard College and doctor Laura de Lima Xavier of the Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary, in which the researchers worked on the relation between income, education, and risk of death from Covid-19, with basis in the National Health Survey (IBGE, 2010). We reproduce here part of the analysis related to access to medical treatment. They say:

With relation to access to health services, 94.9% of the poorest 20% say they do not have private health insurance, compared with 35.7% of the richest 20%. On top of that, the number of available beds in Intensive Care Units (ICU) is 1.04 beds per 10,000 inhabitants in the SUS [public health system], almost five times less than the 4.84 beds in the private health system. (BRANCO, 2020).

Part of the abyss between Barra da Tijuca and Campo Grande resides in the number of ICU beds and, consequently, ventilators. The purchasing power aspect is directly linked to the racial condition—we present it as a racial condition insofar as the process of racialization (what it is to be white or black, in a hierarchical relation) is a historical and political construct. Therefore, whites access high quality (preventative and emergency) healthcare, either through its purchase or through its guarantee by the State, as the majority of ICU beds are found in the neighborhoods of the South, North and Central Zones, rather than the West Zone of Rio. This condition is one of the expressions of necropolitics, which imposes upon black people a bigger risk of death, as a consequence of marginalization and vulnerability.

It is not by chance that these numbers presented here, also understood as disaggregated data, have not been the focus of those who hold public office. By keeping the focus on general averages across the city of Rio de Janeiro, as happens in the majority of Brazilian cities, they hide the chasm which separates the people with more or less risk of dying during the pandemic. That is why one of the basic conditions to demand right now is access to information, and also to reliable data that is open-source and can allow detailed analysis.

The reading of the reality exposed above illustrates how, through the choice to allocate resources in wealthy areas, there is a concealment of data about the advance of the illness in West Zone neighborhoods and a silencing of the social movements active in the region. The leaders of Rio de Janeiro are developing a silent conflagration against the black and poor population in this city, as the State takes actions which underreport the number of deaths, remove the race category from medical registers, and neglect the allocation of resources to the Social Assistance Reference Centers, providing evidence of the exercise of a morbid pattern of governance. To this pattern can be added the allocation of new field hospitals to areas far from the urban periphery and delays in payment of an emergency income stipend that should be urgent without valid justification, among other factors. These directly impact not only our living conditions, but also the continuity of lives.

The comprehension of this system of death, the responsibility for lives on the periphery, and the memory of family members and friends call for political action now! Our dead have a voice!

This article is the second installment of a two-part series analyzing the inequality in the Covid-19 case fatality rate between two neighborhoods in Rio’s West Zone: Barra da Tijuca and Campo Grande. For For Part I, click here.

*The West Zone Solidarity Web is a union of collectives and institutions in the West Zone that raise donations for some neighborhoods where their political performances take place. The Popular Collective of Women of the West Zone, the Institute of Human Formation and Popular Education (IFHEP), the Piracema Collective, the Caboclas Collective, Mulheres de Pedra, and institutions such as the Angelica Goulart Foundation and the Plano Popular das Vargens joined together to seek donations for the neighborhoods of Sepetiba, Santa Cruz, Campo Grande/Bosque dos Caboclos, Pedra de Guaratiba, and Vargem Grande.

Ana Alvarenga de Castro is an agronomist with a PhD in Gender and Agriculture at the Humboldt University of Berlin and a contributor to the West Zone Solidarity Web. She currently researches the dimensions of labor, land, and food in dispute in the context of socio-environmental conflicts in Latin America.

Camila Nobrega is a journalist and researcher raised in Vila Isabel and currently a doctoral student in Political Science at the Free University of Berlin. Camila works primarily with themes related to socio-environmental justice, Latin American feminisms, and the democratization of media, connecting journalism, activism, and research.

Caroline Santana is a doctoral student in Social Work at UFRJ, a Master in Urban and Regional Planning from IPPUR/UFRJ, a member of the Women’s Circle of the Rio de Janeiro Urban Agriculture Network, and an activist from the Group to Combat Racism in the Baixada Fluminense.

Marina Ribeiro is an educator, a social scientist with FIC-FEUC, an anti-racist researcher and activist, a member of the Popular Collective of Women of the West Zone and the Articulation Web for West Zone Solidarity, and a founder and general coordinator for the Institute of Human Formation and Popular Education (IFHEP).

Rosineide Freitas is born, raised, and still a resident of Campo Grande, a professor at UERJ, and member of the Rio de Janeiro Regional Board of ANDES-SN, Popular Collective of Women of the West Zone, State Forum of Black Women Rio de Janeiro and Collegiate of Civil Society of the Marielle Franco Permanent Dialogue Forum of ALERJ.

Silvia Baptista is a black woman of quilombola origin raised in Vargens, an educator, and a doctoral student in urban planning at IPPUR/UFRJ.

Infographics by Poliana Monteiro.