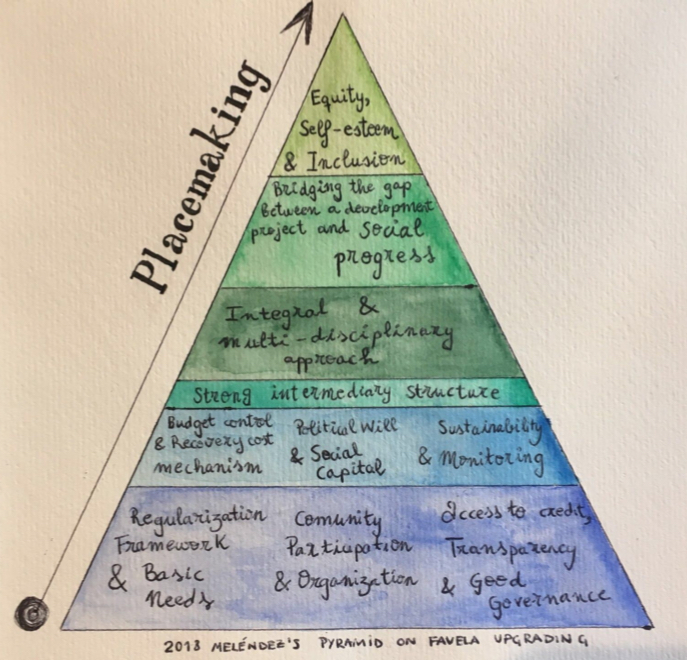

This is the fourth article in a six-part series on the application of Meléndez’s Pyramid for Favela Upgrading to the city of Rio de Janeiro and its favelas. This pyramidal concept was conceived by the author of this series as a proposed methodology to achieve more coherent and sustainable results in favela upgrading. Inspired by Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, the pyramid consists of ten blocks, each representing a group of indispensable elements. Essentially based on multidimensionality, interdependence, and simultaneity, the pyramid addresses the physical, political, economic, social, cultural, and psycho-emotional aspects of favelas.

This fourth article addresses the importance of political will, social capital, and sustainability. Read the full series here.

The ascension up the Pyramid for Favela Upgrading underscores the relevance of political will and social capital to achieve sustainable and context-based upgrading results. Closely intertwined, political will and social capital share a common basis in trust.

With regard to political will, a conducive political context is required for favela upgrading to really thrive. In order for this to materialize, public authorities and other city agents need to develop significant comprehension of favelas. To that end, frequent, equal-footing interactions between favela residents, other citizens, and the authorities are needed to generate an awareness about the past, present, and future of self-built neighborhoods and their contributions to the city. Moreover, communication based in the tenet of dignity for all is crucial to shift the logic underlying Rio’s urban processes and narratives of urban development discourse that propagate harm and exclusion. This process strengthens a citizen base that respects and dignifies the citizenry; equalizes through language, dialogue, and research; and promotes the socio-spatial-economic value of self-constructed urban areas—thus protecting them. The potential for such awareness throughout the Greater Rio area could increase political will for upgrading on favela residents’ terms.

Additionally, as mentioned in Part 3 of this series, institutional development and training for local government workers are a must, since local governments should: (1) listen to communities from a flexible and open standpoint; (2) build trust, compensating for decades of neglect by targeting funds and offering policy and technical support; (3) maintain beneficial policies regardless of changes in leadership; (4) stimulate economic and social partnerships between favelas and other areas of Rio (e.g., social enterprises, private investment, cultural events, and tourism); and, lastly, (5) adopt an active role in changing vicious urban dynamics (through language, media, research, socio-spatial economic policies, strategic and inclusive urbanism, and public spaces that foster casual encounters to fight stereotypes and stigma, among others).

Rio has rarely experienced periods of political will favoring favela upgrading. On the other hand, pushes for favela eradication come and go more frequently, based on economic swings, with times of high tourism, capital, and investment producing high pressure for removals. Among the principal arguments used today is the classification of favelas as “areas of risk”—according to city government agency Geo-Rio, that claims many hillside favelas (typically in Rio’s highest income areas) run the risk of falling in a landslide. These claims are regularly contested by independent engineers and technical experts. Research shows that, in a number of cases, there are double standards about this designation of risk when it comes to high-income developments, suggesting that the designation is driven by market forces rather than by the goal of protecting the environment or human life. Alternatively, a more positive long-term approach for Rio’s economy and society would be to address the deep-rooted issues underlying the formation of favelas and to expand the scope and audience of the opportunities, services, rights and duties offered by the city—ultimately strengthening the city for all.

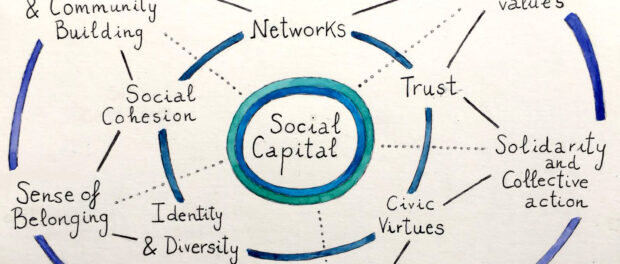

For its part, the concept of “social capital” encompasses elements that enable a social group to function effectively and inclusively: civic virtue, social cohesion, solidarity, collective action, capacity- and community-building. Partly due to favelas’ urban features (low-rise, high-density development, walkability, organic architecture, and social networks), social capital is inherent and invaluable to residents’ daily lives.

Historically, favelas relied on cooperation to survive. Their collaborative networks can produce immense social capital, a key survival strategy to cope with government neglect. The strength and cohesion produced by these networks have also allowed some favelas to fight eviction. Social capital and favela self-organization ultimately act as opposing forces to the losses provoked by government neglect and eviction.

The richness of social capital in Rio’s favelas is embodied by inspiring community organizing efforts that yield a chain of impacts. Compensating for public neglect, residents have organized waste management, recycling and sewerage systems, income generation, mental health and women’s empowerment networks, early childhood education, support for the elderly, free college exam prep courses, art and culture, graffiti, sports, community kitchens, food sovereignty projects, knowledge-shares, and innovative campaigns to fight the Covid-19 crisis, among many other initiatives. Reflected in Catalytic Communities’ (CatComm)* 2012 Favela as a Sustainable Model film, Rio’s favelas are generating interconnected and holistic practices for social capital, autonomous local development, and sustainability.

Given its demonstrated contributions to the well-being of residents, Rio’s authorities should leverage favelas’ existing social capital and cooperative nature to promote socio-spatial dignity. Attaching more importance to social capital is crucial to start considering people and their involvement as the end itself rather than just a means for favela upgrading. With political will and social capital in the equation, upgrading outcomes will be autonomous and sustainable.

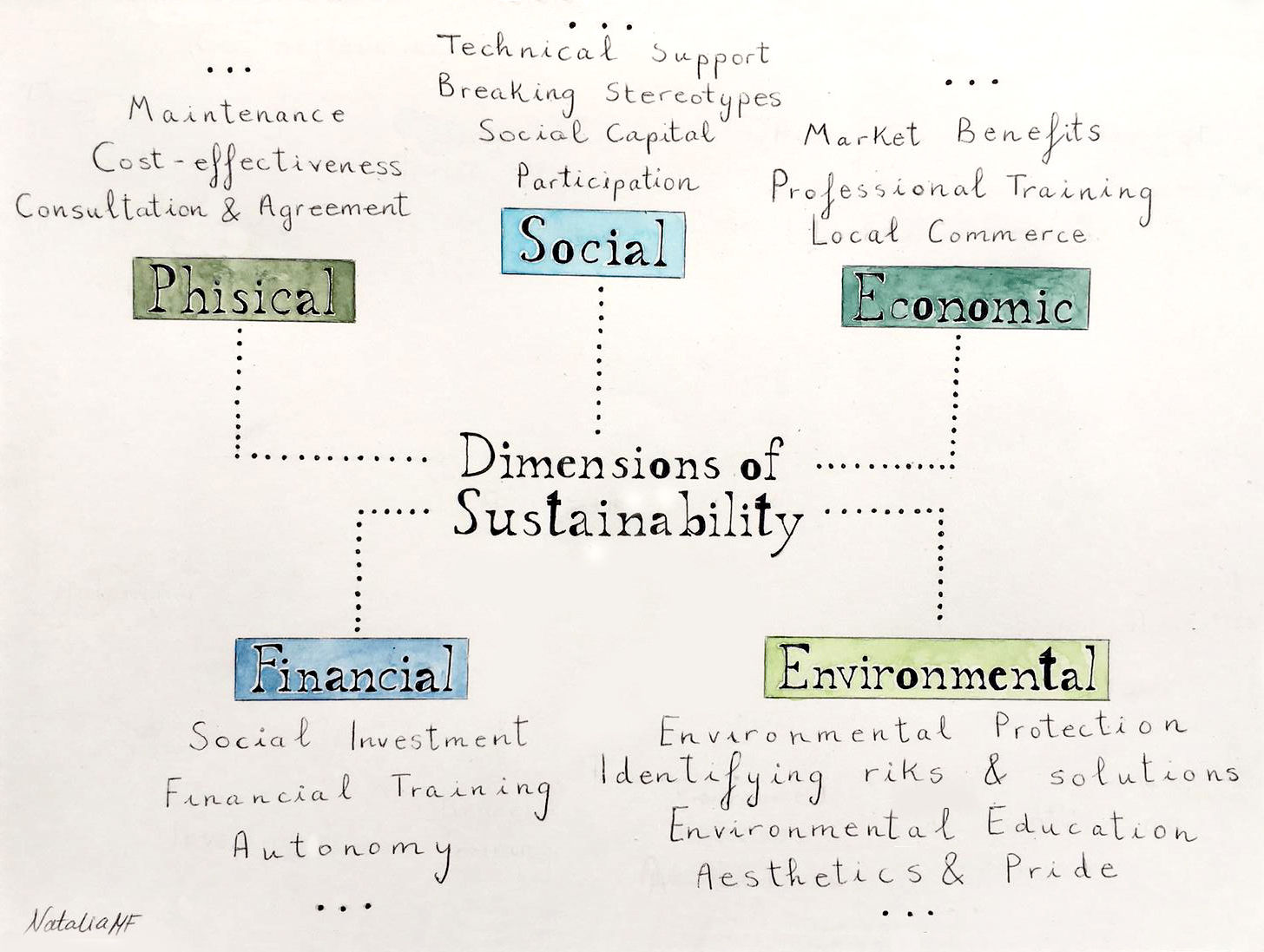

The last block of the second level of the Pyramid is constituted by sustainability and monitoring. As reported by Diana Mitlin of the International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED) in London, when observed years after completion, many upgrades of informal settlements the world over are found to be in decay. Sustainability is thus an essential challenge. A program is said to be sustainable when it is regularly maintained and generates ongoing improvements, unleashing long-term social development processes. And, to be sustainable, favela upgrading must originate in and be driven by communities, addressing at least five dimensions: physical, social, economic, financial and environmental. It is paramount that sustainability be approached as a social process where humans and nature coalesce.

Along these lines, CatC0mm mapped over 100 community projects in Rio in 2017, in preparation to launch the Sustainable Favela Network, “to generate knowledge exchanges, capacity-building, partnerships, and resources.” Each of these projects, along with many others who have joined since, epitomize the uniqueness and vigor of favelas as urban and social alternatives for Rio and beyond. Addressing sustainability in a multidimensional manner, some of these projects include: the Eco-Park in Vidigal, the revolutionary solar irrigation system in Santa Marta, and Devas’ women artisans, among many others. Contrary to the dominant discourse that favelas are harmful to the environment, many favelas contribute to environmental sustainability.

For sustainable achievements not to run into sand, monitoring and maintenance are essential. These should be planned for before implementation, in order to allow stakeholders to prepare. Early planning of monitoring and maintenance can produce better information records and improved monitoring results. Roles and pathways for accountability should be clearly stated.

When combined, political will, social capital, and sustainability can allow for a truly effective upgrading paradigm for favelas. The previously mentioned favela projects and many others profiled by RioOnWatch show a holistic and multidimensional outlook toward sustainability in favelas which offers invaluable lessons and opportunities—usually obscured by the formal-informal dichotomy.

This is the fourth article in a six-part series.

Natalia Meléndez Fuentes is an MSc candidate in Building and Urban Design in Development at the Bartlett Development Planning Unit at University College London. Her research looks at urban informality learnings, the psycho-emotional elements of favelas and favela upgrading, mainly in Latin America, and how to bring these to the fore.

*Catalytic Communities (CatComm) is the NGO that publishes RioOnWatch.