“Why toil in the country, in the city?

The machine will do it for us.

Why think, imagine?

The machine will do it for us.

Why write a poem?

The machine will do it for us.

Why climb Jacob’s ladder?

The machine will do it for us.

Oh machine, pray for us.”

Litany, by Cassiano Ricardo

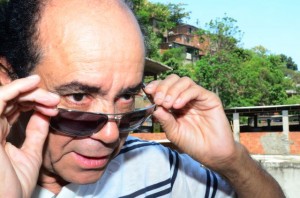

With dramatic intonation, Seu Rodrigues recites a few verses of this poem. Not many photographers pay tribute to their camera during an interview. But 58-year old Manoel Rodrigues Moura, photographer and resident of the Complexo do Alemão community, has a special reason to do so. Seven years ago he partially lost his vision, perhaps due to diabetes. “Today the camera sees for me. I am still able to show it what I want it to do, and the camera takes it from there. I’m grateful that even with this visual disability I can still work among great photographers,” he says.

In front of the lens lies Alemão, the community he has chosen to live in and to represent in his photographs. Behind the lens lives a story that began in the interior of the state of Minas Gerais. Seu Rodrigues lived there until 1979, when at 25 he decided to move to Rio de Janeiro and stay with friends at their house in the Complexo do Alemão. “I started out living in extreme poverty, but the word favela didn’t exist. My first job was as a servant,” he remembers.

Photography came into his life over the radio, when he heard an advertisement for a correspondence course and decided to enroll. “That opened a tremendous horizon to me. I learned some of the tricks of photography. From there I had to keep working to get into it, but that was the kickoff.” And it was. When Seu Rodrigues left his job as a servant, he used his workers’ compensation money to buy a camera. Before long he was taking pictures of first communions, debutante parties, baptisms and weddings. Since then he has made his living from photography.

Photography came into his life over the radio, when he heard an advertisement for a correspondence course and decided to enroll. “That opened a tremendous horizon to me. I learned some of the tricks of photography. From there I had to keep working to get into it, but that was the kickoff.” And it was. When Seu Rodrigues left his job as a servant, he used his workers’ compensation money to buy a camera. Before long he was taking pictures of first communions, debutante parties, baptisms and weddings. Since then he has made his living from photography.

Viva Favela and the journalist’s eye

Seu Rodrigues got started in journalism through Viva Favela, a project of the NGO Viva Rio. Viva Favela was created in 2001 as an Internet journalism portal whose content was produced by community correspondents living in favelas and on the outskirts of Rio. That year, the project began to select photographers from various neighborhoods in Rio. “I grabbed a piece of paper, wrote down my name and I.D. number, and attached some pictures. Two weeks later, they called me,” he says.

The experience with Viva Favela gave a new face to Rodrigues Moura’s photography. Weddings and baptisms began to share space with daily life in the favela, social problems, and residents’ stories. He recorded important events in the history of Complexo do Alemão, such as the flood of December 2001; the occupation of an abandoned factory in 2004, and the army occupation of the favela in 2010.

But he doesn’t portray the favela as a place of only tragedy and violence. Through Rodrigues Moura’s lens, Complexo do Alemão has sports, parties, creativity, workers, mothers, children – an immense universe that the mainstream media has never managed to understand and disseminate. “To display the community to the world is like making a hole in the wall of prejudice, so that, quietly, society begins to see it,” says Seu Rodrigues, who has taken pictures of bike trails, street theater, and the famous rooftop sunbathing.

His work in Rio de Janeiro’s favelas, particularly in Alemão, has led to his participation in various exhibitions, such as “Inside the Favela” in 2003; “Rio with Open Eyes” and “Eco-favela” in 2005; and “I live in the Favela” in 2006. Also in 2006 he studied at the Maré People’s School of Photography. Seu Rodrigues has had photos published in the newspapers O Globo, O Dia, and Extra, and in the magazines Onda Jovem and La Rampa. Of all his published work, he is most proud of the photo on exhibit in the gallery of modern art in Zurich, Switzerland.

The community through his eyes

Manoel Rodrigues Moura’s story is often indistinguishable from the story of Alemão, a network of favelas in Rio’s North Zone that he describes like no one else. “The Complexo do Alemão is in a beautiful location, nestled among the Misericórdia Mountains. From some viewpoints here you can see almost all of Rio de Janeiro,” he says.

Manoel Rodrigues Moura’s story is often indistinguishable from the story of Alemão, a network of favelas in Rio’s North Zone that he describes like no one else. “The Complexo do Alemão is in a beautiful location, nestled among the Misericórdia Mountains. From some viewpoints here you can see almost all of Rio de Janeiro,” he says.

Today, tourists and residents of Rio come to contemplate the beauty of the communities in the Misericórdia Mountains from the cable car. But it wasn’t always this way. Before the installation of the Pacifying Police Units (UPP) in Alemão, the media and broader society looked down on the community. “A while ago, if I went to the Central Station and told people I lived in the Complexo do Alemão, everyone would think I must be a criminal. Today, when I say I’m from the Complexo do Alemão, tons of people want to know what’s going on here,” explains Seu Rodrigues.

However, he says, Alemão is not yet the paradise that the government and media make it out to be, and residents are still deprived of certain rights. “As far as people displaying their weapons, things have changed a lot. But socially, nothing has changed. There is not a single school or university here. To get transportation, you have to leave the favela. All we have here is alternative transportation. We don’t have basic sanitation. You see polluted ditches everywhere,” he says. Pacified or not, Alemão continues to be recorded by the lens of Seu Rodrigues, who casually downplayed his vision problem for this story.

In his 1964 poem “Litany,” Cassiano Ricardo described the transformations that technology has caused in our daily lives. In Manoel Rodrigues Moura’s life, the camera represents good and profound changes. He offers a speech of gratitude to his camera: “If it weren’t for this camera, I would never get to go to the places I go, I would never be invited to participate in the things I’m invited to. If it weren’t for this camera I wouldn’t be known by anyone. I give thanks for this camera; it’s everything.”